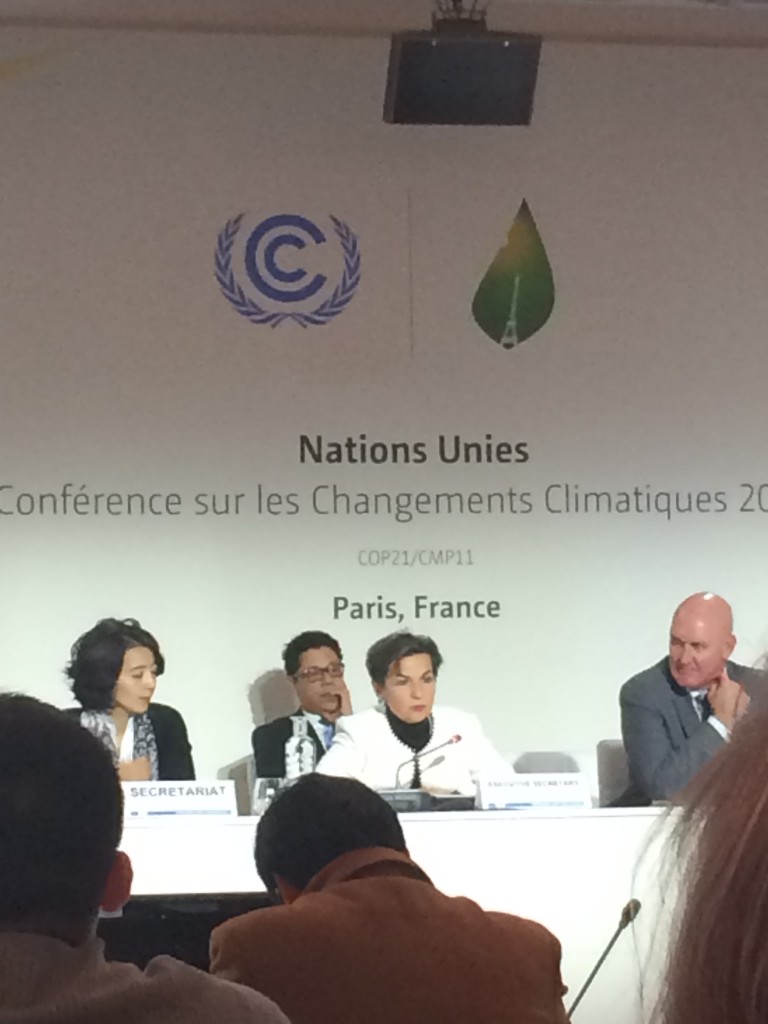

Technology ultimately plays a large role in the actual, physical mitigation and adaptation plans established by different parties and organizations. However, it should be noted much of the discussion of “technology” that goes on in the COP21 is pretty far removed from the actual science. Many bodies of scientific experts such as the SBSTA that are part of the COP simply compile and submit relevant recommendations for the COP to consider and can only influence the negotiations indirectly. Policy initiatives and mechanisms that integrate technology and are designed to aid for instance, Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS), seem to be largely set up to provide “technical assistance” or “capacity-building” and act as networks that connect these government entities with other firms that are concentrated bodies of expertise.

During one of the side events I sat in on, I found that the Climate Technology Center & Network (CTCN) is exactly that, and is coincidentally recognized as the operational arm of the COP21 in this regard in conjunction with Technology Executive Committee (TEC) which is the policy recommendation arm. Through the CTCN, no finance is provided for projects nor actual technological solutions, but simply feasibility studies and other “requests” for technical assistance which governments who need the help must actually formally submit for through Nationally Designated Entities (NDEs) defined by the requesting country and then pay up to hundreds of thousands of USD ($100,000-200,000) for the services. Arguably, these countries can seek funding from other sources to pay for these services, but it brings to mind questions about whether technology is really being effectively implemented in this way given their already limited resources. If this is the process that a developing country must go through in order to simply identify which technologies to implement, I fear how the combined lag of international policy bodies to make decisions, these intermediate phases of technological development, and the actual implementation of technologies will affect our ability to cope with climate change when our preparation time is already in short supply.