[This is my contribution to the Valve symposium on Douglas Wolk, Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean.]

————-

What happens when the tide of a media panic recedes? Fans of a particular media form or genre sometimes recount the history of its past persecution as medieval Christians dwelt on the gory particulars of the martyrdom of saints. Well they might, because the immediate aftermath of such a panic in the United States over the last century often has been shattered or badly disrupted creative or artistic careers on one hand, and stunted, forgettable cultural production on the other.

Yet, the odd thing is that the very act of heavy bowdlerization that hits post-panic cultural production in some genres and media forms sometimes sustains later devotion, creates a body of raw material that inspires later reworking, sets an aesthetic for authors continuing to work in the form. That which does not kill culture may make it stronger, but it also makes it more particular, builds a history of expectation and taste among consumers raised on post-panic practices of constraint and evasion. Just as fiction and polemic written as samizdat may seem more oddly alive and urgent than later work written under more liberal rule, post-panic cultural work becomes strangely, provocatively inbred after the wave of intense public scrutiny passes over the form, a hideaway that trembles for a long time at the thought of drawing renewed attention from an all-seeing eye.

At some point, however, cultural producers and loyal audiences realize that media panics rarely strike twice at the same target. In fact, they often seem to leave behind a sort of weak, generalized nostalgic mass affection for the form they once demonized. Now the problem for some creators and critics is habituation. They object to the way that an entire cultural form has been shaped by a path-dependent relation to its former persecution. They want to overcome its past fragility, and restore to the form what they see as its true cultural potential.

I think this is where Douglas Wolk’s enjoyable, interesting and useful book Reading Comics comes into the picture. There are a lot of great little nooks and crannies in this book: the second half consists of quick, smart sketches of the oeuvre of various comic artists and writers, and I could almost just stick to my agreements and quibbles with those alone. But as a whole project, it seems to me that Wolk is offering an extension, almost formalization, of Scott McCloud’s inauguration of comics criticism in Understanding Comics and Reinventing Comics. Wolk takes a lot of McCloud’s claims about the distinctiveness of comics as a particular form as a starting place and works outward from there. It’s a familiar strategy for authors who are trying to legitimate both a medium and a formal body of criticism of that medium.

I agree with Wolk and McCloud that comics are a distinctive form that requires a distinctive critical approach. McCloud’s concept of “sequential art” is a good foundation for building up comics criticism, and Wolk’s book is a good example of the quality of critical work that can be built on that foundation. But both McCloud and Wolk suffer a bit from what I think of as the Comics Journal Syndrome, a desperate need to redeem a post-panic cultural form to mainstream or academic respectability, to persuade a reader that comics are Very Serious and full of Untapped Potential (Except in Europe and Other Foreign Places With Better Culture Than Ours).

(McCloud on page 3 of Reinventing Comics: “Comics offers a medium of enormous breadth and control for the author–a unique, intimate relationship with its audience–and a potential so great, so inspiring, yet so brutally squandered, it could bring a tear to the eye.”)

Much the same thing happens in animation studies, in work on children’s literature, in critical work on videogames, in analysis of digital texts. There are a number of problems that this structure of argument creates as a charter for a school of cultural criticism. For one, it gets enmeshed in a rolling, provisional effort to separate out the high-art wheat from the low-art chaff in the new Very Serious critical version of the form. Wolk is savvy to this problem, but he sometimes still gets sucked into it, distinguishing “mainstream” comics work concerned largely with superheroes from independent work that operates across a wider terrain of genres and uses of the form, and seeing the latter as able to sustain sophisticated critical attention better than the former.

What this does in part is set up criticism as a permanently etic kind of practice, in rivalrous relationship to emic practices of readership that developed in part out of the savage truncation of the creative and aesthetic possibilities of comics after the panic of the 1950s. For many American comics readers today, for the wider American public consciousness of comics, and even for creators like Grant Morrison, the Comics-Code constrained, superhero-centered comics of the 1960s and 1970s are still the template that informs their expectations and imagination of comics now. Comics Journal Syndrome criticism inevitably sets itself up as a missionary force coming to rehabilitate the savages from their cultural backwater, to show them the Big City that they argue the form truly can be. When the savages shrug at the sight of the bright lights of Paris, they become one of the two enemies of the new critical form, responsible for reinforcing its limitations through their consumer preferences.

The other enemy becomes the wider apparatus of criticism, which is held accountable for refusing to make room at the table, whether that means tenure lines in the English Department or column space in the newspapers. Here comes the agony of the self-hating geek, all full of angst about his subcultural ghetto. “Yes, I read comics, but I’m not the Comic Book Guy, I’m a normal just like you.” In academic circles, the quickest way to get out of the ghetto after the ritual disavowal of the subculture is to run the form through a kind of orthodox historicist pummeling, to talk about its enmeshment in hegemony, the work it does with race/class/gender, and so on. In middlebrow criticism, you pick the works that seem most arty or edgy but that require the least translation for newcomers to see their quality. (Hello, paging Maus.)

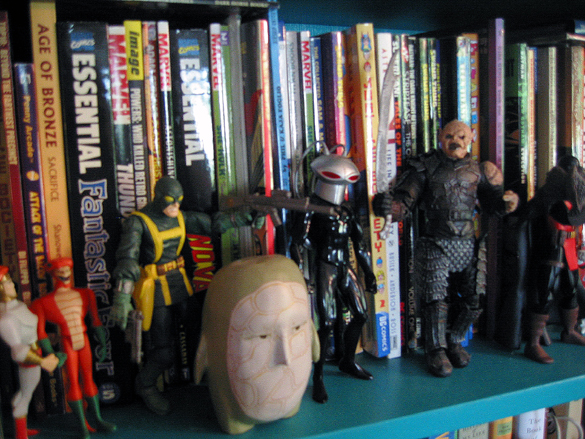

Wolk does some of this dance. He frets about comic shops, comic fans, the logic of collecting. To some extent, I have only one retort. Here’s my bookshelf:

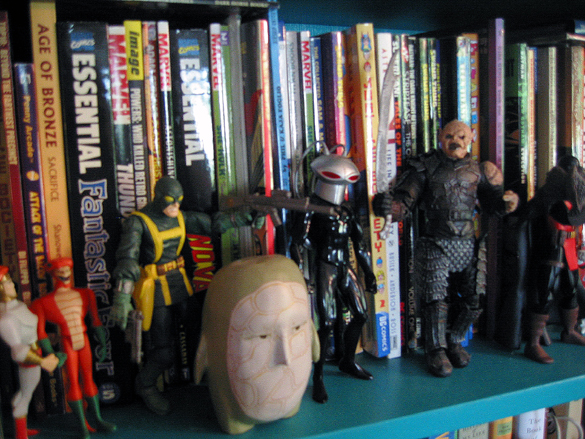

Here’s my closet:

I am the Comic Book Guy, right down to my physique. But that doesn’t get in the way of being able to operate as a scholarly critic or public intellectual in reading and thinking about comics, I don’t think. I don’t have to assimilate or disavow subcultural modes of appreciating or analyzing culture in order to talk about their importance or quality in a wider public conversation. Of course, I have tenure. It is also true that you have to be careful not to cross your nerd wires and have the wrong critical discussion in the wrong place. Talking about how (or whether) to reconcile Final Crisis #1 with Countdown is part of the dark art of geek hermeneutics. Talking about how Watchmen works as narrative is not.

To some extent, the apologetics that attend on a criticism founded by partial disavowal of the historical confusions of genre with form, by an attempt to make a criticism which is better than mere subcultural readership, has a tendency also to mistake generalized patterns in cultural production for particular dilemmas of the form which the critic is trying to redeem. For example, Wolk despairs of the endless self-referentiality and density of DC and Marvel’s superheroic comics, and the level of metaknowledge required to read them. Grant Morrison’s current work in Batman is pretty impenetrable unless you know about the aesthetics of the character in the Silver Age of comic-book storytelling generally and about a set of specific stories from that time period. But how is this different from the popularized sense of postmodern narrative generally? From the metaknowledge needed to read Pynchon or watch an episode of Lost ? If Wolk’s serious about this complaint, then it’s not about comics, it’s just the modernist cri d’coeur against the postmodern aesthetic. Which is fine, but it works better widened out to that context rather than as a plea for Untapped Potential that’s vested in a particular artistic form.

Superhero comics in shared-universes are a specific form and genre-bound case of pastiche, self-referentiality, intertextuality, sure. It has been interesting to see how the most successful transistions of superhero narratives to other forms require wrenching the characters and circumstances of their story loose both from the comic form and from the intertextual norms of shared-universe serial storytelling, like cleaning barnacles from a ship. Most movie superheroes exist either in ironic, deconstructed forms (Hancock) or they almost have to seem freakish, fetishistic, vaguely embarrassed by themselves. (Recall Liam Neeson’s Ra’s al-Ghul confronting Batman at the end of Batman Begins: he says something to the effect that Bruce Wayne kind of overdid it with his personal form of ninja theatricality.) What’s actually striking is that the superhero isn’t genre or form, exactly: it’s archetype. Superhero narratives, now that they’re being retold by audiences raised on them, move into new media forms and become native to them very readily, much as the Western once existed in profusion across many media forms but with major aesthetic distinctions and genre mutations across that spectrum.

In a way, what makes Wolk (and McCloud even more so) anxious is not the superhero, but the effervescently lurid four-color low-culture vitality of the commercial comic-book in the U.S. just before, during and after the Werthamite panic of the 1950s. As I wrote recently, one thing that David Hadju’s The Ten-Cent Plague does well is remind us that many of the most avid attacks on the comics came from the guardians of high culture and middle-class tastes, cloaked in language of concern for children. (Just as I would argue most of the attacks on television would come in the decade that followed.)

The challenge, I’d argue, is to invent a practice of formal criticism that doesn’t require this kind of anxiety, doesn’t vaguely internalize the disdain of high-culture for the vulgar and end up formalizing its criticism around an embedded apologetics. “Serious Fanboy” strikes me as a better modality for a comics criticism than “host of Masterpiece Comics Theater”. At times, that’s what I think Wolk achieves, at other times not so much. At least some of the most powerful work inspired in general by comics reading is not apologetic, whether it’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay or most of Grant Morrison’s oeuvre.

In some ways, the problem of the Unfulfilled Potential is not the business of criticism, and this is one reason that not so many people went on to read Scott McCloud’s sometimes heavy-handed Reinventing Comics. (Making Comics is much less suffused with manifestos: it’s just plain useful.) The problem of the Unfulfilled Potential is the business of artists, writers and publishers. I get a bit itchy even when small groups of creators start pushing some restrictive vision of how to “save” their chosen medium (Dogma 95, for example), but at least that involves trying to work out some idee fixe in artistic practice. Nothing can change the fact that the critic disposes, not proposes, and the work of Realizing Artistic Potential is about proposition. It’s up to the critic to call attention to it once it has happened, and really, hasn’t it already? When I bought my first comic book (Justice League #133, if you must know) off a rack in a pharmacy, there wasn’t anything else there besides superheroes, Archie, Richie Rich and Disney. If I’d been a talented pervert, I might have been able to get my hands on some “underground comix”, but come on, go take a look at the graphics novel section of a medium-sized Borders if you want a sense of how much has changed in terms of the potential-fulfilling uses of the form.

But you know, for all that I catch a strong whiff of Comics Journal Syndrome around Wolk at some junctures, he really avoids getting too caught up in these traps. First, because he’s exceptionally self-conscious about these issues, and talks about them explicitly throughout the text. He follows up talking about how he hates comics subculture by talking about how he loves it, with an acute sense of the problems I’ve talked about in this essay.

Second, because he’s remarkably open, accessible and clear-headed in his view of cultural criticism as a device for the systematic discussion of good work and bad work within a form, something that much academic literary criticism has largely shunned in the last few decades. This is not a historicist account of comics-as-window-into-society, for the most part. In fact, it’s delightfully old-fashioned in terms of its delivery of substantive criticism, chock-full of rich interpretative attention to specific texts, to thinking about comics auteurs, to a great command over the medium’s permutations and varieties.

It’s a fantastically teachable book that you could plug into any course on cultural criticism, and a great way to normalize work on comics inside that larger structure. I just think Wolk could consistently follow his own advice to Chris Ware: there is never any need to push aside fun in order to convince people that you’re Very Serious.