By Prof. James Padilioni, Jr.

Como arena entre los dedos. For some reason, there are certain phrases that strike me as more evocative in my heritage language of Spanish than their translation into English, my dominant tongue. One of these – como arena entre los dedos / like sand between the fingers – describes the futility of exerting more and more energy trying to accomplish something that is fundamentally structured in an antagonistic or unproductive way.

For the last week I have attended side events, plenary sessions, and policy negotiations at COP28, and despite the goodwill for building sustainable futures carried to Dubai Expo City by many of the over 80,000 registered attendees, all I keep hearing in my head is the endless refrain that so much of the intentions uttered here will amount to nothing more than a Sisyphean effort to grab hold of the earth como arena entre los dedos. Though I strive to model for my students that “my default position is wonder [in the face of the beauty, magic, miracles, and patterns of the world], I am not without critique, disappointment, frustration, and even depression when I contemplate humanity.”

Since the 2015 adoption of the Paris Agreement, much fanfare has been made around the target of slashing emissions by half their current rate prior to 2030 in order for humans to have a chance at limiting global average temperature warming to only 1.5°C beyond pre-industrial levels (with a 2.0 degree average warming placed as the upper threshold of acceptability.) However, report after report issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the World Meteorological Organization, and other climate science researchers over the course of 2023 in advance of COP28 has continued to sound the alarm that, with our current carbon emission rates, Earth is likely (66%) to exceed the 1.5°C benchmark prior to 2030, despite the now-eight-year global campaign to mitigate this outcome. Additionally, since the 2015 adoption of the Paris Agreement, it has also been known that COP28 would form the first global stocktake, defined by the UNFCCC as “a process for countries and stakeholders to see where they’re collectively making progress towards meeting the goals of the Paris Climate Change Agreement – and where they’re not.” As an accounting and inventorying measure, the global stocktake was intended to enable the world to “identify the gaps, and work together to chart a better course forward to accelerate climate action.”

But I am pained to report the global stocktake is, perhaps, the grandest staging of political theater humankind has ever had the opportunity to witness. For eight years now, various carbon markets and other trading schema have emerged to help facilitate a country’s net reduction in fossil fuel emissions so they can meet their obligations according to their nationally determined contributions (NDCs). But, at best, this stocktake is a ruse that, como arena entre los dedos was never intended as a true or accurate accounting measure, as country NDCs and their concomitant stocktake do not account for carbon emissions generated by militarism and warfare. Here, I find myself once again turning to sand as a proverbial figure for human futility: how utterly absurd it is to speak of reducing carbon emissions while simultaneously sticking one’s head in the sand as it relates to the ecological cost of warfare writ large. One cannot claim to care about the environment on one hand, while ignoring a primary vector of environmental degradation on the other. To ignore military fossil fuels on paper, while espousing “net-zero” carbon arrangements via financial and credit instruments is the height of absurdity. The reality of our warming atmospheric condition abides, regardless whether we factor military greenhouse gases into our bookkeeping measures or not.

From the Steppes of Eastern Europe to the Levant of the Eastern Mediterranean, and down through the Sudd wetlands of the Upper Nile to the Jebel Marra and beyond, the ecological destruction of warfare is on full display as we “doom scroll” through our social media feeds. As The New York Times has made clear, it should be obvious to any half-aware person that “Wars destroy habitats, kill wildlife, generate pollution and remake ecosystems entirely, with consequences that ripple through the decades.” But that which is seemingly-obvious is often elusive to collective human efforts, and thus, while the UNFCCC climate regime seeks to reign in excessive carbon emissions, warfare and genocide form the durable, though apocalyptic, signs of our times. Since February 2022, the Russian-Ukrainian War has expended over 150 million tons of carbon, or “more than the annual emission of a highly developed country like Belgium” according to Viktoria Kireyeva, Ukraine’s deputy minister of environmental protection and natural resources, who addressed this matter at the COP28 side event, “Climate damage of Russia’s war in Ukraine and the knowledge gap on conflict and military emissions COP28.” Likewise, in just the first month of Israel’s besiegement of Gaza, over 25,000 tons of munitions rained down upon the coastal strip the size of Philadelphia, with a carbon expenditure equalling the “annual energy use of approximately 2,300 homes, or the annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from approximately 4,600 passenger vehicles.” And even in so-called peace time, the world’s militaries, with their aircraft, tanks, and weapons, and via their drills, exercises and other daily operations, are estimated to account for 5.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Of course, this is only an estimate because the Paris Agreement contains no operationalized mechanism to provide a true accounting of militarism’s carbon budget.

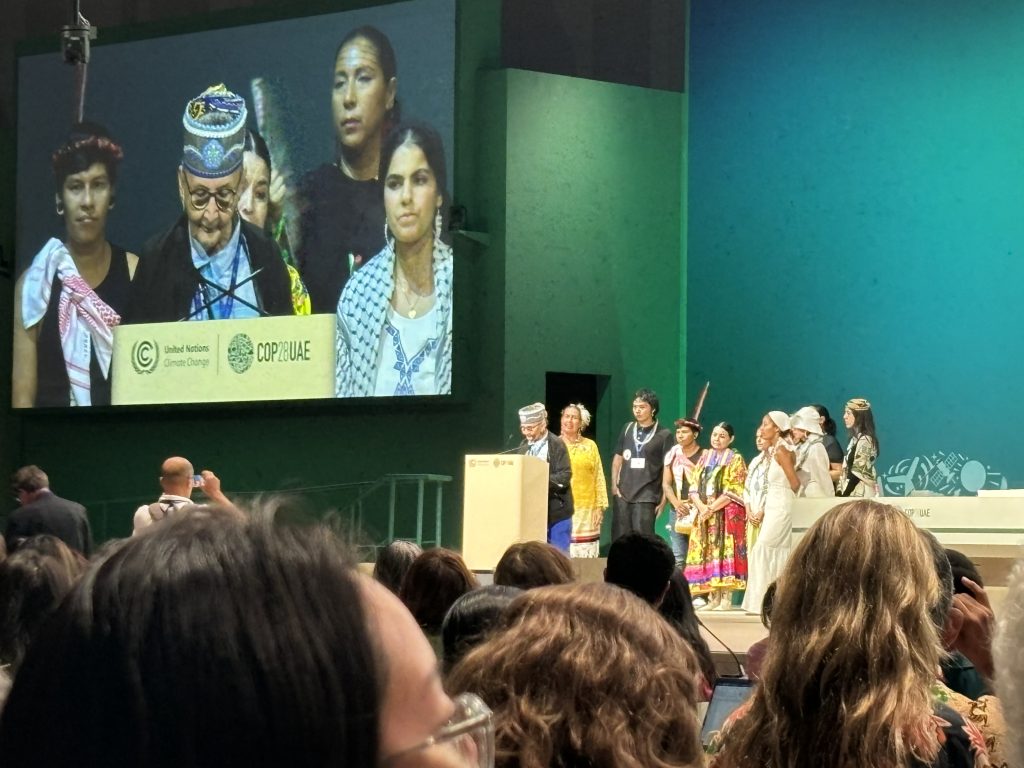

But this is not the whole story. Or at least, I refuse to accept that this be the whole story, for I am convinced that hope is the precondition of all social movements for justice. A young activist addressing the crowd gathered for the COP28 People’s Plenary evoked yet another metaphorical figure of sand and soil that also resonates with me more evocatively in Spanish than English, on account of the fact I first learned of this popular Mexican dicho while visiting the revolutionary murals of San Diego’s famous Chicano Park in Barrio Logan. Despite the seemingly-nonstop onslaught of bad news, we must never let ourselves feel beat down, but, rather, remember this truth: they tried to bury us, but they forgot that we are seeds / intentaron de enterrarnos, pero no sabían que somos semillas. While the shifting sands of time and the fog of war obscure our utopian visions for desirable sustainable futures, may we never forget our collective power to sprout, set roots, and flourish.