by Mahika Shergill ’26, Honors Economics & Environmental Studies

BAKU, Nov 15 – At the 29th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29), held in Baku, Azerbaijan, finance is taking center stage as global leaders, climate advocates, and representatives from the public and private sectors discuss ways to scale up financial commitments to combat climate change. Dubbed the “Finance COP,” COP29 has prioritized the mobilization of significant climate finance to meet the urgent needs of mitigation and adaptation. Central to these discussions is the establishment of the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance, intended to replace the previous $100 billion annual commitment made at COP15 in 2009.

The NCQG aims to recognize the enormous financial demands of effective climate action. Initial estimates suggest that climate action requires at least $1 trillion annually, with some projections reaching higher to meet ambitious climate goals. The NCQG not only sets a new target but also shifts the approach from a purely public-funded framework to one that encourages substantial private sector contributions — by the end of the two weeks, the COP Presidency and 198 parties attending hope to reach consensus on what this NCQG means for the climate and its people, and how much money will be committed to it.

As a junior studying economics and environmental studies with a particular interest in climate policy and law, I tracked discussions around climate finance and carbon markets during week one of COP29. Over the 25+ events and negotiations I attended over the course of the week, a key idea that was repeatedly talked about was the collaborative potential between governments, Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), and the private sector, all working to unlock the financial flows necessary for meaningful climate progress.

Cross-Sector Collaboration: Public-Private Partnerships as a Catalyst for Climate Finance

At COP29, the necessity of private finance for impactful climate action was a recurring theme. Public funds alone are insufficient to meet the vast investment requirements for a low-carbon transition; therefore, COP29 discussions frequently focused on how to engage private capital effectively. The NCQG itself aims to shift from a purely public-funded model to a framework that prioritizes robust public-private partnerships, emphasizing private sector participation as central to meeting climate targets.

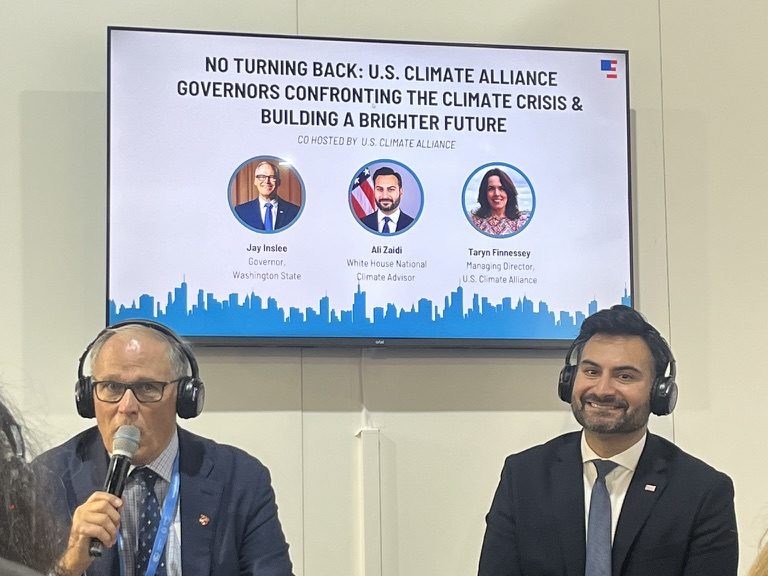

A key insight from the panels came from discussions on the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which has catalyzed significant private investment in clean energy both domestically and internationally. Karen Fang, Managing Director and Global Head of Sustainable Finance at Bank of America, noted the IRA’s role in sparking what she called a “manufacturing renaissance” within the U.S., with renewables like solar energy storage becoming one of the most cost-effective energy sources. Both BP and ExxonMobil, traditionally seen as fossil fuel giants, have publicly recognized the economic opportunities in clean energy, suggesting that their investments are not only about compliance but are also driven by the profitability and long-term stability that renewable energy offers — this has meant that companies plan to maintain their climate investments regardless of potential shifts in U.S. or global politics. Ali Zaidi, White House National Climate Advisor, underscored this resilience, noting that the momentum from the IRA and other climate commitments is too entrenched to be reversed by changes in administration.

The collaboration between governments, MDBs, and private investors continues to be identified as crucial to mobilizing climate finance at scale. Ajay Banga, President of the World Bank, elaborated on this approach, emphasizing that MDBs are positioned to act as “first risk-takers” in sustainable finance initiatives. Through platforms like the soon-to-be-launched Frontiers Opportunity Fund, the World Bank is setting up guarantee mechanisms to absorb early-stage investment risks, making projects in renewable energy and infrastructure more appealing to private capital. By leveraging public and philanthropic funds in this way, MDBs aim to de-risk high-impact projects in middle-income countries, offering private investors a clear pathway to sustainable returns.

This collaborative model resonates across private sector perspectives as well. Rich Lesser, Global CEO of the Boston Consulting Group, highlighted that consistency in public-private collaboration is key to scaling these efforts. He pointed out that a stable regulatory landscape and clear policy signals allow businesses to confidently commit to long-term, high-impact projects. Similarly, Andrew Forrest, Executive Chairman of Fortescue Metals Group, noted that Fortescue’s decarbonization strategy had proven financially viable without relying on offsets or carbon capture, underscoring how profitable low-carbon ventures can become within the right partnership frameworks.

By facilitating these collaborations, week one of COP29 has showcased how public-private partnerships serve as more than just financial support. They are a means to harness the expertise, resources, and influence of private entities, turning climate finance into a scalable, profitable venture that aligns with global climate goals.

Carbon Markets as a Pathway for Private Sector Involvement

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement which I track closely — carbon markets — emerged as a critical area for engaging private finance in climate solutions. The first day of the conference marked a breakthrough with the operationalization of Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, setting the stage for a globally regulated carbon market. This development has sparked significant interest among private sector participants, who view carbon markets as a key entry point for scaling their climate impact while accessing profitable opportunities in emissions reduction.

Carbon markets allow companies to invest in emissions reduction projects and trade carbon credits, creating a financial incentive for lowering greenhouse gas emissions. Simon Fellermeyer, Article 6 negotiator for Switzerland, emphasized during a panel that the successful implementation of Article 6.4 allows countries and companies to engage in international carbon markets with greater confidence. With established standards and removal guidance, this mechanism provides transparency and legitimacy to carbon credit transactions — factors that are crucial for private investors seeking stable returns.

For many companies, carbon markets represent an opportunity to align financial goals with sustainability commitments. Rachel Mountain, speaking at an event titled, Connecting the Dots between Policymakers in the Global South and the International Private Sector, noted that policy and regulatory clarity are essential for attracting large-scale private investment, as it enables companies to project long-term financial returns without fearing abrupt policy shifts. However, she also emphasized that fragmented regulations across regions could deter investors, stressing the need for a harmonized approach to carbon markets.

Beyond the corporate level, carbon markets offer developing countries a pathway to access private finance. Through revenue generated by carbon credits, countries can fund sustainable projects that might otherwise remain financially unviable. Tajiel Urioh from South Pole explained at the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) Pavilion how carbon credits provide critical financial support for locally tailored projects in low- and middle-income countries. He highlighted the importance of setting up robust national registries to coordinate with international regimes, ensuring that carbon credit revenue flows effectively and sustainably to support these communities.

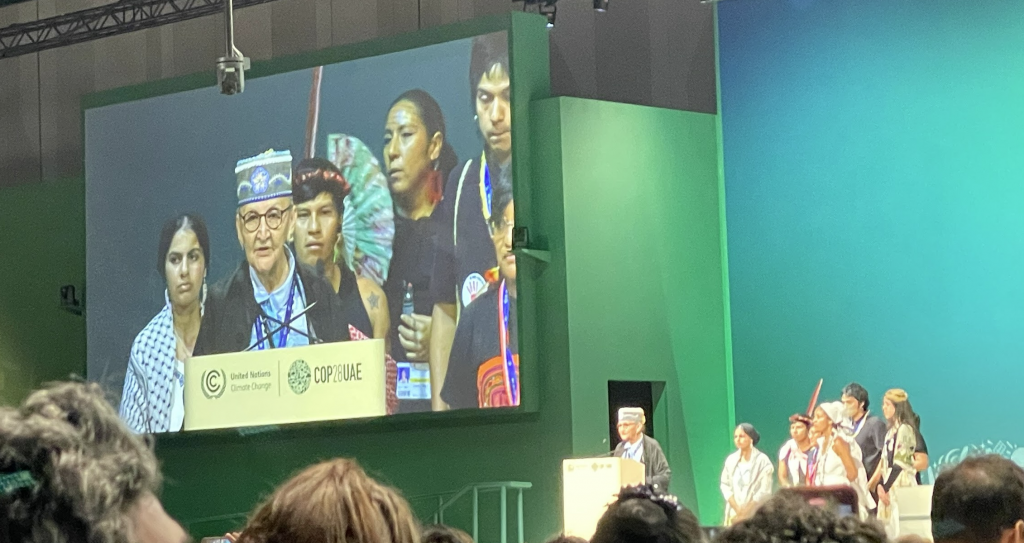

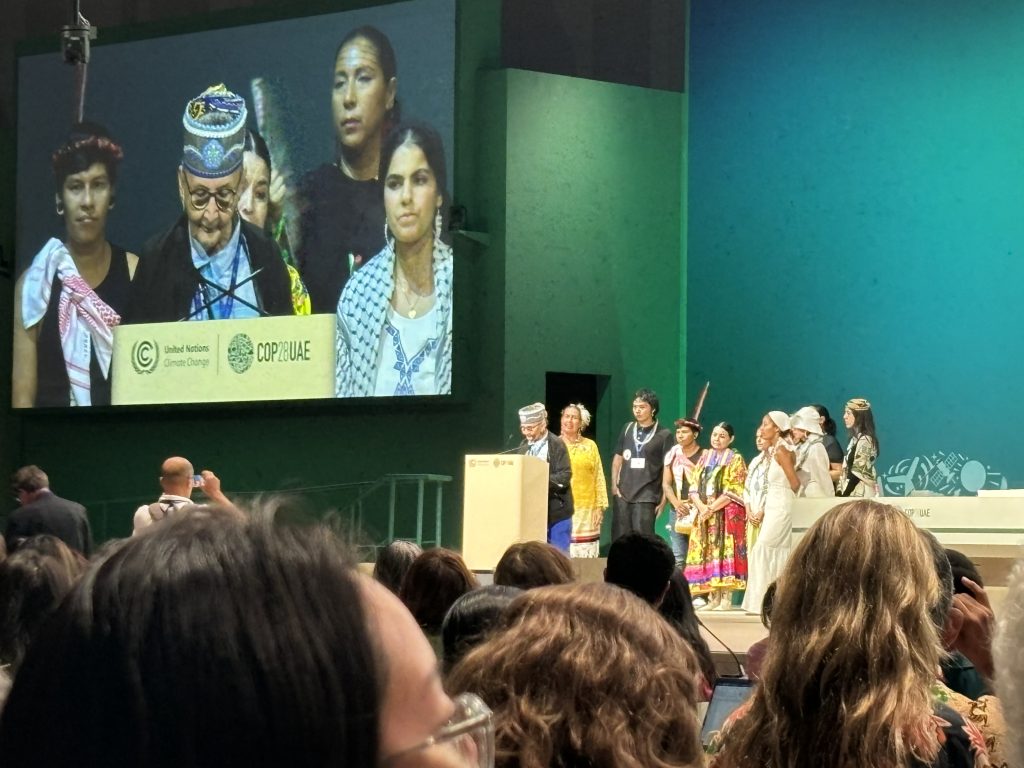

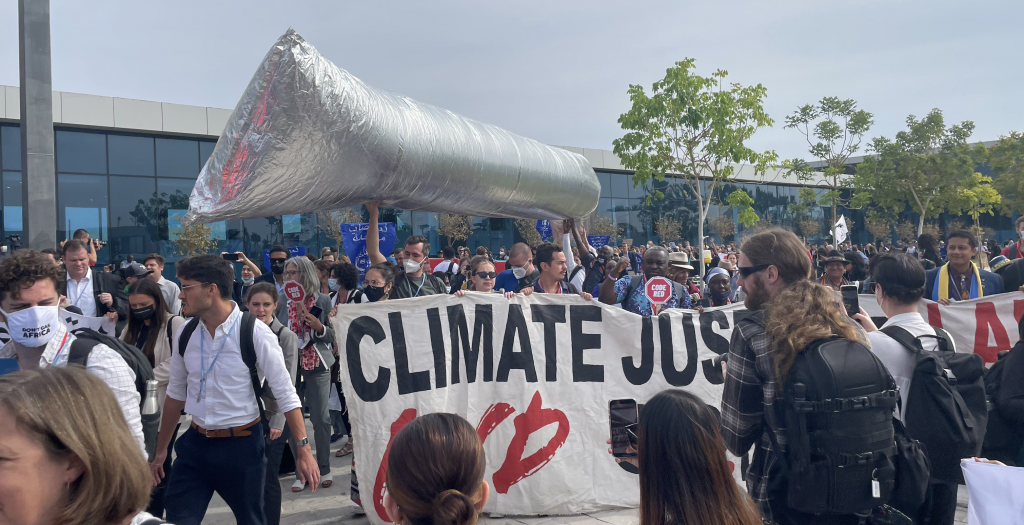

Despite the optimism, negotiations around the specifics of carbon market regulations are ongoing. Indigenous communities and climate justice advocates have expressed concerns about carbon markets, fearing they may lead to exploitation of land and resources without adequate protections for local populations. Many argue that, without strict safeguards, carbon markets could enable companies to offset emissions without making meaningful reductions, thus allowing “business-as-usual” emissions in wealthier countries. These voices are pushing for continued dialogue and accountability measures within carbon market frameworks to ensure they uphold equity and respect for Indigenous lands and livelihoods — it will be key to see how Article 6.2 and 6.4 negotiations end by week two.

The Path Forward: Mobilizing Trillions for Effective Climate Action

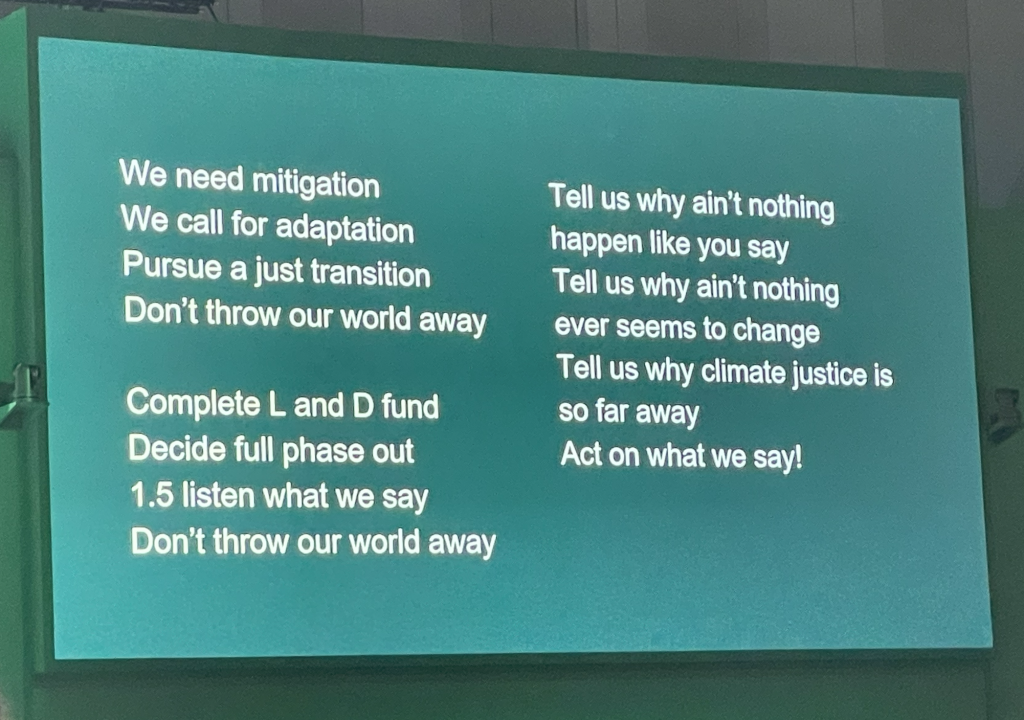

COP29’s discussions have underscored the vast scale of resources required to meet the NCQG and address the global climate finance gap. With projected funding needs estimated in the trillions, this COP has seen strong calls for wealthier, developed nations to increase their financial commitments. Many countries from the Global South, backed by climate justice advocates and protest groups at COP29, have stressed that high-emitting nations — particularly G20 members — should contribute a larger share, given their historic and ongoing emissions. The principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” remains central, asserting that while all nations have a role, those with greater resources and historical emissions bear a heightened obligation to lead in funding climate solutions.

To meet these ambitious goals, private sector investment is seen as critical. Nadia Calviño, President of the European Investment Bank, speaking on green bonds and debt-for-climate swaps, emphasized that innovative financing methods are vital to meaningfully involve private investors. Similarly, a high-level panel held by the World Economic Forum discussed the importance of streamlined permitting, consistent carbon pricing, and risk mitigation strategies to create an investment-friendly landscape, particularly in infrastructure and energy sectors.

As I look ahead to week two, I will be closely following the continued negotiations surrounding the NCQG, which will ultimately determine the scale and structure of global climate finance commitments. The outcome of COP29 will be crucial in shaping how effectively the world mobilizes to fund a sustainable future, with the balance of public and private finance likely to serve as a determining factor.