By: Emmy Li’25 (she/her)

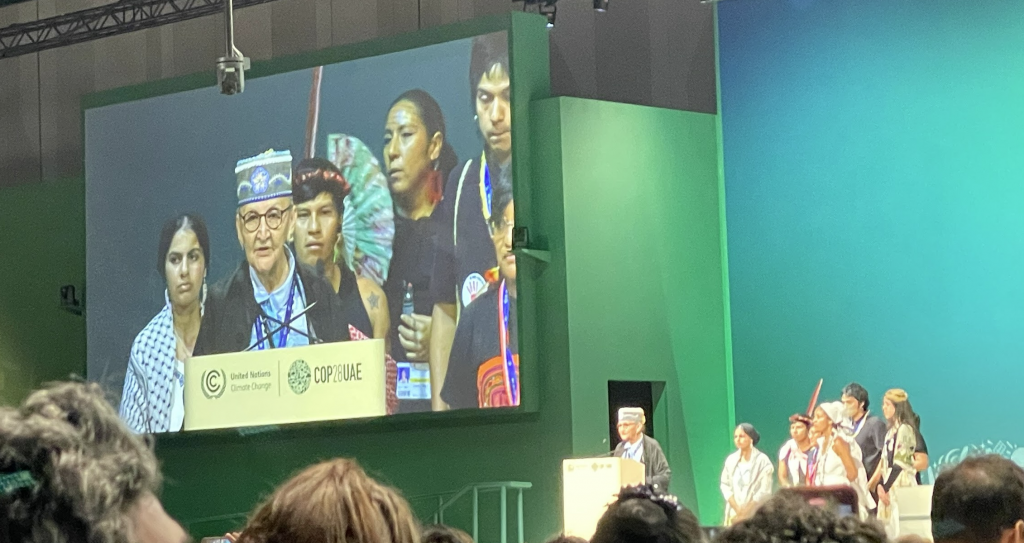

For the second year in a row, the Swarthmore delegation attended the People’s Plenary, a large gathering of civil society representatives making their voices and demands heard. Similar to COP27, this event was nowhere to be found on the UNFCCC COP28 Daily Programme schedule despite being an official UN sanctioned event. However, after learning of it in group chats, we officially marked it on our calendars and excitedly attended.

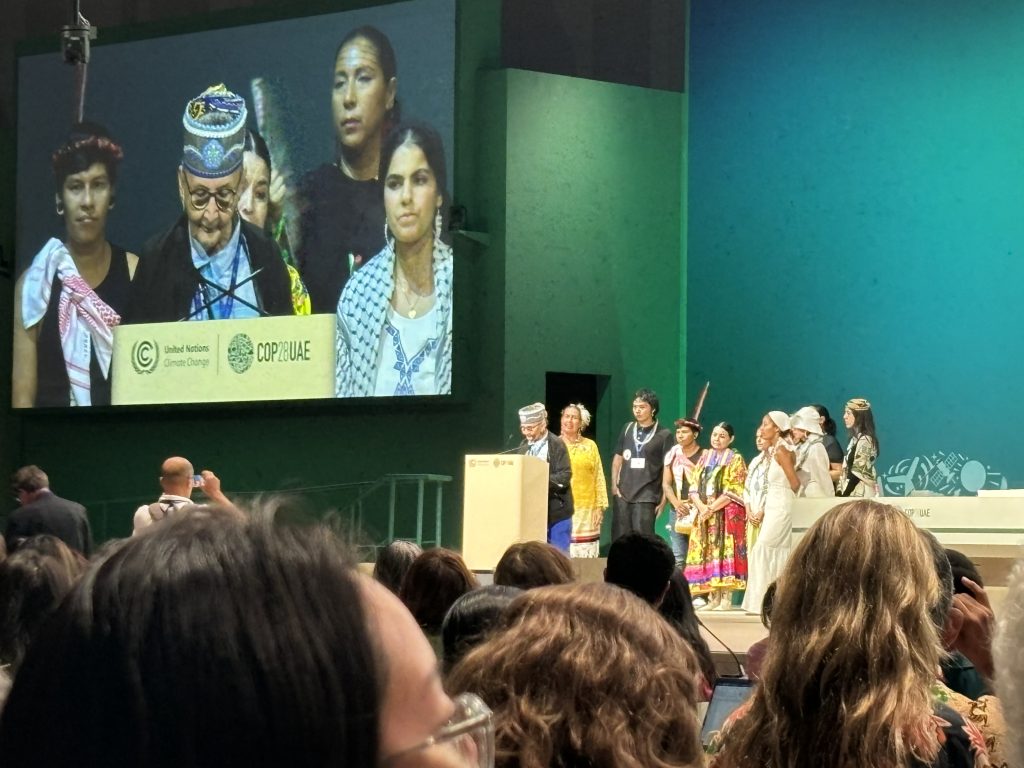

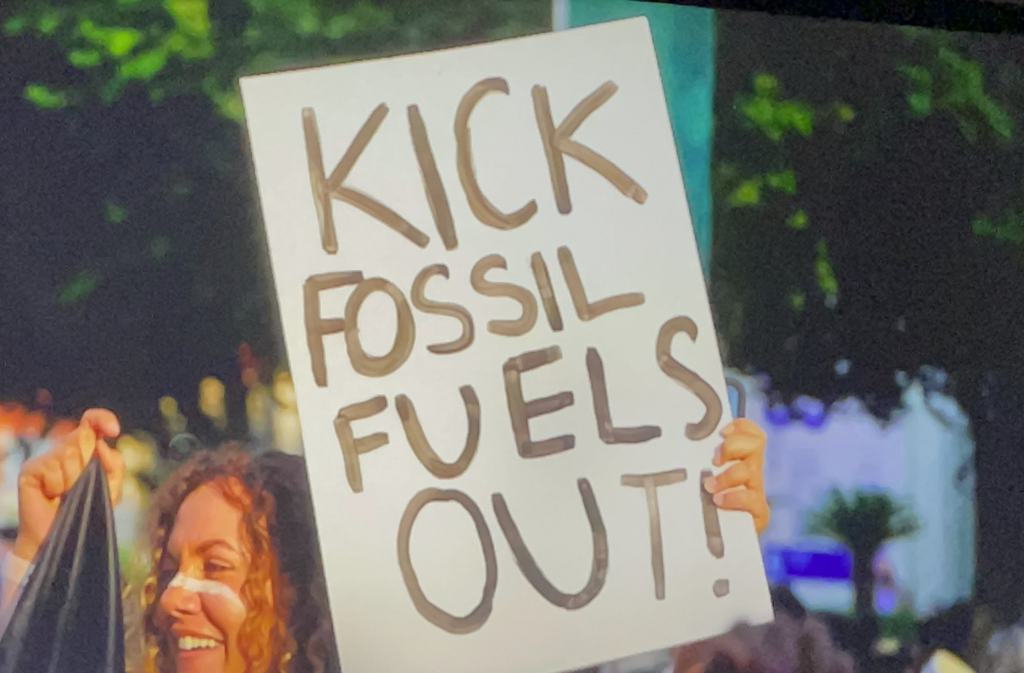

The People’s Plenary, by far, did not disappoint. After spending nearly two weeks sitting in on stalled negotiations or witnessing the constant greenwashing around the venue, it was rejuvenating to hear the voices of those fighting climate change on the frontlines. Representatives from Indigenous Peoples, youth, women and gender constituencies, environmental NGOs, trade unions, and farmers all came together to give impassioned speeches calling for real climate solutions – ones that recognize Indigenous rights, labor rights, land rights, and human dignity. Hearing their voices gave me hope that we will find real solutions to combat climate change. That eventual fossil fuel phase out is possible despite parties blocking it from happening in negotiations currently.

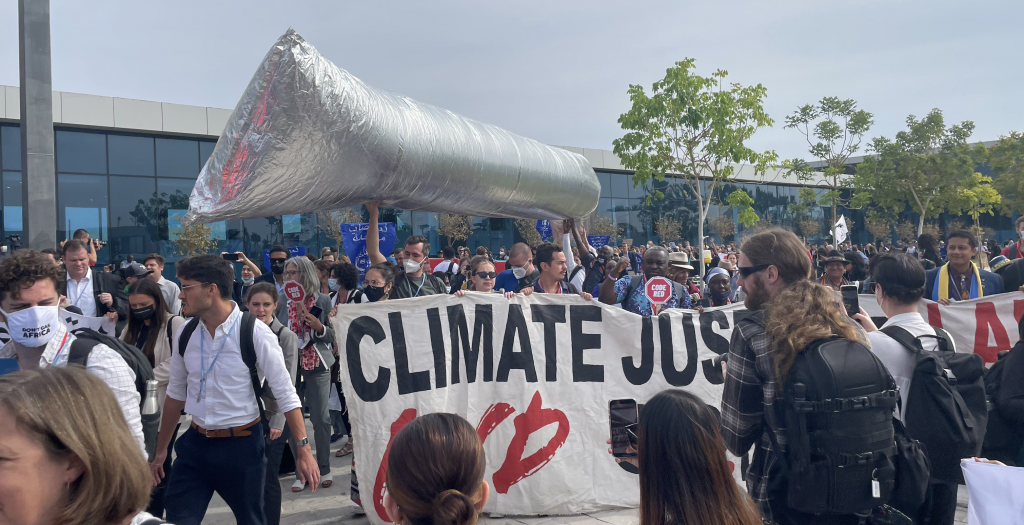

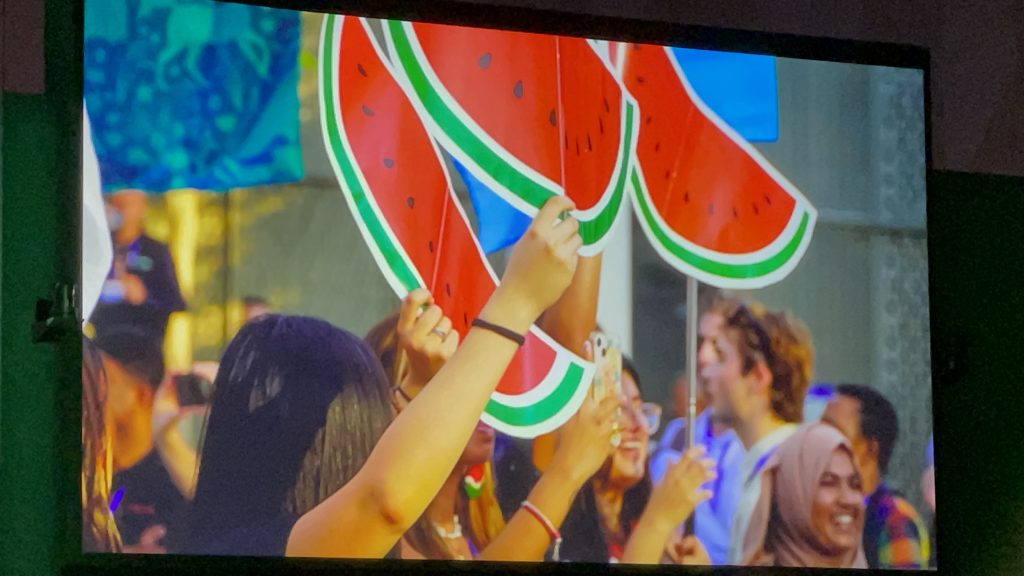

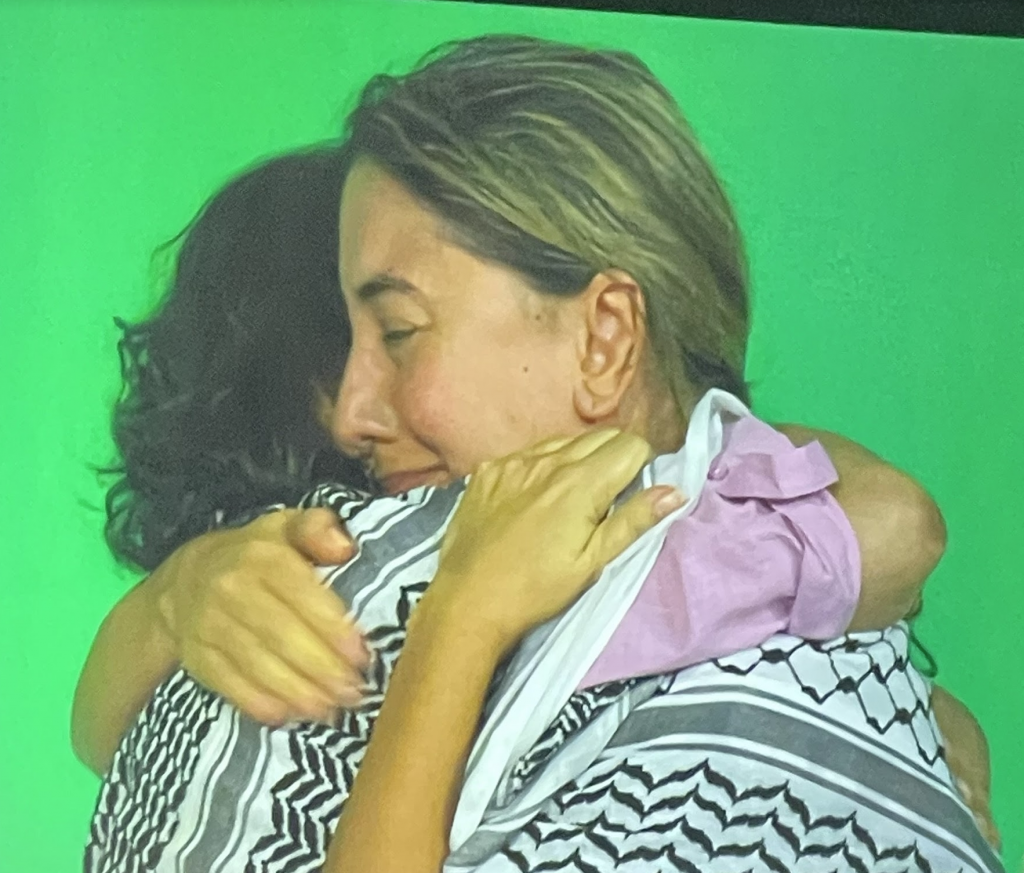

A noticeable theme across speeches at the People’s Plenary this year was a calling for the immediate ceasefire in Palestine. During the opening speech, the co-chair started by stating that she is from Palestine. Immediately, the whole room erupted into cheers of support and solidarity that continued for more than a minute. The calls for solidarity with Palestinians continued throughout the People’s Plenary, despite the regulations put in place by the UNFCCC Secretariat. I later learned from an organizer with the Climate Action Network (CAN) Australia that protests at COP28 are all strictly approved, controlled, and enforced. In regards to support for Palestine, protestors are not allowed to mention Palestine by name (despite the State of Palestine having a designated pavilion), cannot chant “From the River to the Sea,” and can only call for a “Ceasefire” but NOT “Ceasefire Now”. If protestors violate these restrictions, they risk having their badge taken away and being barred from attending COPs in the future. Despite these restrictions, those who spoke at the People’s Plenary asserted their voices to echo the overall theme that “there is no climate justice without human rights.”

Given the various moving speeches, I would like to take the rest of this blog post and dedicate it to sharing the voice of the people. Representatives from all across the globe emphasized their extreme frustration with the existing UNFCCC system, a need for a just transition, and an overhaul of the existing capitalist, exploitative system that causes marginalized BIPOC communities to suffer the most at the hands of rich countries in the Global North.

From the Co-Chairs of the People’s Plenary:

- “There is no climate justice, without human rights”

- “Ceasefire Now!”

- “What has Palestine got to do with climate change? It has everything to do with climate change! It is the very same system that is responsible for climate change and colonialism.”

From the Representatives of the Indigenous Peoples Organizations (IPO) Constituency:

- “I am the water and the water is me. I am the fire and the fire is me. I am the air and the air is me. I am the earth and the earth is me.”

- “You cannot put a price on humanity and nature.”

- “Earth, air, fire, water show no prejudice. Greed, greed created that.”

- “We are the regions [Global South] that have the most killings just because we defend our lands.”

- “When they talk about nature based solutions, we are part of the relationship with nature to engage in activities. We are the solutions.”

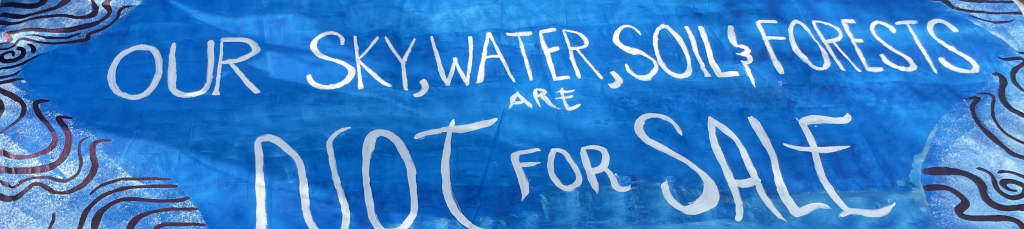

- “We should stop commodifying indigenous territories, Indigenous lands. We are not an economic resource for the system and we will fight towards the end.”

- “We are not here as passive observers, but experts, custodians of knowledge.”

From the Representatives of the Youth (YOUNGO):

- Naomi, a 13 year old girl from South Sudan:

- “I come from a country where children’s rights are being deprived because of flooding.”

- “We’ve attended 28 COPs but nothing has been implemented from what we speak.”

- “If there was action, children wouldn’t die in rural areas, there wouldn’t be hunger in places.”

- Roa, a youth from Sudan:

- “An error does not become a mistake until we refuse to correct it.”

- “If we don’t work together to save the environment, we will be equally extinct.”

From the Representatives of Trade Unions (TUNGO):

- Joy Hernandez, a trade union worker in the Philippines:

- “There is no just transition without labor rights.”

- ”A just transition must be an opportunity to uphold our dignity.”

- Bert Del Wel, the head of TUNGO:

- “A just transition is about solidarity and justice. It’s about a decent life and jobs for everyone and everywhere. It’s about justice in and for Palestine. It’s about cooperation and support for equality and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

- “We need organized workers. We need collective bargaining, social dialogue, and a social protection system to deliver this climate justice.”

From the Representatives of FARMERS Constituency:

- “We need protection of land rights, because land is the fundamental source of life.”

- “How many people at this COP talk about land as the source of everything we need. They talk about markets. They talk about oil. They talk about money. Yet land is where we are rooted.”

- “The agribusinesses that are here today trying to say that they provide the solutions to feeding the planet in the place of increasing climate chaos are not the ones providing the real solutions. The small scale farmers are.”

- “They thought they could bury us, but they didn’t know that we were seeds. And that’s exactly what small scale farmers do. They provide the seeds of the future. When you bury us, we will grow.”

From the Representatives of the Women and Gender Constituency:

- “There cannot be climate justice on occupied land.”

- “The elephant in the room is demilitarization.”

- “We are tired of being your bargaining chips.”

- “We call resistance. [Repeated in Arabic]. We call liberation. [Repeated in Arabic]. We call equity. [Repeated in Arabic].”

- “The silence and global north organization in positions of power is unbearable. The limitations on freedom of speech imposed in this space by the UNFCCC are left on the shoulders of the civil society movement is unacceptable and beyond paid for.“

From a Representative of an organization to demand climate justice:

- “La tierra no se vende, la tierra se defiende.”

- “Nobody is free until everybody is free.”

From the Representatives of Environmental NGOs (ENGO) Constituency:

- Tasmeen Essop, director of Climate Action Network and from South Africa:

- “The governments today are disappointing us and our Palestinians. But it’s the people across the world that are rising up and standing with Palestinians. That is our power. We will not let down our brother and sisters in Palestine, just like we did let down the people in South Africa”

- Speaker 2: Male representative from the Global Campaign to Demand Climate Justice:

- “Their broken promises on climate finance, on equity, and on justice litter 28 COPs. Their empty words no longer fool anyone. But our fight has never simply been about reducing carbon. Our fight has always been about ending injustice and inequity.”

- “Our goal is to uproot this rotten system and injustice of 500 years of exploitation and extraction.”

- “Our fight is not just about a just transition. We want a justice transition. Our fight is a fight for humanity.”

- “Yes, we say ceasefire now. Yes, we say end the occupation….And yes, we say we want an end to this rotten system. POWER TO THE PEOPLE!”

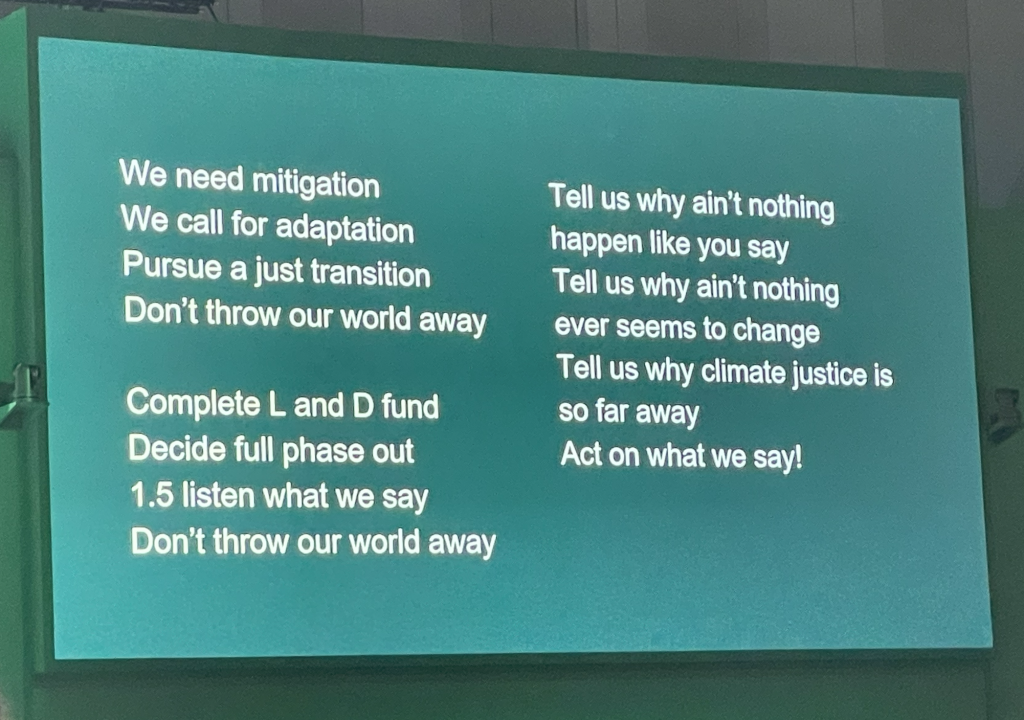

As the People’s Plenary concluded, the collective call for climate justice continued to echo through the halls of COP. We all marched out of the plenary led by youth activists to a climate parody of the Backstreet Boys’ song “I Want It That Way.” I hope that seeing, reading, and hearing these activists make you feel as empowered as I do for the future of climate action.