Maybe I had better read more books first.

Oh. I thought “sawhorse” meant you were supposed to saw it.

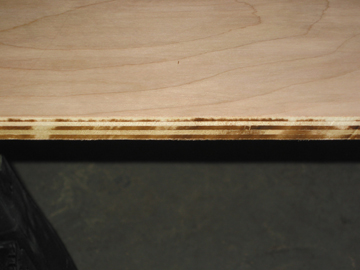

Do you smell something burning?

Oh, geez, I’m supposed to used scrap wood to keep the cut from pinching. But I don’t have any scrap wood. This’ll do.

No comment.

Is it too late to talk to your local joinery outfit? They most likely have that cool moving table device that produces exactly cut lengths of whatever in moments.

Yeah, I’ll probably do that in the future. I just want to learn myself first to do it as well as I can, if I’m going to be doing any woodworking in the future. It’s actually not quite as bad as I’m making out with these pictures. One shelf is going to have to be planed down and I have a bit of extra cutting to do on one of the sides, plus a lot of sanding. But mostly it went pretty well.

Setting the depth of cut to just greater than the thickness of the stock makes a better and safer cut. It puts more teeth on the wood since a larger arc of the blade’s circumference is in contact at any time, and they strike at a less perpendicular angle. This reduces blade bind, makes a smoother cut with less chipping on the surface (the blade rips up), extends blade life, reduces hazard to the things below the kerf (including your thumbs in some cases as well as your saw horses) and takes less effort to push the saw through the stock, often making it easier to cut a straight line. It reduces wear on the saw motor too since blade speed is higher and under less load. The saw is happier, the blade is happier, the wood is happier and innocent bystanders are safer.

Your intention to learn to do the work without too much automation, at first, is admirable. It provides an opportunity to ruminate about these issues and apply a bit of natural philosophy. One day, perhaps, it could provide opportunities for teaching a child some of the physical and mathematical principles behind the techniques noted above. To some this is just scut work better left to horny handed sons of toil, or machines, but when you also consider the math, physics and materials science aspects it can be informative, especially to a hungry young mind that still thinks that daddy might know something useful. This is a temporary opportunity since you will grow increasingly stupid, in her eyes, as she ages.

Thanks! Both on the practical advice and the more philosophical advice. You grasp my motives very well, including that this is “daddy work” of a sort. I think you’re exactly right that the mistake I made on the rip cuts was to have the blade depth far too deep. I sort of remembered that after the second rip cut.

It is important, for example, to discover for yourself that measuring with precision is authentically difficult. I abstractly sort of thought that was the easiest of all the things I was facing, but I’m now clear that it’s really quite difficult even when you get fairly good at this.

A bit of this is also just the physical awkwardness of a 8 X 4 X 3/4 sheet of plywood.

Tim,

As a regular reader who has just moved to Norristown (presumably not too far from you), and a woodworker by trade, I would be glad to give you any help you might need; tips on how to use the particular tools you have, answers to questions that don’t get answered in even very helpful books, even mill some wood for you if i can do so in a reasonable way. Consider it an offer of compensation for the enjoyment of I have gotten from your blog. Damn it man, you are the educated elite. You ought to feel a little entitled to call on the sons of toil in your time of need. (As long as they keep their horny hands to themselves, obviously)

Anyway, send me an email if the urge strikes. I took the same approach you have, but I am about fifteen years down that road.

That’s a lovely offer, Greg. Thank you. I may indeed have some questions and tip-seeking as I go along!

Great to see — I especially like the monkey to keep the cut from binding… I started a woodworking hobby about 4-5 years ago doing exactly the same thing, cutting up plywood with a circular saw on sawhorses. here are pix of the project, it gets even more fun after you (a) recognize that plywood is much better cut to size at the point of sale and (b) start exploring smaller and finer projects out of hardwood. I predict that at every step of your woodworking career you will wish you could do the measurements just a shade more accurately. Here is an excellent resource for woodworking advice and chat.

I just came to your site after having neglected it for a while so don’t know what you are building, but I am figuring after I post this I will browse some older posts and find out.

Sorry, here is a better link to pictures of my first bookcase project. After reading a few posts back I see you are coming to it from the same approach as I did — a desire for solid, sturdy bookcases that are neither Ikean nor exhorbitantly expensive.

Neat.

More updates on my own progress soon. Let’s just say I’ve hit a new snag: routers are hard to use!

It’s true. The nice thing is though, that they’re almost completely dispensible to the hobbyist woodworker — I assume you’re using a router to make dadoes? You’d be better off using your circular saw, set to cut only to the depth of the dado, and then clean it out with a chisel. Cutting dadoes with a router freehand is a fool’s errand — I am given to believe it is easier with a table-mounted router but I dislike routers enough that I have not tried.

It looks so easy in the book! But yeah, I’m trying to do dadoes and then also a rabbet to fit the bookcase back into.

It seems to me that it would be tough to do a 3/4″ wide dado with a circular saw and chisel. I can see doing that with a table saw and dado blades but that’s a level of expense I’m trying to avoid for the moment.

I think what I might do today is try to make a scrapwood jig for the router for the shelf grooves, because you’re right, there’s no way I’m going to pull it off freehand or even with a scrapwood straightedge guide.

One thing I’m finding makes measurements tough is the offset on the circular saw when I use my aluminum straightedge: I think that’s another jig I ought to build.

The thing about a scrapwood jig is in my experience, it’s very difficult to keep the router in the groove no matter how you have it jigged, because a 3/4″ dado bit exerts a tremendous amount of pressure (or force or whatever it is.)

Here is how to do it with a circular saw and chisel: clamp a straight piece of scrapwood against the workpiece parallel to the dado, and as far away from the (near) edge of the dado as dictated by the size of your circular saw’s base. (You have probably already measured this but if not, do so cutting a piece of scrap.) Make the cut, then move the fence over 1/8″, cut and repeat until you are on the far edge of the dado. It will be easy to clean out afterwards because the saw will have cut most of the waste out already. Takes a little while — yes, a table saw would be much faster — but the result is good. You cannot of course make stopped dadoes this way but I am assuming that is not what you need.

Oh and here is the best way to measure the offset of your circular saw: clamp a straight piece of scrap wood onto a scrap piece of plywood, on your saw horses. With a sharp pencil, draw a line on the plywood where the fence meets it. Then cut with the edge of the saw’s base riding against the fence, and take the fence off. The distance between the the pencil line and the cut line, is how far you need to offset your fence from your desired cut.

(I’m assuming you’re just using one blade — when you change the blade you should redo that measurement.)

I just did pretty well with a router dado, but I found it went a bit deeper than I expected it to–either I don’t understand the depth gauge on this model (a Bosch) or it can’t do anything shallower than 3/8″. But the primitive test jig I built did ok at keeping it to a straight groove. You’re right that it takes a lot of control, though–the damn thing wants to go somewhere else, all the time.

Still can’t get it to go a bit shallower than 3/8″, which leaves a pretty thin strip of plywood in the shelf sides. But the jig helps a lot. The damn thing still coughs and struggles and wants to jump out of the groove but I’m able to keep it going ok.

Cool — I didn’t have the patience to get the router to work properly I guess. That was the first (and to date, one of the few) woodworking tools I abandoned.