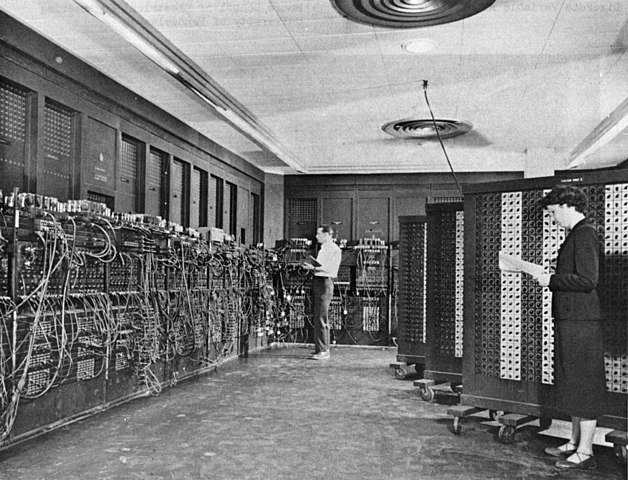

In the early decades of modern computing – the 1960s and 1970s – only the largest corporations and governmental agencies had access to computers of any kind (think IBM, NASA, DoD, etc.). Computers were too large, too challenging to maintain, and required too much specialized knowledge to use effectively for the vast majority of companies, much less individuals, to leverage. The advent of Intel’s 8088 processor, and its adoption by IBM into one of the first true mass-market personal computers (and yes, other incredibly influential systems that used different processors, such as the Apple II and the Commodore 64), heralded the first wave of democratizing access to computational technology; it was now possible for a wide range of businesses, schools, and consumers to exploit the potential of such devices.

Thus began a perpetual race among businesses and institutions of all types to have the biggest, fastest, shiniest computer. After all, faster time-to-insight could provided a gigantic competitive advantage. Academic institutions as well started to build their own datacenters housing increasingly powerful systems, in a bid to attract the best and brightest researchers. Understandably, certain names became leaders: Cal Tech, Princeton, Harvard, and indeed nearly every “R1” school. Truly powerful computational technology was once again gated, but this time much of it was sequestered within the Ivory Tower of academia.

Such was the case for a few decades. Recently, however, the availability of cloud computing made the promise that anyone, no matter where you worked, could leverage almost unlimited computing resources. It no longer mattered – or so we were told – whether you were a researchers at Rutgers, or at Swarthmore, or at <insert school here>. Now you, too, could research the same questions anyone else could. This was supposed to “democratize” research and level the playing field, as it were.

Did this work? Has this lofty promise been fulfilled? Well, yes, and no. It is true that cloud computing is reasonably available to nearly anyone, from nearly anywhere. But it remains comparatively expensive for all but the most relatively trivial use cases (Do you need, e.g., large persistent storage, fancy GPUs, or long run times? Break out the checkbook.) Even “free” national supercomputing resources (such as ACCESS) have limitations and a learning curve such that those without some kind of local support might feel overwhelmed.

This means that – for now – local resources are still “king.” We are incredibly lucky at Swarthmore to have Strelka as a resource for teaching, learning, and research. Members of our community can indeed conduct research, pursue projects, and deploy pedagogical strategies that were not possible here even a few years ago, and that remain sadly out of reach for many other institutions.

Where is this headed? It’s hard to say. The promise of quantum computing, for example, is immense, but I believe this is an inflection point, much like where we were in the 1950s and 1960s. Once more, only the world’s top agencies, companies, and governments will even have such systems, at least for some amount of time (don’t expect to see a quantum computer at Swarthmore in the near future!). Perhaps cloud computing will ultimately succumb to an economy of scale, meaning we won’t need to house a computing cluster locally (and all the related infrastructure, such as a datacenter). Whatever happens, the path ahead is certainly not boring!