Tonight, as the Malaysian minister declared to a vast conference room packed full of people, “everybody seems unhappy.” As the third-to-last day of COP-21 came to a close for observers (negotiators will remain at le Bourget longer into the night), the prospect of an ambitious agreement seemed tenuous. Despite the fact that the new version of the draft text released today boasts a ¾ reduction in square brackets (though, some delegates remained unhappy about the deletions), serious disagreements remained amongst the parties.

Let’s rewind to earlier in the day. In the morning, observer groups, ranging from BINGO, to RINGO, to indigenous peoples’ organizations, got a chance to have a briefing with Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC, Christiana Figueres, as well as H.E. Minister Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, President’s Special Envoy to Observers at COP 21/CMP 11. Vidal served as President of COP 20 and is here in Paris as both the minister of Peru and the conference’s envoy to civil society. Throughout the briefing, various organizations voiced their discontent with the lack of access to negotiations given to civil society. Participants were clearly concerned with finance and differentiation, among other issues, but felt that the meetings lacked transparency and an appropriate avenue for them to voice their concerns. In a candid response, Figueres said that this COP outcome will be a fundamentally “intergovernmental agreement,” and that, in the end, it is the national parties who will have to reach consensus. However, she guaranteed the observers that the agreement “is not going to be moving into the direction of national interests,” but instead will “be moving into convergence, onto common ground.” Yet, despite the discontents voiced, there were also moments of laughter and applause. For instance, when Figueres received presents from one of the indigenous people’s groups (see picture), the room broke into applause. The group presented her with gifts as well as a message, “we must all grow in the same direction.”

Then, at 3pm, we received the first draft text of the Paris agreement in a meeting that lasted about five to ten minutes. Observers, and other non-Party participants of the conference, could get the text right after its release from the “Documents” booth. We wish we could have taken a picture of the chaotic crowd clustered around the booth with hands sticking up in the air for a copy, but we were a part of the crowd with no free hand for a picture!

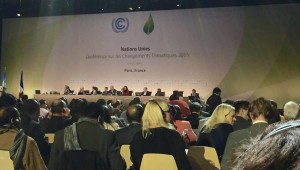

Now the Parties (and everyone else) had time to study the text, consult with their groups and others, and reconvene at 8pm, for tonight’s Comite de Paris meeting (Paris Committee – see our earlier blog).

At tonight’s session, which lasted until about 10:30 pm, many countries’ interventions expressed forceful and seemingly irreconcilable viewpoints on the future of the agreement. Once again, the G77 + China maintained a strong presence/support base amongst the speakers. The minister from South Africa spoke first as the representative of this group. She outlined the substantial work that still needs to be done with regard to differentiation, adaptation, implementation, capacity building, and loss and damages. Other developing and least developed countries echoed her statement and added additional concerns. A common theme within their interventions was praise for the strong language supporting a 1.5 degree goal, but a fear that this goal will be futile without the appropriate implementation and financing mechanisms. As the representative for Venezuela noted, the current INDCs allow temperatures to rise to 3+ degrees from pre industrial levels. Without more substantial contributions, an agreement on 1.5 degrees would be rendered meaningless.

In stark contrast to the G77 + China was the Umbrella group*. The Umbrella Group was represented by Australia, whose delegate expressed frustration at the lack of balance in the draft agreement. The group seems to feel that their acquiescence to the 1.5 degree goal warrants significant concessions from developing countries that have not yet been made. For example, one huge issue is how stringent the monitoring, reporting, and verification of the mitigation commitments should be, with countries like China preferring to retain sovereignty over reporting, while others, like the EU, pushing for a review every five years.

Notably absent from tonight’s proceedings was the voice of the United States. Although the U.S. is a member of the umbrella group, our negotiators themselves remained silent throughout the meeting. Earlier in the week Secretary Kerry stated that the U.S. would be willing to support the 1.5 degree goal, so long as other countries were willing to compromise on loss and damages. But tonight, neither issue was addressed by our delegation. Whether or not this was an overt statement of dissatisfaction with the course of negotiations, not having the USA participate in an almost universal discussions of the new draft of the Paris agreement was disheartening and surprising.

In all, tonight’s events struck us as a diametric shift from the positive tenor of yesterday’s Comite de Paris meeting. This COP has been applauded as calm, orderly, and polite in comparison to other conferences. But as some of the delegates spoke, their exhaustion, exasperation, and sadness was palpable. We could clearly hear two divergent tones coming from the speakers. From some (the EU, Japan, Australia and others) came a terse dissatisfaction with what they have found to be intransigence on the part of many developing countries. However, these and other more procedural interventions were punctuated by sincere pleas for swift and ambitious action from many countries (particularly Small Island Developing nations, or SIDs). The minister from Barbados, for example, said that he was “not here begging for sympathy,” but that inaction on climate change would mean the “certain extinction of [his] people.” For those most vulnerable, the fate of their countries still rests within square brackets.

There is very little time left and many differences to be ironed out. Hopes are pinned on two long nights.

-Anita Desai, Stephen O’Hanlon, Ayse Kaya

Follow us throughout the week on Twitter (@SwarthmoreCOP21) and Snapchat (SwarthmoreCOP21) to get real-time updates.

*From the UNFCCC site: The Umbrella Group is “a loose coalition of non-EU developed countries which formed following the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol. Although there is no formal list, the Group is usually made up of Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Kazakhstan, Norway, the Russian Federation, Ukraine and the US.”