I’ve been trying to think of what to say about the “reboot” of DC Comics’ line of published titles that has generated so much talk among comics bloggers and commenters. On one level, purely as a consumer, I’m just kind of annoyed by it. I don’t enjoy very many ongoing titles by the dominant publishers any more, but this move is going to disrupt several of the few left that I do like and will actively buy on a monthly basis because I don’t think they’ll be available later in other form. (Unless it’s an obscure but interesting run that’s not likely to be republished as a trade paperback or in digital form, it’s not going to motivate me to head to the comics shop.)

In that respect, I’m a fairly typical comics reader. I’m part of an aging population that skews male, has a long history of reading comic books, somewhat jaded about the genre and form but is also motivated to some extent by the not-yet-exhausted pleasures of nostalgia. As many of the folks who’ve weighed in about DC’s new line have observed, readers like me are the problem in two respects. First, there are fewer and fewer of us willing to pay out to read the still extensive monthly output of the major publishers. The long tail of traditional comics publishing gets longer and longer and smaller and smaller with each passing month, even as the intellectual properties themselves have become ever-more successful mainstream cultural artifacts. But the work which still opens wallets among the dwindling audience is precisely the antithesis of the kind of work that might attract new readers.

To avoid exacerbating that problem, I should explain what’s going on. Because once I get past my immediate irritation about DC’s gambit, I think there’s a deeper cultural problem here that affects much more than just the publishing of superhero comics. DC Comics, which is owned by Warner Brothers, has announced that at the end of August, all of their current monthly comics will come to an end and a completely new line-up of 52 titles will begin coming out with simultaneous digital and brick-and-mortar editions. On paper, that sounds like a bold move, a chance to begin anew with versions of the established characters that might appeal to new audiences.

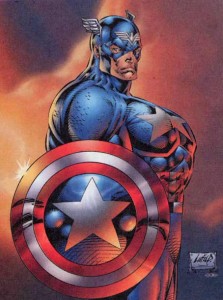

Expert comic-book Kremlinologists, however, have run over the announced list of titles, creative teams and the visual redesign of characters and found little reason to think that this initiative is that kind of rethink. Most of the titles conceptually have the same continuity-porn self-referentiality that current versions do. The writers are the same writers who’ve written numerous previous titles to appeal to a small fraction of the shrinking audience. The redesigns harken back to the worst creative excesses of the 1990s, an era where superhero comics were mostly driven by collector speculation and by wretched visual tropes like pouches, huge shoulderpads, guns the size of the Empire State Building and anatomy like these two drawings:

However, I don’t think this is just about making a bold move on paper and then not having the guts to follow through on its implications. There’s a structural problem here with the management of what Jason Craft called “fiction networks”, or “proprietary, persistent, large-

scale popular fictions” in his excellent 2004 dissertation.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that shared-universe superhero comics in their published serial form are struggling with a crisis of viability at the same cultural moment that television soap operas are fighting for their life. They have the same problem of a dwindling audience whose intense loyalty to long-established genre norms both threatens and sustains what life is left in the form. Serial drama is expensive to make, even with the numerous cost-cutting strategies that daytime soaps have employed over the years. But it’s not just about the costs.

If you look at the big picture, serial drama is in pretty good shape. Sure, reality shows have pushed most serial drama off of the broadcast networks, but on basic and extended cable, some of the best examples of the form ever are airing. Part of the problem is that they tend to show how deep the cul-de-sac really is for daytime soaps, how much their own traditions and audience expectations thereof have become a serious limit. HBO’s serial dramas show what happens if soap operas could discard limits on sex, violence and profanity while being superbly written and acted: if you squint properly, you can see a kin relationship between The Sopranos and General Hospital. Other cable niches permit other variations as structural premises.

That’s the problem with long-running “network fictions” like the daytime soaps or superhero comics: they tend to revert to a baseline after exciting variations or explorations because the long-tail core audience expects, perhaps demands, such reversion. Passions could have magic, witches, surrealism, violence, but it couldn’t keep it going forever. Grant Morrison can shake up the status quo of the X-Men or Batman, but the company and the readers are going to eventually want to curl up safely with a reverted version.

What’s notable here, particularly in terms of Craft’s dissertation analysis, is that when these properties leap out of the media creche that contains their eternal reversionary impulses, they often can shed most of the accumulated crud that prevents them from moving on or evolving.

For example, I’ve been re-reading old Lee/Kirby Thor comics recently. There’s no way you want to be a storyteller today who has to regard those as stories which happened to the character of Thor and require continuing reference as part of the fictional history of the contemporary character. Sure, some elements are wonderful, the tone is evocative, but Thor’s girlfriend Jane Foster is a ridiculous misogynstic caricature and his father Odin is unambiguously mentally ill. You could find inspiration in the early comics, and the reasonably decent film did, but any ongoing publication should continually reboot and rethink the character. The thing to do is find great storytellers and let them tell interesting stories about Thor, a godlike superhero, a powerful alien from another planet, a fish out of water stuck on Earth, a character of uncertain sanity: all versions have had some useful life in the comics here and there. That’s what you’re shooting for, and what you want to support. The other important thing? Cut way down on the intertextuality, the crossovers, the asterixes from assistant editors about the last time Thor met the Absorbing Man.

Whether it’s soaps or comics or other network fictions, what happens when they leap from their place of cultural birth is that a new creator has to take a hard look at the primal story underneath. What’s Green Lantern’s story? Well, he’s a guy who finds a magic ring that can do anything. Ok, ask yourself what usually happens in those kinds of stories in most human culture. “Joins a police force of aliens who fight fear demons” is assuredly NOT high on the list. There are precedents for “human gets involved in a fight far bigger than himself and learns to deal with it” (E.E. Smith’s Lensman series most notably) but it’s not the same story as “finds a magic ring that can do anything”. The thing is, the two stories in the history of the character Green Lantern are combined partly by the accidents of themes that post-Comics Code superhero stories would support, not because they’re logically partners. The Green Lantern film did as poorly as it did partly because it couldn’t decide how to resolve out the weird conflation of not-particularly-congruent stories and escape the history of the genre and medium.

The other important thing? Cut way down on the intertextuality, the crossovers, the asterixes from assistant editors about the last time Thor met the Absorbing Man.

Do you really think this is the case? I’m not defending intertextuality, cross-overs, world-creation and maintenance in general as something necessary to good story telling, but I’m not sure it’s necessarily always a problem either. Perhaps the problem is simply how it becomes addicting, a kind of fan-bait that can’t be left alone, and so it’s better to avoid it entirely? I could accept that. But I’m not sure how Law & Order was necessarily weakened by placing it in the same universe as Homicide, or how any of the “next generation” Star Trek series were hurt in terms of their ability to tell good stories solely because there were multiple series talking about the Federation, making use of similar sets of referents. (We talked before about the problems, as well as the possibilities opened up by, the Star Trek reboot, and I can see the argument that, by the time you’d gone through decades of story-telling and reruns and improvements in special effects technology and general audience expectations, that locking Star Trek into its own developed mythology and referents would be counter-productive. But I’m curious if you’re making an argument that, if you are telling stories about Picard, you really in principle make certain that Sisko never comes up.)

Those two images are hilarious.

I’m a fan of Doonesbury. That comic strip shows a different way to make a rich story world where the characters are updated to stay current over decades. There’s a range of techniques, and I hope creative people think big.