I enjoy working with National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) return data, but the differences between the way schools report Degree Titles can be frustrating. For example, here’s just a few of the ways “juris doctor” can appear:

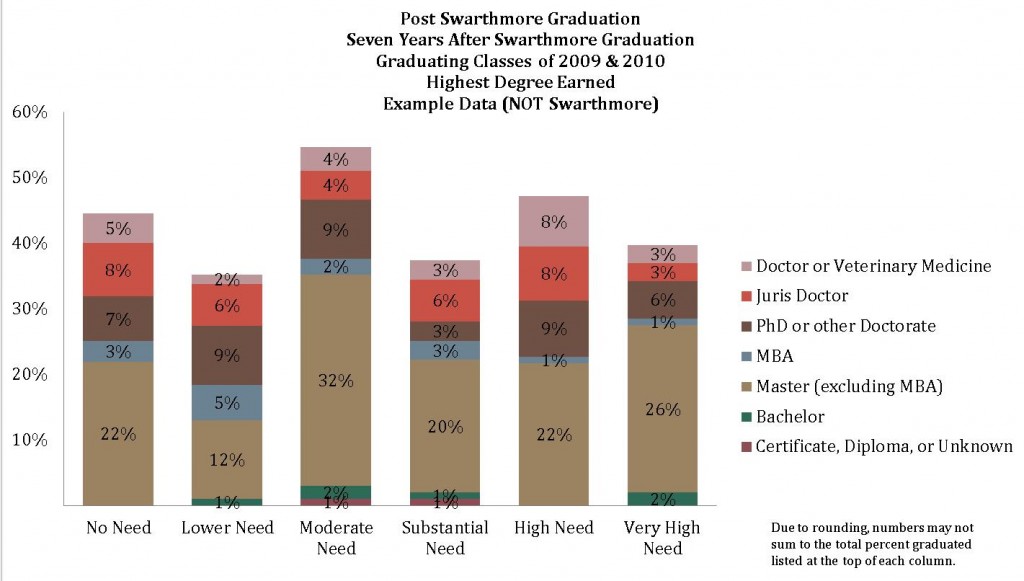

I’ve worked on a few projects where it was necessary to work with the type of degree that was earned. For example, as part of Access & Affordability discussions, it was important to examine the additional degrees that Swarthmore graduates earned after their Swarthmore graduation by student need level to determine if graduates in any particular need categories were earning certain degrees at higher/lower rates than other need categories.

In order to do this, I first had to recode degree titles into degree categories.

The NSC does make available some crosswalks, which can be found at https://nscresearchcenter.org/workingwithourdata/

The Credential_Level_Lookup_table can be useful for some projects. However, my particular project required more detail than provided in the table (for example, Juris Doctors are listed as “Doctoral-Professional” and I needed to be able to separate out this degree), so I created my own syntax.

I’m sharing this syntax (below) as a starting point for your own projects. This is not a comprehensive list of every single degree title that has been submitted to the NSC, so be careful to always check to see what you need to add to the syntax.

While I have found this to be rarer, there are the occasional degrees that come through without a title in any of the records for that degree. I’ve therefore also included a bit of syntax at the top that codes those with a Graduated=”Y” but a blank Degree Title to “unknown.” If you are choosing to work with those records differently, you can comment out that syntax.

Once you have created your new degree categories variable(s), you can select one record per person and run against your institutional data. One option is to keep, for those who have graduated, the highest degree earned. You can use “Identify Duplicate Cases” to Define Matching Cases by ID and then Sort Within Matching Groups by DegreeTitleCatShort (or any other degree title category variable you’ve created). Be sure to select Ascending or Descending based on your project and whether you want the First or Last record in each group to be Primary.

Hope this helps you in your NSC projects!

SPSS syntax: Degree Title Syntax to share v3