Why You Should Care about INDCs?

INDC is one of the most frequently mentioned words at the COP ground. INDC stands for Intended Nationally Determined Contribution, which constitutes the Parties’ (i.e. countries who have ratified the UNFCCC) plans to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. INDCs provide an alternative to a top-down approach to emissions targets, which have failed due to gridlock and disagreement about countries’ individual commitments.

As the name indicates, the concept of INDCs creates significant flexibility for governments to formulate and commit to their own pace and magnitude for emission reductions. But with this flexibility comes some tough questions – who would enforce these INDCs? How can they be monitored? Monitoring and verification, so far, continues to be an unresolved issue. The updating of the INDCs is also a pertinent question, as they are meant to set realistic goals with what is known today with a view to becoming more ambitious over time, as new knowledge – such as new technology or new pricing on existing low carbon technology – become available.

And, then, there is the question of whether the INDCs will add up to the goal of keeping global warming to a maximum of 2 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels? A new report by the UNEP on the emissions gap indicates that: “Full implementation of unconditional INDCs results in emission level estimates in 2030 that are most consistent with scenarios that limit global average temperature increase to below 3.5 °C (range: 3 – 4 °C) by 2100 with a greater than 66 % chance.” In other words, the current INDC commitments put the world on track for 3.5 °C by 2050, nearly twice the limit agreed upon at COP15 in Copenhagen. While this is not good news, the event we attended this morning discussing the report emphasized that the flexibility built in to the INDCs can permit the ratcheting up of the ambitions. Some countries here, particularly developing countries with high levels of vulnerability, have pushed to include the 1.5 degrees target as opposed to the 2 degrees. The current draft language includes in brackets – i.e. as possible but yet undecided – “below 1.5 °C” or “well below 2 °C”.

Despite potential shortcomings, INDCs also offer advantages: they have helped to bring almost all countries on board with plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and they aid in the creation of differentiated targets that allow each nation to address its most pressing issues.

We will be attending more events on INDCs and will post relevant updates. You might want to visit the following website for updates and graphs on INDCs: http://cait.wri.org/indc/\

– Anita Desai, Stephen O’Hanlon, Ayse Kaya

Follow us throughout the week on Twitter (@SwarthmoreCOP21) and Snapchat (SwarthmoreCOP21) to get real-time updates.

Kicking off the second week

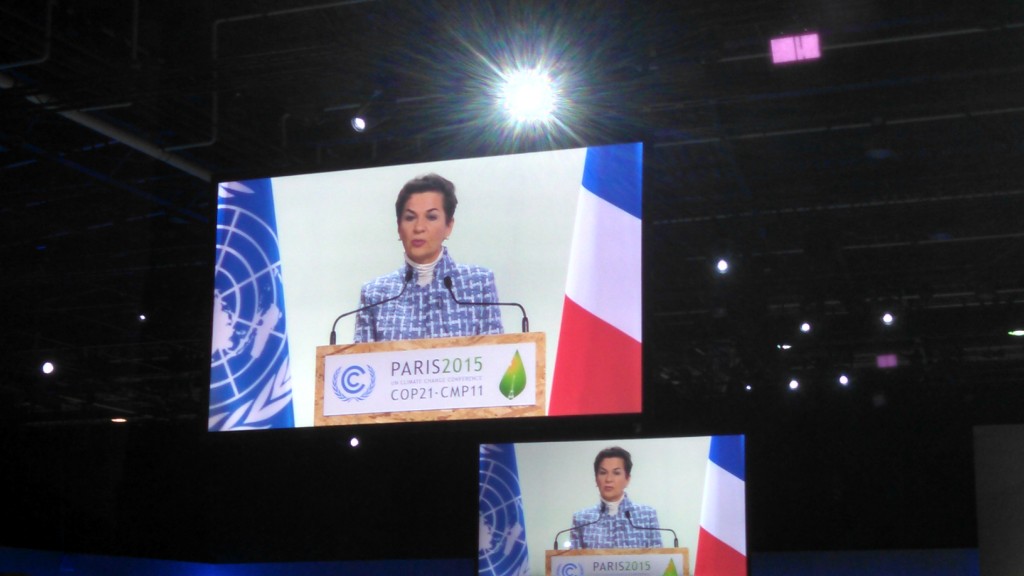

We kicked off the second week of negotiations by attending the Joint High-Level Segment of the COP21/CMP11, which included both pledges and statements of views by governmental ministers and other high-level officials, including UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and Swarthmore alumna, UNFCCC Secretary General Christiana Figueres.

Ban Ki-moon urged delegates to heed growing calls from civil society for ambitious action on climate, citing the 800,000-strong global Global Climate March during the COPs opening weekend and the $3.4 trillion in funds divested from fossil fuels. He went on to say: “Outside these negotiating halls, there is a rising global tide of support for a strong, universal agreement. All of us have a […] duty to heed those voices.”

Figueres echoed this sentiment, emphasizing the presence of “unprecedented mobilization” for climate action. She went on to say: “The challenge we face now is to crystalize that call into a cohesive legal framework that brings the world together in action and implementation.”

Christiana Figueres addressing the High-Level Segment

In addition to the remarkable support coming from civil society, there is also an unprecedented mandate for action amongst heads of state this year. Last week, the leaders of 150 different countries gathered at the COP for the first high-level segment. This format – with the heads of state initiating the conference but leaving before the negotiations reached full swing – reverses the set-up from earlier years. (In)famously, the 2009 talks in Copenhagen resulted in failure and embarrassment for many of the world’s leaders, who came at the conclusion of the conference but were unable to salvage the stalled deal.

This year’s change in format served the dual goal of avoiding further embarrassment while also galvanizing momentum for a legally binding agreement early on in the process. This tactic appears to have worked in generating will for the process before the “sausage making” by the political negotiators begins in earnest this week. Today, at the high-level segment, we repeatedly heard the ministers referencing the first high-level segment and the strong showing from heads of state.

During his remarks this morning, COP President Larent Fabius highlighted the newly formed Paris Committee, another recent addition to traditional COP protocol. This committee is an open-ended, informal grouping of all Parties that will aim to overcome differences in the production of a first draft of the Paris agreement by December 9. While observers cannot attend the Paris Committee discussions, in the interest of transparency, the Committee’s deliberations will be teleconferenced to other meeting rooms, so that observers can, well, observe. The emphasis on inclusiveness and transparency seems to be an attempt to correct past mistakes. In the past, negotiators have relied on the formation of exclusive, small groups that deliberate behind closed doors.

But even this year’s modified format is not immune from questions of fairness and inclusivity. Specifically, delegation size becomes a particular issue for informal negotiations, which pervade different aspects of the COP meetings. Since delegation sizes from the Parties tend to differ across richer versus poorer nations, the larger delegations have higher capacity at these negotiations (as well as in others). Despite the COP’s consensus based structure, there is by no means equality in representation and voice amongst the nations represented here. The next couple of days will make clear whether this inequity within the delegations will impede the emergence of a fair and just agreement.

– Anita Desai, Stephen O’Hanlon, and Ayse Kaya

Follow us throughout the week on Twitter (@SwarthmoreCOP21) and Snapchat (SwarthmoreCOP21) to get real-time updates.

Passing the torch

Indy and Dakota have done a great job of summarizing the current situation in their latest post, so I encourage you to read that. Now that I’m back at home, I just wanted to add my voice in welcoming our Swarthmore colleagues Prof. Ayse Kaya, Anita Desai, Stephen O’Hanlon, and Nathaniel Graf, who are arriving in France this weekend. I look forward to their news and insights over the coming week.

And this week promises to be exciting. To use the phrase that I heard several times in the past few days, this week “the ministers arrive,” the higher-level officials with more power to make meaningful concessions and hammer out the final agreement.

I’ve really appreciated the chance to share my experiences with you this past week, and I may yet have a post or two to share as I continue to reflect and take in the events of this coming week. I remain optimistic about the outcome. I had the good fortune of hearing former Vice President Al Gore speak on Friday, and he expressed his optimism with a quote from one of my favorite poets. It really resonated with me, so I’ll let Wallace Stevens have the last word:

After the final no there comes a yes

And on that yes the future world depends.

Where does the US delegation stand at the COP21? By Dakota and Indy

Approaching the halftime of the negotiations, there is a distinctive spectrum of perspectives visible from within the US delegation. On one hand, the youth delegation from the US is very optimistic and impassioned, taking the initiative to cooperate on actions with youth representatives from around the world as part of the YOUNGO youth constituency, trying to push for the US to take bigger and bolder commitments in terms of emissions targets, financial contributions, and overall willingness to commit to the hopefully binding legal agreement that is still in the works. On the other hand, the negotiation-facing side of the US delegation has had to deal with a far less progressive reality, mainly because of a much different type of climate problem back home.

Although President Obama has come to Paris seemingly committed to take action on preventing climate change, he still has to defer to the approval of politicians at home. If a legally binding text were produced as a result of the COP21, it would need a supermajority (⅔ of the total members) from the Senate to be able for President Obama to sign it into law. Given that there is currently a Republican majority within the Senate that definitely doesn’t think of climate change as an important topic (or in some cases, a reality), the chances of the US signing a legally binding agreement are ostensibly low. Additionally, the US made a pledge of $3 billion towards the Green Climate Fund in November, but that pledge may not be realized for similar political reasons. To that end, there have been rumors/accusations that the US has been using delaying tactics, slowing down the talks, and trying to push the negotiations away from a legally binding agreement towards a more provisional text that can be ratcheted up over subsequent years. Coming into the talks, the US was prepared to settle for a legally binding 5-year review, but is in limbo about the other conditions.

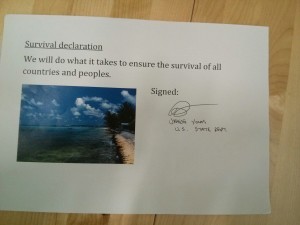

To engage with the delegation, we participated as youth representatives in an action organized by the Australian Youth Climate Coalition. Young participants from all countries were supposed to ask their national party negotiators at COP to sign a declaration to support the Climate Vulnerable Forum and small island states with their demand of a 1.5 degree target warming. The declaration had these words: “We will do what it takes to ensure the survival of all countries and peoples.” If the leaders agreed to sign they received a placard that they could use in the plenary saying “survival is our priority.” As the only US people interested we were given the seemingly impossible task of entering the US control booth with the bold proposal. After practicing our elevator speech a couple times together we approached the booth. As we tried to find a suitable delegate to ask to sign the pledge, we had a couple of run-ins with staff members who seemed to be somewhat dismissive of our purpose. They attempted to get us to come back later, but we insisted that it was youth and future generations day and that we needed our representatives to hear our voices that day and eventually our persistence paid off. We were finally introduced to Jesse Young, a senior advisor at the U.S. Department of State. He was genuinely interested in meeting youth. He listened to our spiel and then, to our amazement, ran back in his office to grab a pen to sign it.

In addition to signing the pledge, Jesse also gave us a quick, but thorough rundown of how the negotiations were proceeding which we have boiled down into these main points:

The negotiations are going more slowly than expected but progressing, although there is some frustration among the delegates.

Laurent Fabius, President of the COP21 has asserted that he wants to complete the draft version of the Paris agreement by next Monday so that the rest of the week can be spent refining the text before the closing of the COP sessions

The US is now supporting the addition of a Loss & Damages section in the text, which is historically unprecedented in the COP negotiations

At 6pm this Saturday the ADP (Paris Text) was closed. This means that there can be no longer additions to the current 48 page document, just deletions and removal of brackets. This seems quick, but yet again this text has been in the works for years. A liaison to the COP president reported today that the most important issues to resolve next week include: equity and differentiation. Finance remains the main sticking point, however. The hope is to tackle the most difficult issues first. There has been surprising progress, however, in regards to loss and damage as well as pre-2020 climate action. Saudi Arabia and Venezuela remain unflinching when talks threaten their oil profits. They have both opposed decarbonization in the negotiation space. With hardly any break, higher level negotiating sessions will start Sunday afternoon.

And that concludes week 1 and our time at the COP21. Tomorrow morning, we head back to Philadelphia, passing the baton on to the new Swarthmore delegation (Professor Ayse Kaya, Stephen O’Hanlon, Anita Desai, and Nathan Graf). As we head back to Swat, we are eager to continue keeping up with the proceedings and hearing about how week 2 unfolds.

Au Revoir,

Dakota & Indy

Surprise meal #2 with a party representative

Last night I dodged into a restaurant on my way back to the hostel following a long day at the negotiations. At a pretty far metro ride from the venue I was expecting to be finished with learning about COP for the day. Little did I know I was just getting started.

A party representative from Comoros took the open chair beside me. Between cigarette puffs he told me about his views on the climate negotiations.

How many years had he been going? “Since before you” was his simple response. Sure enough he had attended the 1992 Rio Earth Summit at the very beginning (2 years before I was born) and every COP since.

His answer was also concise for the largest climate worry for his country. “Sea level rise. We are an island and we will go under.”

Desperate for a glimmer of hope I pressed on asking if he thought young people had any influence or power at the negotiations. No, he said. As long as polluting countries, especially the US and China, are refusing to abate a considerable amount, nobody has much power.

Interestingly while the Comoros representative had little faith in a legally binding commitment in Paris, he had his eyes on Marrakech, Morocco (the location of COP22). His reasoning: even though Obama is intent on making a lasting agreement in Paris, the current US congress is not. After a new US president is elected next year the politics of the US congress will likely shift to being more serious about a climate commitment.

I left dinner with the weathered negotiator feeling pretty discouraged. These feelings of great hope and great sadness are both common here at COP when discussing the fates of current and future generations.

What negotiating looks like

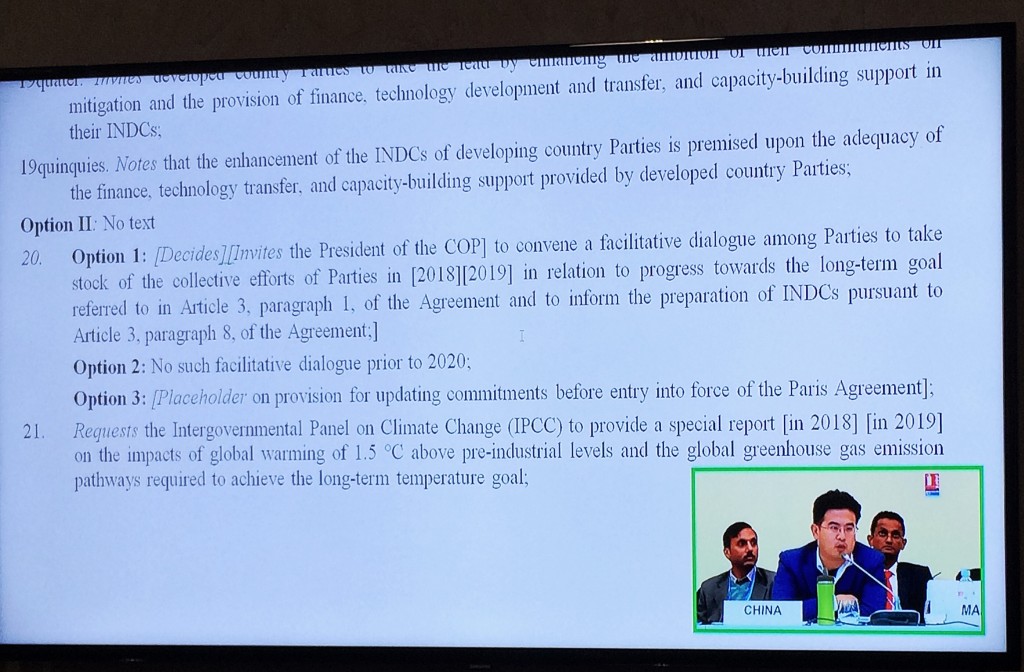

We’ve talked about “the negotiations” a lot, but what are the negotiators actually doing during those hours that they spend behind closed doors? They’re talking about language. I got a chance to see that first-hand (albeit at a slight remove) today. I was in a hallway in the building where most of the negotiations are taking place, and one of the video monitors in the hallway was showing a feed from one of the rooms. Mostly the video was of individual country delegates speaking, but briefly it showed the image above, display the section of the agreement text that presumably was the subject of current discussion.

At first glance, it looks pretty dull—most of us have edited texts before, and sometimes argued over wording details. But if you look closely at the paragraphs above (which are on page 28 of the new draft text released this morning), and think about how things differ if one option vs. the other is chosen, some of these things really make a difference in outcomes. Text in brackets indicates different possible wordings (per the U.N. editorial conventions), so if you look at Option 1, there’s a big difference between choosing “Decides” (it will really happen) vs. “Invites the President of the COP” (might or might not happen, depending on what the President does). And either of those is pretty different from Option 2, where it’s certain that nothing will happen before 2020.

And what’s happening (or possibly not happening) here is “stock-taking”, getting together to assess progress, and possibly increase effort, toward the goal of decreasing future warming. And what precisely is that goal (“referred to Article 3, paragraph 1”)? It is—you guessed it—still being negotiated, but it reads in part (after referring to yet a different article and paragraph):

“Hold the increase in the global average temperature [below 1.5 °C [or] [well] below 2 °C] above pre- industrial levels by ensuring deep cuts in global greenhouse gas [net] emissions;”

Clearly there is [work still to be done] [progress still to be made] [drama ahead]—stay tuned.

Too fast, or too slow?

Animals from “Noah’s Ark of the climate”, by artist Gad Weil, on display here at COP21.

Animals from “Noah’s Ark of the climate”, by artist Gad Weil, on display here at COP21.“The pace has been slow and we have many issues that remain unresolved.”

“…progress was too slow.”

“We need a change in the mode of work.”

“The parties have engaged actively… but the pace, in my view, is nowhere near fast enough.”

“The parties have expressed clearly… support for transparency. Like others, the pace is not good enough. We will continue to work tonight.”

One after another, thus went the summary statements about the negotiations from the facilitators of the various groups. This was part of an update last night on the progress of the negotiations so far. It was attended by the lead negotiators of the various countries, as well as the COP President. As you can see, there was a consensus that not enough progress is being made toward the goal of having an agreed-upon text by noon on Saturday.

After the updates from the facilitators, the chair of the meeting opened the floor to the individual country representatives who were present. At that point, the tone and focus changed dramatically. The ambassador from South Africa, speaking on behalf of the G77 (a coalition of developing countries) and China, expressed “some concerns with the process.” She spoke of the proliferation of spinoff and informal discussions, sometimes on the same issue and taking place simultaneously. She also noted that sometimes these were announced at the last minute, and asked for better advance notification of schedules.

In addition to concerns about scheduling, she made some specific requests on behalf of the countries for which she was speaking. One concrete request was for the UNFCCC to compile the various edits that had been produce so far in the various negotiating groups, and to produce a new master (but still provisional) text that would be made available to all parties in the morning. I assume that the goal of this was to allow them (and everyone else) to get a better sense of where things stand, since issues being discussed in one part of the text will have impact on other parts of the text. (The chair of the session later agreed to this request, and the new text is out this morning.)

After South Africa spoke, the representative from Malaysia spoke, saying that he was speaking on behalf of like-minded developing countries. He said that he supported everything in the previous statement, adding that the pace of the negotiations was “punishing.” As an example, he cited three parallel processes on mitigation taking place in three difference rooms. He said, “We cannot sacrifice a durable agreement at the altar of expediency,” saying that some of the countries were beginning to feel left out.

Apparently this is a perennial problem at the COPs. The smaller and/or less-developed countries have smaller delegations, and thus it is harder for them to have a presence at multiple sessions taking place simultaneously, and to keep up long negotiations that can stretch well into the evening hours. In fact, some of the observers who are here come to COP specifically to help smaller states navigate the process, so that they have extra bodies to track what is going on in various parallel sessions (though observers have much less access than party delegates do).

I don’t have the experience to gauge whether these concerns are worse at this particular COP, given the urgency and the relatively short deadline of trying to agree on a provisional text by Saturday, and how much this is viewed as part of the process. But having read about this before the COP, it was interesting to see it playing out in real time.

After these statements, several other countries were given the floor to make statements. One interesting bit of procedure that I noted: it appears that parties request the floor by turning their country nameplates on their side, so that they are sticking up in the air. (You can see this in the photo above.) I couldn’t see everything that was happening (we were watching on closed-circuit TV from another room), but everyone who spoke had an upended nameplate, and they put it back down when they finished speaking, so this appeared to be what was going on.

Some of the remaining discussion amounted to parties saying to each other, “No you need to be more flexible,” albeit in a diplomatic way. Other countries weighed in with additional comments on the fast pace or the need for progress.

The final statement came from the representative from Mexico, who said, “We have talked about urgency for a long time, but this is the place to show it.” The negotiations are continuing today, and it will be interesting to see whether the collective sense of urgency produces more progress.

The Story of Tuvalu

Today, I started out the COP by attending the YOUNGO meeting and then heading over to a press conference held with the Prime Minister of Tuvalu, Enele Sopoaga because I wanted to get the live opinions on the negotiations from a Head of State. Tuvalu is one of the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) that has a population of just over 10,000 people and around 10 sq miles of land area. It is also especially susceptible to changes in sea level as well as storms and typhoons because of its low lying land-mass (just 15 ft above sea level) and a major concern is that sea level rises will cause Tuvalu to become inhabitable and potentially even force relocation of its citizens in the coming decades. With this background in mind, I settled into a seat near the front and pulled out the camera to record what I anticipated to be an thought-provoking speech. I was not disappointed, and there were a lot of memorable statements to be recounted.

After making a round of introductions to other dignitaries in the room, Enele got straight to the point. “Tuvalu is suffering.” He reiterated that a 1.5 degree Celsius cap was essential for the survival of the islands. He then pushed onto the negotiations, citing his support for a legally binding agreement to come out of the COP and sticking a point in to the Loss and Damages discussion about how if framed properly there would be a wider agreement between parties on this matter. “This is not about loss and damages, this is about survival.” was Enele’s reply and an adequate one I think for the PM of an island nation. He then moved on to discussing how he felt things were moving along at the negotiating table, and this next statement sums things up quite adequately. “The process has been very slow, very (un)transparent, and there’s a lot of twists and turns that small nations like Tuvalu cannot follow because of logistics. And that defines a very unjust process already.” This was followed by an even stronger statement about the impacts of political foot-dragging, “There is always a tactic of delaying until the last minute, and then being dumped upon, by something that is totally weak and is not worth the paper it is written on as we saw in Copenhagen.” Bang, no beating around the bush. Enele continued on, asking other parties not to utilize this as a tactic even citing the US as a culprit in dragging down negotiations and appealing directly to COP Presidency followed by another call, specifically to the leadership of the EU (Germany and the Netherlands in particular). for a legally binding solution and cooperation on loss and damages.

He then voiced his desire for mechanisms that include regular and consistent reviews of the actions of their parties to meet their INDCs and mentioned Tuvalu’s impressive commitment to switch to 100% renewable energy by 2020. He then alluded to the Kyoto Protocol as a cautionary tale for the Paris agreement, finishing up this portion of his speech with another call to not hit a dead-end like in Copenhagen.

Finally, Enele switched gears to talk about financial mechanisms and their impact (or rather lack of impact on Tuvalu). Labeling the current situation as “unforunate” the Prime Minister described the inability of low-resource SIDS such as Tuvalu to submit sound, and scientifically justified proposals to obtain funding through UN sources such as the Green Climate Fund. “Bureaucracy is taking over. Not the parties. The parties that need resources such as the Green Climate Fund are being neglected.” He followed with a call for parties to do away with such “conditionalities” and to consider the vulnerability of nations rather than the quality of their proposals. Lastly, Enele used the CDM as an example to make a pitch for renewable sources of funding to be added to the current financing mechanisms so that money is not simply being siphoned off to the abyss of climate financing and that Least Developed Countries (LDCs) who have contributed the least to climate change are not continually being forced to finance their own adaptation which he labelled as a final “great injustice”.

It was hard to hear from Enele that the talks were still too slow to keep up with the demands of SIDS, but his talk inspired some hope in me. If a country as small as Tuvalu can put forth so much effort to push for change and still keep up hope despite being completely disadvantaged, it stands to reason that the US should have no reason to drag its feet. As a representative from a large, well-funded, and well-equipped delegation, this talk made me rethink my perspective on what needs to happen here at Paris. Having an SIDS perspective was really invaluable, and it is really important to keep these vulnerable countries in mind moving forward. Their voices matter too.

Briefing by the COP President

Professor Jensen, Dakota, and I all attended an observer briefing today by the President of COP21. As per tradition the position of the President is held by a high-ranking official of the host country. In this case Laurent Fabien is the French minister of Foreign Affairs. For these two weeks his duties include chairing the Bureau and COP Plenary, proposing compromises in the Paris Agreement text, and providing political leadership. Each year the President strikes his or her own balance between staying impartial or promoting his or her own agenda. We were interested in this briefing because the procedural fluency of the President can have a large impact on the result of the negotiations.

We were first struck by Fabien’s affable demeanor. He emphasized that we, the audience (consisting of delegates from observer organizations), have a major role as both observers and actors. He spoke directly to the people who asked questions with thoughtfulness while occasionally even inserting jokes. He was also self-deprecating: “I am a student trying to learn quickly.”

The second thing that struck us was Fabien’s deliberateness in setting the stakes high for Paris. “There will not be a better opportunity than now.” He said that COP21 is our last chance to make something big happen with regard to global emissions cuts, and if we can’t get an agreement now, the whole procedure should be under question.

Fabien, along with the previous COP20 President and Peruvian Minister of the Environment Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, fielded questions from multiple observer groups such as environmental NGOs, the trade union, and youth NGOs. Fabien made it clear that personally he is in favor of keeping equity language in the Paris Agreement such as human rights, long term goals, loss and damage, and differentiation. However, he said that he hoped that he would have some influence on these topics, but also that his power was limited and he would mostly remain neutral in his role as President. Fabien was not helpful about the floor questions over transparency and better accessibility to meetings. He merely said that France was following the rules.

What surprised us the most was when Fabien stated that he was committed to having a text of the ADP (aka the Paris Agreement) by this Saturday, the 6th of December. This way there would be a whole week for deliberation and discussion on the text. Fabien hopes that the new text going into week 2 will be shorter and have fewer brackets—meaning less to argue about between parties. He wants to finalize the draft by Wednesday, December 9th, so that there is not the usual chaos that ensues at the final gasps of the negotiation.

The COP21 president sounds hopeful about the international legal agreement in the middle of week 1 of the negotiations. We shall see if the optimism continues and whether climate justice does in fact remain in the text.

That’s all tonight from Le Bourget!

Bonne Nuit