II. Algorithmic Culture: Code and Agency

New media theorists and digital humanists, most prominently Alexander Galloway, have been writing over the last decade about “algorithmic culture”, about practices, interpretations and readings that arise within and around algorithmic media. Galloway often tries to chart a path out of the typical binaries of bad or good interfaces and implementations, away from the debate over whether algorithms and AI are a boot stamping on the human face forever. With less theoretical savvy and detail, I’m going to try to do the same in this analysis of 500px and Flickr. In particular, I’m going to try and work within the approach described very well in Chapter Four of N. Katherine Hayles’ new book How We Think, in which she charts “a complex syncopation between conscious and unconscious perceptions for humans and the integration of surface displays and algorithmic procedures for machines”. (Hayles, How We Think, p. 13) Along the way, I’m going to compare these sites expressly to massively-multiplayer games like World of Warcraft, to show how similar the design imaginaries and their attendant contradictions and crises are across a broad range of algorithmic media.

How It Works

500px is the most interesting of the two sites in this sense, in part because of attention to interface and audience I described in my first post in this series. Flickr’s rating system is fairly rudimentary and linear: users can favorite a picture, they can comment on a picture, and the total views of pictures are tracked. An algorithm that relates favors, comments and views ranks photos as more or less “interesting”, and in turn, “interestingness” is used to identify which pictures should be highlighted in the area of the site called Explore.

500px uses somewhat similar mechanics to move images between filters called “Fresh”, “Upcoming” and “Popular”, and to move them within those designations. They have added two ways to rank: a “like” button, also known as a “vote”, and a “favorite” button, which filters the image into a user’s personal archive. In addition, as at Flickr, you can choose to follow another user, but at 500px, the activity of the users you follow fills the filter called “Flow”–you see not only what they post but also what they have voted and favored. 500px users can also comment on an image.

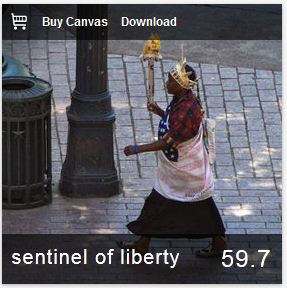

At 500px, votes and favors influence a measure called Pulse, which is visible on thumbnails from a mouseover. Pulse is a highly engineered algorithim: it leaps quickly above 50 from one combination of a favor plus a vote (you learn quickly that this is what it means to have a 59.7 Pulse) and then accumulates more and more slowly as it approaches 90 (out of 100), making a move past 99.4 exceedingly difficult. A photo moves from Fresh to Upcoming to Popular as it climbs in Pulse. Once it reaches its peak rating, it begins to slowly decline in Pulse at a steady temporal pace until it hits 50, reverting again to Fresh in time. (If an image is ever selected as an Editors’ Choice, it retains that filter for the rest of its time on the site.) An image can continue to garner favors and votes after its Pulse starts ebbing, but this will at best slow its recursion to the average.

However, photographers also have a measure that cumulates in a linear manner, called Affection. This does not decline over time: it simply gets bigger and bigger as the user’s images gain favor and votes. (It does not move from gaining or losing followers.) It only goes down if an image is disliked or if the user deletes an image that had likes and favors on it. A high Affection entitles you to dislike images: most users do not have access to the option.

Even if the site designers were secretive about the intent behind this design (they’re not) it would be fairly easy to see the intent. If photographs accumulated Pulse in a linear fashion, the Popular filter would be a largely static register of the most popular images ever uploaded to the site. (You can get a version of this, in some ways, by looking at which images are bestsellers in the Market tab.) This would be visually dull, and more importantly, discourage any new entrants to the site hoping to get attention for their own images (or even discourage established users with high Affection from hoping that newer images of their own might ever make it to the top of Popular). Pulse imposes the rule of time on what would otherwise be a photographic oligarchy. Virtually every competitive mechanism in massively-multiplayer games like World of Warcraft have been subjected to similar mechanics of decay and reversion, for the same reason: advantages which accumulate in a linear fashion and which are never disrupted or restarted quickly kill competition, deter new participation, and make the game dull for everyone, even the winners.

The Playing Out of Algorithmic Design

The recognition of a mimesis to the recurrent crisis of capitalist accumulation has long been noted by critics and designers. What I’m concerned more with here is how the algorithmic regulation of competition plays out in lived practice. Several issues leap out right away. First, that there is a tension between Pulse and Affection that can’t be resolved by the algorithm or the design. Users (or in games, players) have to decide what matters most: the signs of long-term accumulation of reputation capital (some coded into the design, others outside of the frame of the site or software) or the more variable algorithmic signs of prowess and success. You could easily create a sort of super-stat that measured Affection against participant-time and number-of-photos to distinguish the photographer who has very high Affection density per image from the one who has high Affection simply from the sheer volume of images and length of time participating.

Pulse moves palpably to the will of the viewer: jumping it is a minigame in its own right, a nibble of cheese for the mouse that presses the levers. Affection moves glacially, as much a measure of how long a user has been contributing to 500px as it is of the variable acclaim of his or her peers. Affection sorts the site into a kind of social hierarchy, whereas a high Pulse for an individual image is notionally democratic, waiting for the one picture that sparks the hivemind.

The culture of practice doesn’t play out so neatly. Upon uploading a picture, it appears in Fresh. The volume of global uploads is such that any given image has around 5-15 seconds at almost any time of the day to stay on the first page of Fresh, and perhaps no more than 2-3 minutes in the first three or four pages. After that point, the only way for a user to discover that picture is either by looking at the photographer’s overall output or by seeing it in their Flow, where postings from followed users will appear. If a user is following a lot of photographers, then a new image will also move out of view quickly. In a user’s own profile, the default display is also temporal, meaning the first images that a new users posts will almost certainly not be seen by anyone unless they are extraordinarily spectacular or the user latter establishes sufficient reputation capital that other participants dig down into the archive and find images.

Moreover, the designers had to make a crucial adjustment from the outset: images that are tagged as having adult content have an algorithmically suppressed Pulse. The central justification for this move is that they are in aggregate the most likely images to be favored and voted and would dominate Popular if they were not adjusted, which would then change the entire presentation and purpose of the site and very likely drive away other photographers of all kinds. Which of course then creates an alternative motive for users to not tag their nudes or erotica as adult, which requires other users to notify the community managers, which creates a need for a penalty to users who fail to tag appropriately, which creates a possibility of malicious false notification or for that matter debates about whether an image is “really” a nude or erotica.

The conceptual point of both Pulse and Affection is otherwise strikingly different for different cultures of use within the site. A successful commercial photographer with an established business, like wedding photography, who is using 500px is likely seeing it first as a hosting service for a portfolio and a form of advertisement. Both Pulse and Affection are additional rewards for such a user, much as Yelp or Zagat reviews can help a restaurant, but they’re not necessary. A commercial photographer who is seeking work, say as a nature photographer or photojournalist, might cite Affection and Pulse as a part of a resume. And both measures also make it more likely that a photograph might be purchased in the site’s internal marketplace, which is good for both the photographer and the designers.

An amateur like myself with no real commercial aspirations sees Pulse in particular very differently. Pulse is like the digital camera itself: a rapid iterative feedback loop that teaches, a crowdsourced mode of instruction. But just as Ian Bogost has pointed out that games teach mostly about their own procedural content, so too does Pulse teach me as much about the algorithmic culture of 500px as it does about photography.

Here’s my highest Pulse image so far:

I don’t think it is in any sense my best photograph, but I understood why it attracted attention. The flower is a prominent subject even in a thumbnail, the bokeh in the background is attractively composed in relation to the foreground subject, and the pollen is crisply in focus and colorful.

Here’s my next highest:

Here I made a conscious decision to process the photograph for more attention. I like the composition and my focal point, but with ordinary pumpkin colors it seemed banal to me. So I desaturated the image some to create a different mood. Users at 500px seemed to respond very well to that choice.

Other experiments have taught me similar lessons. I took what I think is a fairly dull photo of a woodland path and dialed up the saturation of the green hues while processing it to dull the look of the path itself. I think it looks fairly lurid but it grabbed some attention when posted. Other photos that I like, on the other hand, languish deeper in my profile: posted too early in my participation, not grabby enough in a thumbnail, or so common in their composition and subject at the site that their technical merits hardly matter.

But working the algorithms of the site is also a game that has nothing to do with photography, and all users, whatever their reasons for uploading content, clearly play that game, perhaps in particular the most casual users who use the site for archiving personal photographs. Time of day, the random chance of how many photos are pouring into Fresh when there’s an upload (someone dumping thirty banal vacation shots of their buddies at a beachside bar can bury a sublime photo of a landscape by one of the site’s most prominent participants), juxtaposition of images, all of them matter and structure the dance of clicks and views and algorithmic workings.

More importantly, the social mechanisms that the site enables almost regretfully play a key role, as they do at Flickr. A vote for a picture carries no intrinsic social weight–and for that matter neither does a dislike, which is a persistent issue at the site. I can like a photo (or if I were sufficiently Affectionated, dislike one) without being unveiled to the owner of the image. If I favor the photo or follow the photographer, my user name is attached to the action. But users often want a photographer to know more immediately if they’ve voted or favorited an image. Hence a common comment is “V + F!!!” or something of the sort.

What this enables, not by algorithmic design, is an economy of reciprocity. And again, this is a common structure in algorithmic culture, wherever it is used to construct a competitive relation between objects and actions. In World of Warcraft or other MMOs that have measures like reputation or experience that can be gained by defeating other players, the mechanics immediately lend themselves to reciprocal conspiracy, in which players coordinate an industrialized, efficient exchange of consensual victory and defeat to raise each other’s scores far more rapidly than people who are playing “for real”, requiring in turn a mechanism that provides for diminishing returns for defeating the same person sequentially. Which in turn just leads to many players regarding the entire activity of play as a larger scale version of the same managed competition, shaved down to the most efficient and algorithmic procedures for accumulation, dumping off everything else as a kind of hermeneutical and philosophical dross.

Algorithmic design approaches people like a Turing Test in reverse, an attempt to truncate them into codeable entities. And human users both rise to this entirely too well, with the collective ruthlessness of a virus seeking exploits and unintended effects, and subvert such truncation, finding ways to reinsert human aspiration and culture where they’ve been intentionally smoothed out of the workings.

Reciprocity rings at 500px and Flickr on one hand run almost like a moral economy alongside the meritocratic hierarchies built by the algorithms: some users work reciprocity hard and instrumentally to pump up each other’s reputation and images (and at some tipping point both reputation and images start to become self-sustaining social facts). Which often enrages both the “real” meritocrats and the aspirants who are trying to rise “honestly” through the genuine acclaim of others. It also affects the culture of commentary: very few comments express any constructive criticism or any detailed evaluation beyond “Great capture” (an especially silly comment when it is directed at both good and not-so-good images built through extensive composition in Photoshop). Even favoring with no comment creates an almost silent expectation of reciprocity. But any comment that is not an efficient offer of reciprocity also conveys some other human sociality, some possibility of connection beyond the algorithmic, as do the narratives or framing information that photographers offer with their images. All of which is complicated still further by the richly international nature of the site: “V + F” is a lingua franca in part because more detailed critiques would need translation into Spanish, French, Russian, Czech, Chinese, Hindi and many other languages to create dialogues between many of the most active contributors.

Algorithmic Eyes and Big Data

As your own favorites accumulate in a personal archive, you learn something about your own photographic eye, your readings of culture. But you also are retrained by the accumulation of images and your consumption of the totality of the site’s archive. An image that seems exceptional in its beauty and composition at first sight and would remain so if you stopped there and never looked again at the site becomes a cliche when something like it is seen again and again and again in the uploads of a hundred users. But in the best sense of meritocracy or evolution or capitalism, that same image can still be redeemed as wondrous if on the one thousandth iteration, a photographer of exceptional skill and vision offers their own version of the cliche.

The “big data” of an archive like 500px or Flickr shows patterns that are mined first and best through direct experience of navigating the archive. The user’s eye, clicking rapidly across and through the site’s interface, reveals structure and repetition but is also retrained and reoriented by that revelation. If I was setting out to be a successful commercial photographer and using 500px as an autodidactical tool, I would discover first many of the things that the standard pedagogy of photography tries to teach and second I would discover many things that an art historian or anthropologist of media might tell me about.

For example, spending a few hours watching thousands of images coming in as Fresh, rating some of them and tracking others, most users might recognize that successful images mostly conform to some of the basic norms of composition and craft in photography, whether they come from amateurs, professionals or people just sharing family and vacation pictures. Issues that are out-of-focus where they should be sharp, images that have multiple or no clear subject, images that don’t follow the rule-of-thirds without a reason for not following it, do not fare well. A viewer with no prior knowledge of these concepts might nevertheless begin to intuit them because of the pace and volume of digitized, algorithimic culture.

A few days or weeks of participation and most viewers could identify genres and tropes and subjects that get strong ratings from viewers without any knowledge of the history or circulation of those images. A list of image types often selected out by viewers might look like this:

Misty forests, especially with strong color contrasts or unusual color schemes

Sunsets, especially over water or agricultural fields

Pictures of circular bales of hay

Insect macros that contain narratives (the insect in motion, two insects having sex) or that offer dramatic color contrasts

Flower macros, especially of unusual flowers or flowers with intricate structures

Pictures of animals, particularly animals from the tropics, particularly animals from the tropics in the tropics

Star trails, especially over dramatic natural objects

Ultra wide-angle lens landscapes, especially those with small single buildings or people in the distance

Piers, paths, walls falling away into distance with leading lines pointing towards a distant dramatic object

Non-Western peoples in folk dress or ‘ethnographic’ poses

Soft-focus portraiture of women (nude and otherwise) in natural settings

Macro photography of water or liquid in motion

Still lives with strong color schemes and extremely sharp focus

Photoshop compositions of figures, landscapes and objects to exotic or fantastic effect

Small boats either floating or fallen apart on water or at the shoreline with strong color or textual contrasts

Birds in flight, especially raptors or large waterfowl

Spiral or fractal structures in architecture, usually shot vertically either looking directly up or directly down

And so on. All of which are cliches or tropes for a reason, because of their visual possibilities and the range of both aesthetic and technical understanding they can express. A more dedicated student of photography might also notice that certain strong genres of existing photography often don’t fare quite as well at 500px (but do pretty well at Flickr): B&W street photography, for example, doesn’t seem to climb very often to the top of Popular.

Someone reading for paratext might also notice that images with notes, stories or evocative titles often do better than those that do not. And certainly someone wise to the culture of the site itself would see where and how the workings of social networks and histories of presence within the site play a role.

The thing that’s new about algorithmic culture in this sense is partly what Haynes discusses in her book: that the “syncopation” it enables and produces is both showing us all something about how we already see and make and teaching us new ways to compose and design what we see and make: we discover in and are discovered by a site like 500px. We see the patterns, and the patterns teach us to make more of them, but also to remix them, deviate from them, improve upon them. We are never the solitary romantic artist or interpreter in that discovery or that creation: the algorithm is our co-agent, letting us, making us, traverse and annotate and generate a cultural technics that is so much vaster and richer and knowable than anything we’ve seen before, and is also more “us” than ever, more of us making and seeing and curating. But also making us see that there really are people (more of them than ever before) who compose and see and create differently and better than us: because the other category of image that often vaults to the top at 500px is the image that no one has seen before and is yet instantly familiar the first second that we encounter it, as if we have been waiting for it all along.

As we have been. Not just the us that clicks, but the we that includes our algorithms, made by us and making us. Managing our cultural spaces and unmanaging them, ordering them and sending them tumbling downhill towards strange attractors of all sorts. We spill out over the code infrastructures and interfaces–and that spilling, excessive us includes our technics, our machines, our programs, our pictures.