Via Ta-Nehisi Coates, Andrew Wheeler’s smart take on DC Comics’ conceptual failures in its “New 52” relaunch of its intellectual property. (For another good analysis, see Laura Hudson’s essay at Comics Alliance.)

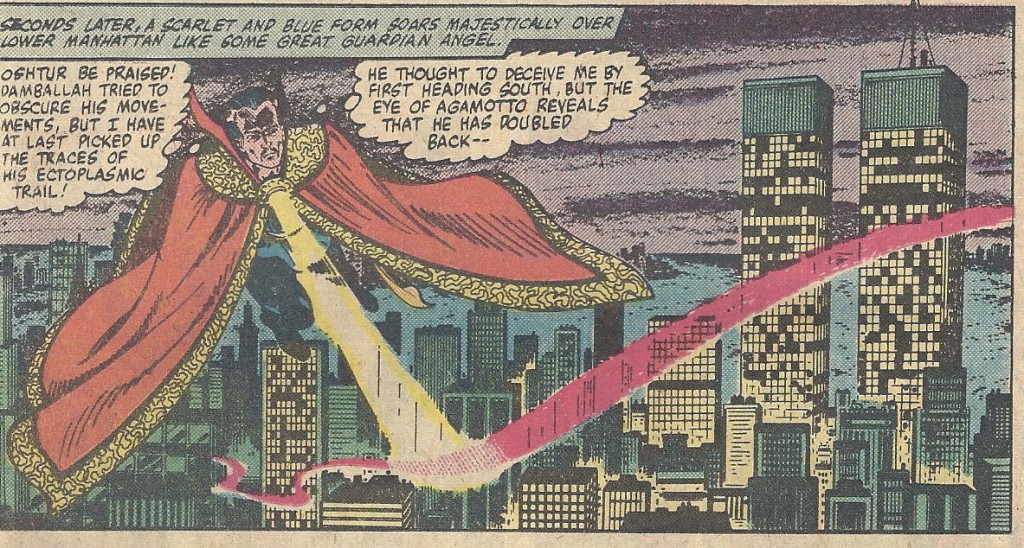

For folks who don’t follow the comics, well, for one, this is probably not a good time to start. Especially if you’re anybody but a particular kind of male reader looking to be pandered to (and peculiarly willing to pay $2.99 per pander when you can get all the pandering you like for free online). I’m not going to restate at length what Wheeler and Hudson say perfectly well. The problem is not sexy characters, nor characters having sex. It’s poorly written characters where the poorness of the writing involves in particular an unimaginative reliance on stereotypical characterizations and situations that are narrowcasted to a very particular imagined audience. Even that might not be an issue if the reboot was 52 comics narrowcasted to 52 different possible audiences, but it’s not. There are really only two audiences in sight: the dwindling numbers of existing comics fans, who enjoy weird boutique rearrangements of genres, tropes and references like All-Star Western or Demon Knights (I’m in this audience) and a very small audience of men who seek the aforementioned pandering.

I’ve talked before about the problems of cultural properties that are trapped in a dead end matrix of medium, audience, themes, expectations. There are ways out of that situation, but usually the people that got into the trap can’t see them. The wider thing that interests me about the blindness of DC executives in this case is how they’re connected to similar perceptions in other contexts that the lack of a particular kind of male audience is somehow the most important lack to resolve. Disney executives, for example, have been fretting for a while about how to draw boy viewers to their television programming, and about the perceived danger of becoming seen as “female”.

Behind that fear I think you can glimpse just how powerfully maleness continues to define “normal” and femaleness “difference”. If you’re a medium or a program understood as being for women, in the eyes of many cultural producers, there is no way back to being for people. For cultural producers who are self-consciously seeking male audiences, on the other hand, the only time you might believe that move will make men your only audience is in parodistic excess like Comedy Central’s The Man Show. Somehow DC Comics’ current executives can believe that if they play to a very particular male subculture, they will catch other audiences along the way, or at the very least not permanently change the character or nature of their intellectual properties so as to forever lose other audiences. It seem somewhat obvious that they are much more afraid of presentations that play to other audiences in that respect. Disney executives somehow fear that if it’s only tween girls turning in, it can only ever be tween girls.

The interesting shadow question that hovers around these kinds of anxieties is “where are those lost men going to“? DC’s shadow question seems to be, if comics are losing the male audiences who would have read Gen 13 primarily to see Fairchild in risque poses and semi-undress in 1995, where are they now and how can we find them? They’re signalling in the night sky with Catwoman’s breasts the same way Commissioner Gordon uses the Bat-Signal. And even if I think it’s commercially self-destructive and aesthetically unpleasant to pine for and seek that particular set of missing men, the question itself is kind of interesting. Where are those men going to? Were they ever there in the first place, and were they there for the reasons that cultural executives presume that they were? When I see some of a few of the angry pro-Red Hood and the Outlaws fans surface in the comment threads at comics sites to offer semi-literate denunciations of killjoy feminazis, it’s a bit like seeing one of the Great Old Ones stick a tentacle through an eldritch portal outside of Dunwich: a weird, maddening visit from a remote dimension. But once upon a time, those commenters were as thick on the ground in fannish communities as antelope on the Serengeti.

Where are those men? Maybe they really did not ever exist, maybe the stereotyped desires that both I and DC executives are projecting on to them (for our divergent reasons) never existed. Maybe they grew up. Maybe subcultures of male mischief and misanthropy blossomed into a richer, stranger, more distributed range of subcultures and genres.

Where are the boys that Disney is looking for? Watching something else? Playing video games? Watching nothing at all? Disney’s certainly right that they’re sociologically real: there are as many boys as girls but they’re not watching Demi Lovato and Selena Gomez and Miley Cyrus as much. Are they at Disney XD and Phineas and Ferb yet, as much as Disney would like? I’m guessing not. Or if they are, they’re not doing all the subsidiary consumption that drives the big profits, either of stuff connected to programs or stuff advertised on programs.

Tracking the migrations or absences of men from audiences, and figuring out how to call them to the table isn’t just a problem that wakes up comic book editors and television executives in the middle of the night. It’s becoming an issue for selective higher education as well: fewer male applicants, and a much narrower range of male interest in opportunities within higher education. So I don’t mean to entirely snark at someone else’s expense. Men aren’t vanishing from social structure: so why and when are they disappearing from spaces where their volition and desires were an important driver in the past? (And if they are, for whatever reason, should anyone care?)