Julian Fellowes’ Downton Abbey is fun and fascinating TV for lots of reasons. It has an excellent script and superb acting, and the detailed development it gives just about all the major and minor characters is smartly set against a backdrop of dramatic social change as World War I invades the courtly rhythms of daily life at the Grantham’s Downton Abbey estate and the village nearby. It’s Upstairs Downstairs merged with Brideshead Revisited, but with more angst and turmoil for our even more dangerous and uncertain times.

In episode 3 of Season One, though, something really strange happens — a nighttime scene of seduction that is hallucinatory, melodramatic, and almost completely implausible, both in its set-up and, especially, its outcome. The episode involves a handsome young Turkish diplomat or embassy attaché, Kemal Pamuk, who tries to (and does?) seduce the eldest daughter of Lord Grantham, the owner of Downton Abbey. How should we understand what happens? Why does this so smoothly modulated series so lose its composure when sex and an ethnicity foreign to “Englishness” suddenly become central? For the presence of a Turkish seducer not only makes Lady Mary act almost completely out of character; it briefly throws into disarray of the stately pacing of the entire show.

1.

First, a few comments on that great pacing—part of what creates Downton Abbey’s extraordinarily successful balance of intimacy and sweep, careful character portrayal and dramatic social history. Particularly intriguing is the show’s exploration of the changing meanings of class divisions in England during the era before and during World War I. U.S. TV shows just don’t do class well. When they tackle the subject at all it is primarily through caricature. At first glance, it may seem that Downton Abbey is only about the eternal British social divisions, where “everyone has their part to play,” as Lord Grantham expounds at one point. But a closer look, which each episode encourages us to do, reveals that everything that seems so stable about the British class system is actually shifting right before our eyes under the pressure of modernity.

To begin with, there’s considerable instability among the elite. This is primarily emphasized by Lord Grantham’s family’s long-running discussion about how best to cope with the fact that, unless a legal “entail” is broken, their country estate and fortune may very well have to go to the closest surviving male heir, Matthew Crowley, a third cousin once removed, rather than to Lord Grantham’s eldest daughter. Some members of the family are particularly scandalized because the potential heir is not just a mere appendage on the family tree; he holds down a solicitor’s job in the grubby industrial city of Manchester. (Grantham is the family title; Crawley remains the family name. One of the readers of this essay kindly corrected my confusion on this point.) Matthew and his mother represent the rise of the English professional middle classes, and in a good many cases older aristocratic families had to make alliances with this new class in order to continue. Lord Grantham himself is an example from a generation earlier of such a strategic alliance with new money, for he too has been something of a class transgressor. He can keep his huge country estate in such pristine condition in part because he married Cora, a Jewish American millionaire whose fortune derives from her father’s dry goods business in Cincinnati. (It’s positively Henry Jamesian!)

Lord Grantham’s shrewd rebelliousness has been inherited especially by his youngest daughter, Sybil, who supports votes for women, scandalizes her grandmother, the formidable Dowager Countess, with her plans to work, and despises the class system that gives her freedoms while of course also binding her with all the obligations befitting a lady. Once the War gets underway, of course, these kinds of transfigurations of individuals and the class system as a whole accelerate, for social connections occur in the trenches that would be impossible at home. Thomas, the first footman in the Grantham household, hosts Matthew Crawley, an officer, for tea in a bunker, for instance. Upheavals on the home front are just as dramatic, as symbolized by Downton Abbey’s plush rooms filled with doctors, nurses, and recuperating soldiers.

Downton Abbey raises fascinating questions about whether such changes in the British class system were structural and permanent, or temporary and superficial. Lord Grantham is proud of his boundary-crossing, but he understands it merely as expediency that he had to undertake in order to stay true to immortal British hierarchies. In the end, as he says to his possible heir, he sees himself merely as a “custodian” of the Downton Abbey estate responsible for keeping it up and passing it on properly to the next generation. Social changes for him are mostly merely on the surface of society; underneath, the deep structure and ordained stratifications of British society must and should remain, a kind of eternal play in which, as he says, we all have our parts to play. He gives little sense that he can imagine the scripts being radically revised, though perhaps his daughters would have other opinions about this. Lord Grantham’s mother, the Dowager Countess, not surprisingly, sees things similarly. As she puts it to Lady Sybil in an episode in Season Two, warning her, “War breaks down barriers, and when peacetime re-erects them, it’s very easy to find oneself on the wrong side.”

More change may occur in the basement of the great house than in its parlors. To its credit, Downton Abbey shows great interest in the changes occurring “downstairs” among the working classes, including the many Irish and English maidservants, cooks, footmen, valets, and others employed by the Granthams. In Season One, episode three, for instance, the maid Gwen is secretly studying typing and stenography in the hopes of being able to leave “the service” to strike out on a different career path in a city—one that she hopes will allow her to join the middle classes. Several of her superiors among the servants, most notably O’Brien, are disgusted by her secret plan when it’s revealed, while others are just made uneasy. It’s left to the two most sympathetic and generous servant characters, Mr. Bates and Anna, and the most rebellious of the Grantham daughters, Lady Sybil, to reassure Gwen that she should pursue her dream. (A scene in episode 3 involving Mr. Bates and Anna and Gwen is particularly affecting because both Mr. Bates and Anna at this point are uncertain about their own futures.) Further, by having Lady Sybil be so supportive of Gwen, Downton Abbey is suggesting that some elements of the English upper classes actively encouraged social mobility among the working classes. It would be interesting to find out how true this was, or whether a character such as Lady Sybil represents Julian Fellowes’ fanciful wish—as a Conservative Peer in the House of Lords as well as the primary script-writer for and creator of Downton Abbey—about how things might or should have been.

Gwen’s dream of upward mobility and Lady Sybil’s support, of course, are dramatically juxtaposed against the Dowager Countess’ proclamation that the lower classes should not “rise above their station” but do the work they were born to do. Nonetheless, Downton Abbey repeatedly shows that no one, rich or poor, may have a fixed “station” any more, despite what the rich think. Some of the Downton Abbey staff are exhilarated at these prospects, while others are wary or fearful about them. But just about all the characters, not just a privileged few, face life-changing choices. It’s the despicable characters, like O’Brien and Thomas, who are most sure of what they want and how to plot to get it, while it’s the honorable characters who most struggle how to reconcile personal hopes for change with their sense of obligation to others around them.

2.

Given all this nuanced writing and careful character development in Downton Abbey, it’s especially surprising when episode three in the first season suddenly gets a fatal attraction to sex, male power, and the allure of the East. A handsome young guest shows up in daughter Lady Mary’s bedroom in the dead of night and seduces her (or rapes her, if that’s your view)—in the end it’s pretty unclear just exactly what happens sexually between them. It’s true it may a slight overstatement to say these developments are completely implausible, for Lady Mary has clearly become more than just a little intrigued with the dashing young man who has proven such a good horseman during that afternoon’s fox hunt. When they return from the hunt, their fine clothes are fetchingly bespattered with drops of mud, their skin is flushed, and they can’t take their eyes off each other.

But Lady Mary allowing herself to be seduced is not really in character. She’s been portrayed up to this point as a very strong, controlled, and controlling person—haughty, austere, with a very high opinion of herself and her beauty, not to mention a constant awareness of her unique responsibilities as her father’s eldest daughter. Julian Fellowes the scriptwriter tries to finesse this contradiction by having Lady Mary be angry and resistant at first to the young man’s invasion of her bedroom. But in the last shot of them together that night we see her eventually embracing him and kissing him back. The show apparently believes that she wants to give up being so responsible; her “no” doesn’t really mean no.

The real question here is, how does Downton Abbey portray the source of Kemal Pamuk’s powers to Lady Mary? Is it his prowess on horseback, his cheekbones, or something else? What’s the relevance of the young man being Turkish?

To answer that, we must first consider what hints we have about what happens behind the closed door. First, there’s a suggestion that Lady Mary, the epitome of self-control and self-regard, wants to be violated, and he’s just the man to do it. Then something even odder occurs. Pamuk is in his twenties, active and healthy and obviously sexually experienced, but having sex with Lady Mary gives him a heart attack. What?? When we next see Pamuk, he is lying naked on the bed barely covered with a sheet and staring vacantly at the exquisite wallpaper. Lady Mary, the head housemaid, and Lady Grantham (Mary’s mother) desperately try to figure out how to lug Pamuk’s body back to his guest bedroom before daybreak to avoid a major scandal. Julian Fellowes would no doubt plead that this episode is based on a historical fact—a foreign diplomat did indeed die in the bedroom of the daughter of his host in one of the country houses whose history Fellowes researched for Downton Abbey. (See http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/downton-abbey/8820907/Who-is-the-historical-model-for-Downton-Abbeys-sex-scandal.html [.]) But was this foreign diplomat really a healthy 20-something? I’d be surprised. Even if so, so what? What is historically factual is not always plausible in a fictive world—especially one that prides itself on its nuanced realism and one that has given us the kind of character that Lady Mary is.

Since the young man is Turkish, this means means that suddenly issues of race or ethnic difference have been introduced into the plot, not ones focusing on romance, or gender, or class among the English and Irish. How is Pamuk’s Turkish identity represented in Downton Abbey? Well, here’s where it gets really interesting—and kinky, and relevant to the question of what really happens behind closed doors.

To begin with, because Pamuk is a Turkish diplomat he represents a dangerous rival to the British empire, the Ottoman Turkish empire. (His first name, Kemal, also recalls the name of great early twentieth-century Turkish leader, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.) Pamuk’s portrayal on the show is completely schizophrenic. He’s both more English than the English when it comes to certain skills, including horsemanship and the ability to captivate English maidenhood, and yet in most other ways he’s portrayed as an uncivilized rake, a barbarian, a man far handsomer, skilled, and ruthless than any of his English rivals. Underneath his smooth veneer, Pamuk is, the show suggests, primarily driven by sex—that’s the real fox hunt going on here. Even more dangerously, to an “English” point of view, is the fact that Pamuk is able to ignite an ungovernable sex drive in others—not just in the normally adamantine Lady Mary, but also in Thomas, the normally hyper-controlled head footman.

And what kind of sex is it, really, that Downton Abbey wants us to believe proves so irresistible to Lady Mary? It’s not clear what sex Pamuk and Lady Mary have, but we do know what he says to her beforehand: he tells her he knows how they can enjoy sex without vaginal intercourse (“Don’t worry, you can still be ready for your husband”). This suggests that he’s either going to teach her techniques that will really make her “ready for” a new husband, or, more primly interpreted, that he pleasure her and himself while still leaving her technically a virgin, with oral sex or something more shocking. (As one blogger coyly put it, alluding to Last Tango in Paris, “Oh, dear. I sure hope Thomas carried a stick of butter into Lady Mary’s chambers.” What lurid imaginations some in the Downton Abbey audience have!)

And don’t forget, earlier Pamuk had gotten Lady Mary’s attention with the alluring comment that “Sometimes we must endure a little pain in order to achieve satisfaction.” A little S&M, perhaps, stimulated by all those horses earlier being whipped by riding crops? The script’s suggestiveness here is coy but clear. Under this suave Turk’s civilized veneer lurks savagery, a lust for the domination and humiliation of others—or at least a bit of controlled violence and pain mixed with pleasure. Worst of all, but also most exciting perhaps, is that this English virgin (or part of her anyway) is attracted to being seduced by such a man.

Pamuk is surprised by death, but Lady Mary afterwards endures a kind of death of her own. We watch as in scene after scene her whole marble veneer crumbles. She cries and has to leave dinner parties, pleading headache. And when speaking with Matthew, she suddenly admits to being frustrated by her life: “Women like me don’t have a life. We choose clothes and pay calls and work for charity and do the season, but really we’re stuck in a waiting room until we marry.” This comes close to despair, and is a far broader response to the debacle than just bewilderment at her behavior that evening, or shock at Pamuk’s death in her bed. Something about him, or her, has caused all her confidence to collapse. Why? Lady Mary’s sense of the gap between her behavior that night and what is expected of her as the eldest daughter of Lord Grantham? The sex she had, the death that occurred, or some grisly intertwining of the two? Whatever it is, she now sees her life as farcical, living in a mere “waiting room” until a husband comes and defines her. (But it’s not as if the life of a lady will be much different, for she knows it too will revolve around clothes, calls, charity….) Pamuk’s male rivals among the gentry, like Evelyn Napier, the aristocrat and friend who brought him to Downton Abbey, express just rueful acquiescence to being bested as males by Pamuk. Lady Mary’s response to Pamuk’s virility and demise is much stronger. She now doubts the validity of her entire existence—and the existence of all women like her. She’s overcome by lassitude, doubt, and despair and spends a lot of time sitting and lying around in langorous depression.

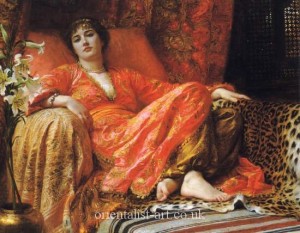

Is there a precedent or analog for Lady Mary’s posture and mood? Well, yes. In many ways it’s not unlike the poses of light-skinned women shown in harems in paintings popular with the English in the nineteenth century, such as this one from 1892 portraying a courtesan named Leila after sex. It’s by Sir Frank Dicksee, who was knighted for his work, and it’s now in the collection of the Tate Gallery, London. (See below.)

The English in the Edwardian era were obsessed with the sexuality of Turkish and Arabian women in harems—and its aftereffects, if that’s the right word. They were thrilled yet horrified at the belief that women in harems were chattel completely at the mercy of male power, imprisoned in hidden spaces, surrounded by luxury yet also full of a kind of otiose melancholy. There’s more than just a hint in Downton Abbey that Lady Mary, disillusioned about her future and with her reputation in danger, feels as if she too is now imprisoned chattel. Though supremely privileged, she feels bound not just by her own bad choices but by male power and prerogatives, “trapped in a waiting room” as she puts it. Of course the harem analogy goes only so far: the males who rule Lady Mary’s fate are English, not Turkish. But Pamuk’s seduction of her will have far-reaching and as yet unknown consequences for her and her family: O’Brien schemes how she can use the rumors, gossip circulates in London, and even Lady Mary’s sister Edith, after a spat, decides to write the Turkish ambassador about her suspicions in order to get revenge on her sister.

Two Grantham male heirs die by water—one on the Titantic, to open Season One, and one related to a bathtub fall, to close Season One. Over the last one, Matthew Crowley, is cast a shadow: he can’t know whether Lady Mary is attracted to him for himself or for his probable inheritance. Just as maddeningly, when Lady Mary distances herself from him, as she often does, she seems also to be struggling with knowing whether she’s acting prompted by money or by her heart. When she tells him “don’t trust anything I say,” it’s hardly helpful. But why is Lady Mary so tangled up about her own desires? It’s arguably not mainly the legal “entail” that is causing this, but a forbidden piece of tail she had the night after a foxhunt. The narrative tension sustaining Seasons One and Two of Downton Abbey is primarily formed by the question of whether Matthew and Mary will unite. If not, Lord Grantham’s daughters will be legally exiled permanently from their father’s and mother’s money and land. All they will get will basically be charity. A Turk who’s present for part of just a single episode thus plays a huge role in Downton Abbey’s eventual outcome.

And it’s not just the Granthams who are shadowed by the specter of the Turk. The allure and threat that Kemal Pamuk presents to the English gentry itself is quintessentially Orientalist. Pamuk can outdo them at their own rituals and then violate the English behind their backs. Yet these are not just centuries-old English fantasies and fears about Turkey and the Orient that we are entertained by, but a TV show written for broadcast over a century later, in 2010-12. Underneath our continuing fascination with and fear of “Oriental” sexuality perhaps lies a still painful and still unresolved unease with the fate of British character and the British empire itself.

****

A footnote before I move on to the issue of how other people’s sexuality is portrayed in Downton Abbey. The model-handsome actor playing Pamuk, Theodore James, is anything but Turkish. His online bio says he’s English, Oxford-born. But then again his real last name, until it was changed, wasn’t James but Taptiklis, which is Greek. Also of interest: Julian Fellowes himself has connections to the Arab world, for his father was an Arabist and a diplomat and Fellowes himself was born in Cairo. An author can have connections to the Arab world and still be seduced by the tropes of Orientalism, however.

3.

Most of Downton Abbey is not high melodrama and lurid suggestiveness about sex, of course. It’s about the difficult life choices everyone faces, even the most privileged, and at the end of Season One none of the characters get what they have most wished for except Gwen and Sybil (and perhaps Mrs. Patmore). In regard to sex, most of honorable characters in the series, aristocrats and servants alike, learn they must defer sexual pleasure. Precisely here is where Downton Abbey strongly suggests that—despite Lady Mary’s and Pamuk’s acts, and despite all the monstrosities that World War I inflicts—British character remains solid and strong. For all the heroes in the show, male and female, gentry and servant, know that “character” means self-control.

The alliance that appears to be most active and sexually healthy, Lord and Lady Grantham’s, is pointedly one first forged for financial convenience; it was only after the marriage, Lord Grantham boasts, that he then fell in love with his wife. Through such details and plot-lines, Downton Abbey hints that the power of sexuality is so volatile that it is best corralled within strict social structures.

The other marriage that figures prominently in the plot is Mr. Bates’, and it’s a nightmare whose sulfuric fumes we can just smell behind Bates’ grim silence about unmentionables in his past. Sex, of course, hardly seems the source of Mr. Bates’ problems with his wife, as opposed to greed, slander, and revenge. But Mr. Bates’ strict control of his attraction to the maidservant Anna is coded strongly as one of the things that define his new self’s integrity. It’s a strange kind of honor based on shame: he’s so ashamed of his own past that he refuses to defend himself against allegations that he knows to be false. But the show suggests that’s the most honorable thing about him.

When it comes to the two most scheming and unlikeable characters in the show, the servants O’Brien and Thomas, they too follow the general pattern of keeping a tight control over sexuality. This is what makes them so interesting, as if they are demonic inversions of what makes other characters “good.” For both O’Brien and Thomas, for the most part, are masters of self-control, not to mention disguise. In both their cases, furthermore, their sexuality is cast as deviant, though in different ways. Thomas, like Lady Mary, ironically, can’t resist Pamuk’s devilish charms. For someone as ruthlessly selfish and intelligent as Thomas is—he knows the war is coming before anyone else, and secures a medical assistantship that he believes will prevent him from being sent to the front lines—succumbing to an urge to paw Pamuk proves to be a dangerous slip in his normal icy self-control.

As far as O’Brien goes, she’s a mystery. Whatever her past has been, she seems now completely sexually repressed, more aroused by power and revenge than any prospect of sex. Yet she’s also obsessed with others’ sexuality and constantly alert to how it may make them vulnerable to her. (Thus in particular her shrewd and accurate guess about what happened in Lady Mary’s room, and her obsession with calculating how best to use this information.) Then there’s the case of O’Brien’s strange hairdo, featuring curls on either side of her forehead like curtains. She has a strange idea of beauty; it’s not clear whether she regards her hairstyle as making her look respectable, or whether she’s just indifferent to how she looks. [One commentator on this essay suggested that O’Brien’s hairstyle is Victorian, revealing how fundamentally old fashioned she is. That may be right.] This odd blindness or backwardness in O’Brien regarding her appearance contrasts with other elements in her character, which are all about her future survival and control, such as her doling out attentiveness and deference as she manipulates Lady Grantham.

Whatever O’Brien’s mystery and her past are, there’s a powerful undercurrent of something dangerous going on in all her scenes with Thomas, swirling in the air as fitfully as the smoke from their constant cigarettes. She seems old enough to be his mother, yet they repeatedly stand or sit together as closely and intimately as conspirators or lovers. Of course many things shift dramatically at the end of Season One, and one of them is that O’Brien scares even herself in the lengths she will go to keep her position in the Grantham household. Thomas, meanwhile, secures his way out and leaves O’Brien without a look back.

4.

I’m not sure how to conclude this. Lots of conclusions suggest themselves. But this piece has long been too long, so I’ll offer one last thought. For a series so fixated on the virtues of self-control—with Lady Mary’s and Kemal Pamuk’s escapade being the prime example of the havoc let loose when self-control is lost—Downton Abbey in the end may suggest that those who best survive the world’s changes do so not through self-control but through acts of generosity performed with grace. The Dowager Countess decides she doesn’t need to win the prize for Best Rose yet another year and gives it to a humble gardener. Mr. Bates breaks the rules for once and offers a tray of tea decorated with a flower to a sick Anna. Sybil helps Gwen, making the youngest of Lord Grantham’s daughters happy in a way sharply contrasted with her sisters. Matthew says “I couldn’t steal your life” to Lavinia, his fiancée, after his wound, an act of courage that takes even more guts than anything he did on the battlefield. And Lady Mary in particular makes one gift after another to others in the final episodes of Season Two, including to Matthew and to Lavinia. It’s true she does this rather gritting her teeth and willing herself to do it. But she does it. By the end of Season Two she may indeed have grown more than any of the other characters.

Of course, being a good Brit, and a writer honorably in the lineage of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, not mention Upstairs Downstairs and Brideshead Revisited, Julian Fellowes would perhaps offer the observation that no act of generosity can be performed without self-discipline.

Sources

Blogger “MarlyK” on the bedroom episode: Basket of Kisses: Smart Discussion About Smart Television. http://www.lippsisters.com/2011/05/18/downton-abbey-–-episode-3-–-do-you-promise-not-to-tell/

On Julian Fellowes: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_Fellowes

On Downton Abbey characters in general: Enchanted Serenity Period Films Blog.

http://enchantedserenityperiodfilms.blogspot.com/2010/09/meet-characters-of-downton-abbey.html

Clive Aslet, “Who Is the Historical Model for Downton Abbey’s Sex Scandal?” The Telegraph 11 October 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/downton-abbey/8820907/Who-is-the-historical-model-for-Downton-Abbeys-sex-scandal.html

For the Dicksee painting, see The Tate Gallery’s website “The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting” (2008).

http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/britishorientalistpainting/explore/harem.shtm

3 Responses to What Should I Do With the Dead Turk in the Bedroom? Class, Sex, and Otherness in Downton Abbey