The first COP-24 delegation from Swarthmore has arrived in Poland! We are heading to the conference site this morning to get our badges so we are ready to hit the ground running tomorrow when the conference starts. Stay tuned for updates to hear what we are finding interesting during the week!

The first COP-24 delegation from Swarthmore has arrived in Poland! We are heading to the conference site this morning to get our badges so we are ready to hit the ground running tomorrow when the conference starts. Stay tuned for updates to hear what we are finding interesting during the week!

On our way to COP 24!

Our first delegation departs for Katowice, Poland, tomorrow, November 30th. Chemistry and Environmental Studies Professor Christopher Graves is leading a delegation of four students, all seniors: Amos Frye (Environmental Studies honors major), Shana Herman (Environmental Policy and Conservation Biology), Marianne Lotter-Jones (Biology major, Environmental Studies minor), and Brittni Teresi (Psychology and Environmental Studies double major). The team will arrive in Katowice on Saturday and attend the opening of the conference on Monday. We hope you’ll follow along with their adventures and post comments and questions to help them share the COP experience with you!

COP23 Day 4 – Climate Justice Day

After an amazing day yesterday hearing some great speeches and listening to the high-level segment, I decided to stop listening to the dignitaries deliver their addresses and go to more events. We tried to attend the negotiations, but we couldn’t get in since they went closed door. From looking at the published schedule it does seem like the APA negotiations proceeded because the APA plenary is back on the schedule. A lot of talk this week has centered around the divide between the global North and South, which is primarily responsible for shutting down the APA plenary yesterday. We’ll see if this divide sneaks into the closing plenary of COP tomorrow.

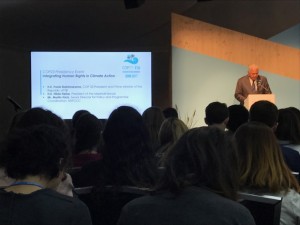

Since we couldn’t get in the room to hear the wheeling and dealing, I attended some side events. The one that stood out most prominently for me was a Presidency Event Integrating Human Rights in Climate Action, a fitting topic given that today was Climate Justice Day! It was presided over by the United Nations Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights (Kate Gilmore) and was opened by the COP23 President and Prime Minister of Fiji. He gave an excellent speech where the overarching message was that human rights are universal and our climate policies must protect the weak from the strong and give hope to those who are most vulnerable. The president of the Marshal Islands also gave opening remarks where she called for an end of the blame game, mentioning that all nations must be part of the solution and all actors have the responsibility to do what they can to help those in the most vulnerable places.

The panel discussion was excellent! The big take-a-ways were the need to engage everyone in climate action and to acknowledge the special circumstances, challenges, and opportunities that different groups bring to the table. One quote from a panelist: “If you aren’t at the table you are likely on the menu. Everyone needs to have a seat at the table.” Throughout this conference a lot of discussion has focused around gender inclusion as well as in engaging the indigenous peoples. Both groups had major wins at this COP, with the establishment of a Gender Action Plan and a Local Communities & Indigenous Peoples Platform. For decades the indigenous peoples have been trying to be engaged in the development of climate action, and there is a lot of positive energy here around the fact they’ve finally gotten an official voice. Hindau Oumarau Ibrahim, who has been a major presence at this COP, was a panelist during this session and once again gave a passionate speech about engaging the indigenous peoples to help develop ideas and install paths that will met their priorities. I have really enjoyed hearing her speak throughout the week. The session ended with a closing remarks from Mary Robinson, the president of the Mary Robinson Foundation – Climate Justice, where she urged us to feel good about the progress we’ve made and to use that energy to develop effective climate action strategies. All in all, it was an excellent session!

Week 2, Day 3 – Negotiation + Emmanuel Macron

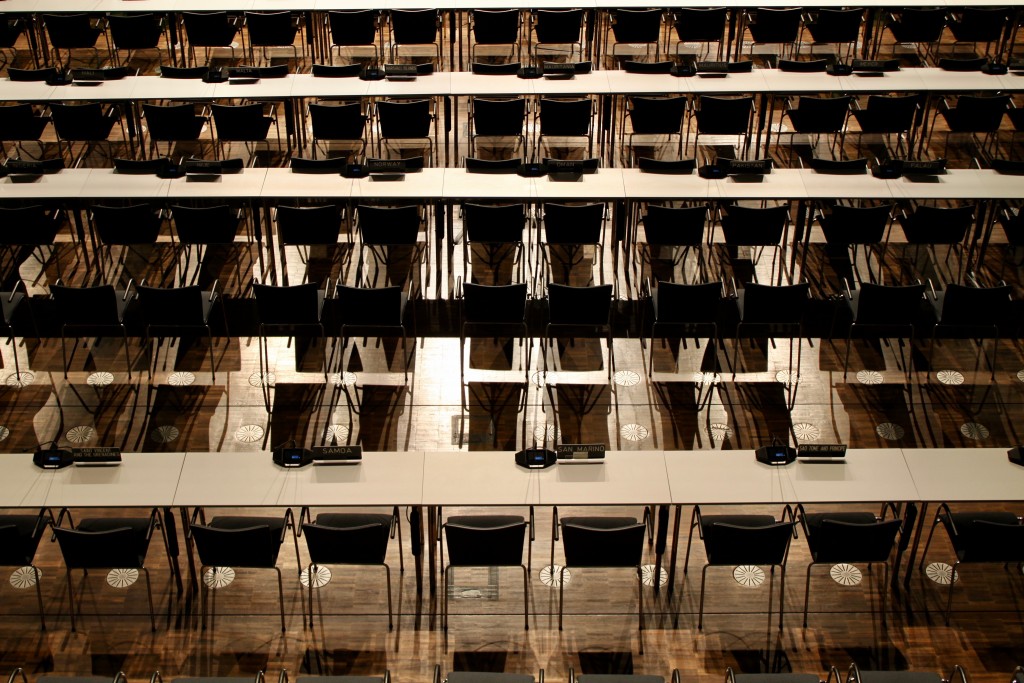

Guten Nacht from Bonn! On Wednesday, we got to see a lot of negotiations going on in the Bula Zone. As you (may) already know, the COP is split up in to two seperate zones which are in different buildings, the Bula and Bonn zone. The Bonn Zone is more accessible (as in, more people are allowed in) and is where most side events take place, which are the kind of events you would expect from a traditional conference where speakers present about all kinds of topics from gender/climate issues to indigenous rights and climate change to the science behind our climate. This is also where the country ‘pavillions’ are (pictured below).

The other zone, the Bula Zone, is where the actual negotiations between parties take place. This zone is connected to the Bonn World Conference Center, and fewer people are allowed access. Today, we spent our whole day in this zone taking in negotiations. Today was an exciting day because it marked the end of formal negotiating and a launch in to more of a fine-tuning process on the final agreement. There are several working aspects of the agreement that will produce documentation (see more info here: http://unfccc.int/meetings/bonn_nov_2017/in-session/items/10498.php), but the one I have been following the most closely is Ad Hoc Working Group on the Paris Agreement, or APA.

The APA is split up in to different agenda items. I got to see a working session on agenda item four yesterday, and saw two of the closing plenary sessions today. In both, South Africa played a prominent role in blocking up negotiating. It appears that South Africa has several issues with the current APA informal notes (see above link) specifically in agenda item 8a. This led to them requesting an adjournment on a technicality in the closing session, which led to the session being temporarily suspended not once, but twice. They plan to meet later in the week even as the fine tuning negotiating begins.

In the high-level session tonight, Angela Merkel (Chancellor of Germany) and Emmanuel Macron (President of France) both spoke about the necessity of climate action. Chris got a ticket into the room, while Shiv and I watched on a screen in an overflow conference area. Macron went so far as to say that the rest of the world is moving on without the US and France has no qualms about stepping up to fill the gap. He also said that he is considering a ‘border tax’ against the US to help fund the Green Climate Fund, which is a fund that is pooled by richer nations to give grants to developing countries to help them get renewable energies off the ground (read more here: http://www.greenclimate.fund/who-we-are/about-the-fund).

After a long day at the conference, Shiv, Chris and I had dinner at a nice German restaurant near our hotel before heading back. Check back tomorrow for another update!

Week 2, Day 2 – Happy Gender Day!

Governor Kate Brown of Oregon, a powerful woman, speaking about the climate policies she has successfully implemented in her state.

Today was the COP 23 Gender Day, a day meant to “highlight how gender-responsive climate policy and action can provide economic benefits to communities and create opportunities for raising ambition under national climate plans, while transforming lives, particularly of women and girls”. Before getting into my observations from Gender Day at COP23, I’ll go into a little background information on gendered climate issues.

The 2013 COP conference was the first year that the disproportionate affect of environmental degradation on women was recognized on a large-scale. The initial title was “Women’s Day” and it intended to highlight women’s involvement in environmental issues and provide women with a larger platform to voice their issues and empower themselves. The title “Women’s Day” was changed to “Gender Day” because focusing on women instead of gendered power structures depicted women as victims, furthering their subjugation in the matter.

I’m sometimes met with confusion or skepticism when I say women feel the impacts of climate change more than men. However, women and children are fourteen times more likely to die in ecological disasters than men. Greta Gaard provides interesting case studies in her article “Ecofeminism and Climate Change” (2015),

“...women and children are 14 times more likely to die in ecological disasters than men (Aguilar, 2007; Aguilar, Araujo, & Quesada-Aguilar, 2007). For example, in the 1991 cyclone and flood in Bangladesh, 90% of the victims were women. The causes are multiple: warning information was not sent to women, who were largely confined in their homes; women are not trained swimmers; women's caregiving responsibilities meant that women trying to escape the floods were often holding infants and towing elder family members, while husbands escaped alone; moreover, the increased risk of sexual assaults outside the home made women wait longer to leave, hoping that male relatives would return for them. Similarly in the 2004 Tsunami in Aceh, Sumatra, more than 75% of those who died were women. In May 2008, after Cyclone Nargis came ashore in the Ayeyarwady Division of Myanmar, women and girls were 61% of the 130, 000 people dead or missing in the aftermath.”

Again, critics might say something along the lines of “Well this is anecdotal and not relevant to developed nations!” Well that’s the point. The adverse affects of climate change are not felt by the people responsible for it, and further are especially detrimental to marginalized communities.

“Unbearable” art installment on the walk between the conference zones. The bear is being impaled by an oil pipeline that is curved to match the growth of the carbon in the atmosphere (ppm).

The events at COP23 for Gender Day focused on having women being the focal points of their own climate solutions. I attended a panel called The Economic Case for Gender-responsive Climate Action, where the speakers from different cultural and economic backgrounds spoke to the importance of governments to seek or promote, and investors (both private and public) to fund climate policy and action that considers the needs, perspectives and ideas of not only men but mostly women. The panelists spoke to the importance of centering gender-responsive climate action around women in communities they are already passionate about in order to further community well-being actions. The VP of Global Themes from the World Bank, Hart Schafer, made an interesting point that it is economically irresponsible for countries to not consider women as assets in development, because they are 50% of their market. He explained that the World Bank seeks out local women to engage in grassroots movements to alleviate damage from natural disasters, and statistically the efficiency of the aid is significantly worse when they failed to address gender disproportionality as an issue.

Another aspect of Gender Day and the COP23 conference in general that is worthy of analysis was the presence of Indigenous peoples in a more mainstream way. As we know the conference is being hosted by Fiji, but is physically in Bonn because Fiji lacks the resources and climate security to commit to such a large event. The presence of indigenous peoples on the panels and as leaders in this conference shifts the focus away from a science and development centric approach, and reminds people on an international scale that marginalized, “other” communities deserve a better voice in these forums.

As much as I appreciate Gender Day and it’s existence, it still feels like an afterthought or a strategy for appeasement. If UNFCCC can recognize gender-responsive climate action as a priority enough to create a day, then these actions should become a given part of NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions). In 2016, WEDO (Women’s Environment and Development Organization) analyzed every country’s total, and came out with a report,

“In total, 64 of the 190 INDCs analysed include a reference to women or gender. Of these, several only mention gender in the context of the country’s broader sustainable development strategy and not specifically in relation to climate change policies (e.g. India).”

NGOs are doing incredible things to promote gender-responsive climate action, mostly at the grassroots level. I hope to see increased support on national levels and more talk of gender in negotiations in future COPs.

Panel for WEDO awards on gender-responsive climate action grassroots organizations.

A final critique I have would be the lack of inclusivity and intersectionality in relation to environmental justice issues at the conference in general. These issues are discussed briefly with gender normative language and often frame women as needing to be “brought” to the forefront of these movements. We need to stop seeing women and other marginalized peoples as victims, and begin to deconstruct the existing power structures and “norms” we’ve accepted for so long. This requires an uncomfortable process of self-critique and relinquishing control, but it is something we can achieve with mindfulness and humility. This being said, I am excited to see the progress the Environmental Justice movement has made on this international stage, and have faith that it will continue to develop and manifest into policy in future COPs. As the Deputy Prime Minister of Samoa Fiame Naomi Mata’afa stated so well in the economics panel, “We know what we want, we’ve known for a long time. It’s time to just do it already.”

*Edit: 11/15/17 In the closing plenary of the SBI (Subsidiary Body for Implementation) it was announced that a Gender Action Plan was adopted in the UNFCCC. At the SBSTA (Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice) closing plenary an agenda idem with an Indigenous People’s Platform. It was exciting to see more substantial documents of the needs for better representation.

Week 2, Day 1 – Engage, Engage, Engage!

Today was our first day of the COP-23 meeting. I started the day by attending the RINGO debriefing meeting where we got the status on several of the negotiations pertaining to implementation of the Paris Agreement. It was a good way to start and gave a big picture overview of the progress made thus far. A general takeaway was that things are moving slowly, but the chair of the session assured us that this was normal.

For the rest of the day I moved to the Bonn zone and attended several side events. The theme of the talks/sessions from my day focused on the need and importance of engaging local communities and governments in the process of climate adaption and mitigation. I first attended the High-Level Opening of Global Climate Action where I saw Gov. Jerry Brown (CA) talk for the first (not the last) time. He spoke very passionately about the need for states to pick-up the slack where the federal US government has failed. He was followed by a panel of an interesting group of dignitaries from around the globe and from different sectors. The representative from the Indigenous People’s really stood out for me as she stressed the need to engage local people in the mitigation and adaption process and to enable them with an action plan. In this vein I also I went to a side event focused on regional collaboration centers (RCCs) that pair local government organizations with bigger entities to help establish carbon pricing (and other) initiatives. The panel was interesting as several people discussed their specific projects or hopeful projects, although the “high end” portion consisted of dignitaries patting themselves on the back, which I found dull.

I spent a good chunk of the middle of my day exploring the venue and the pavilion. What a great group of diverse individuals! I spent some time at a science hour at the German pavilion and gathered a lot of pamphlets and information that I think will help me in my courses next semester. I also discovered that the Russian pavilion is going to have an entire session Wednesday devoted to progress toward a more carbon neutral refining of aluminum (my favorite element) so I am pumped!

I wrapped the day up by attending a session on Sub-National Strategies in North American for Meeting the Paris Commitments. It was opened with two governors (Kate Brown (OR) and Jay Insee (WA)) discussing their state initiatives and commitments to battle climate change. It was the first time for me at this meeting where a person directly spoke about Trump. The opening was by an excellent panel with Canadian and Mexican dignitaries as well as Gov. Brown. I was really inspired about all the state and provincial level work being done in the three countries. I was also filled with hope when the Minister of the Environment from Ontario reminded the USA people that Canada once had an environmentally unfriendly federal government (the Harper administration) and in those time the provinces made huge initiatives. It was a ray of hope that the state-lead coalitions will be able to do great things under the Trump administration. I look forward to learning more about these initiatives during the We Are Still In events over the next few days.

Week 2, Day 0: Willkomen! Bula! Welcome!

Hi everyone! We hope you enjoyed keeping up with Aaron Metheny and Kyle Richmond-Crosset, and Professor Jennifer Peck last week, this week we (Shivani Chinnappan, Samantha Goins, and Professor Chris Graves) hope to bring you interesting new insight on the inner happenings of COP23.

In the wrong seats on the train, but it worked out.

Between leaving Philly and arriving in Bonn we covered several modes of transportation; after a 71/2 hours flight, a 45 minute train ride, and a winding drive up steep hills we arrived at our quaint hotel nestled in the hillside of a neighboring town called Königswinter.

The view from our hotel room (left) and some signage on the way to the conference center (right).

We visited the conference center to get our badges, but were unable to access the center until tomorrow when our badges are officially active. We decided to utilize the time and beat the jet-lag by exploring a bit. There was a Christmas Market nearby, a European classic, where we enjoyed some cocoa and ended up mingling with a representative from the U.S. that works for a NGO that works to build jurisdictional programs to protect forests while promoting rural livelihood.

A crepe stall at the Christmas Market.

It was exciting to interact with other groups from the U.S. and see the continued effort even through withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. After the market detour, we walked through downtown Bonn and found a place to eat some delicious traditional German cuisine.

Public Transportation: Harder Than it Looks

Now, after 24 hours of sleepless travel, we are signing off. Check back tomorrow for updates about our first day at the conference!

COP 23, Day 5/6: Bonn Voyage!

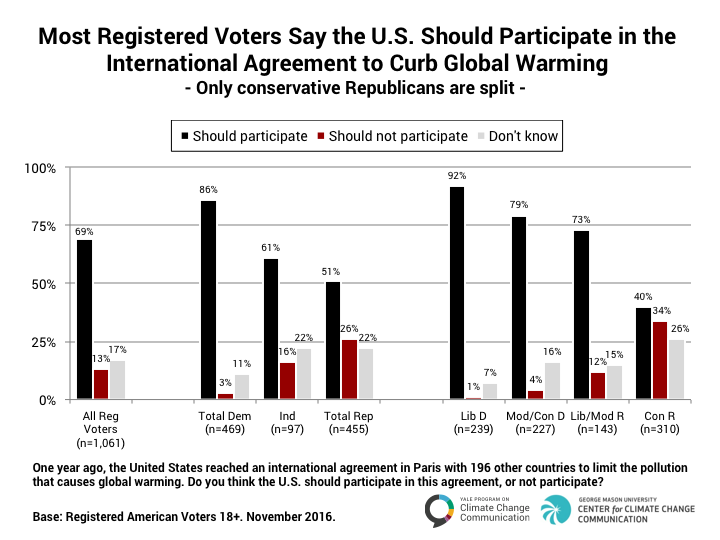

Apologies everyone, this blog post is a little late due to the hassle of packing and traveling back to the States (we made it back safely!). Reflecting back on the last few days at the conference and on the week as a whole, I can’t help but feel grateful for this tremendous opportunity to witness and engage in international climate change policy negotiations. On Thursday, I attended the first events of the We Are Still In Campaign, which generally featured informative panel discussions concerning the economic solutions to climate change. On Friday, we were able to listen to a sobering and inspirational talk given by Al Gore on the climate crisis. I also was able to go to a event on Yale Program on Climate Change Communication’s latest survey on US public opinion on climate change juxtaposed with a similar survey commissioned over the summer in China. While most Chinese believe in anthropogenic climate change, Americans are generally skeptical of the connection to man-made causes. The panelists suggested that the failure of domestic action on climate change is because of the absence of an organized and vocal grassroots movement that would increase salience this issue in the public mind and pressure the federal government to implement policy change. It will be interesting to see if Sam, Shiv and Professor Graves see more of this bottom up mobilization from US businesses, state/local governments and environmental justice organizations in the second week of negotiations. Overall, attending the first week of COP 23 was an unforgettable experience!

Look for more pictures here!

COP 23, Day 4: The Two US Delegations

Today marked the kickoff of events in the US Climate Action Center, the non-federal US pavilion hosted by We Are Still In. I attended these events as well as a session of the informal working group on item 7 of the Ad-Hoc Working Group on the Paris Agreement (APA) agenda.

The US delegation is led by US undersecretary of state for political affairs Thomas Shannon, a career diplomat and Obama-era appointee. The negotiators seem to be experienced COP participants, some with long histories with the climate negotiations. From reports from other RINGO constituents and our own observations in the meetings, the US delegation has been relatively subdued but not absent from the negotiations. US negotiators seem engaged in issues of process and substance in the informal sessions for the APA and the Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage.

The “unofficial” US delegation has been anything but subdued at this meeting, holding events in a network of inflatable domes just outside the main negotiations. The Climate Action Center is huge and very polished. (The cost of the regular pavilions is 380 euros per square meter +19% VAT).

This is the hub for the delegation of US non-federal leaders, including mayors, governors, corporate executives, clergy, and university presidents who are attending the COP. William Shatner was not able to attend in person but sent his well-wishes via video.

This an interesting group: not party to the official negotiations, but it is positioning itself as a group with the capacity to meet US mitigation and financial commitments under the agreement. People at the conference seemed a little puzzled about the division, and some members of the group itself seemed likewise unsure of their specific role at the conference.

On the first day of the conference I attended a panel hosted by the Climate Action Network, an environmental NGO with a large presence at the conference. Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientists, a Washington-based non-profit working on environmental issues, spoke about the US role at the negotiations, emphasizing that subnational groups were trying to both cut emissions and mobilize climate financing to help the US meet its commitments under the Paris Agreement. A question from the audience about who other parties should be negotiating with, Meyer emphasized that negotiations about transparency, finance, and other official matters must go through the federal delegation, but he urged participants to think of the current administration as an “aberration” rather than a long-term trend in US climate policy. He highlighted the role of the US subnational-delegation as being closer to public opinion than the executive branch of the government. This point came up in the afternoon today when Mayors and State Representatives in the non-state delegation talked about responding to the demands of their constituents.

The event started with remarks by James Brainard, the Republican Mayor of Carmel Indiana. He made the case that there is more support for climate action in the Republican party than is reflected in the executive branch of the government and talked about the nonpartisan history of environmental protection in the United States. (He later talked about the capacity for state and local-level change as a benefit of not ceding too much control to the federal government.)

Mayor Brainard was then joined by a group that spoke about achieving climate goals from the perspective of faith groups, corporations, universities, cities and states. A member of the audience asked the panelist how they hoped to engage with the other countries at the conference, and their responses were understandably vague, since there’s no official channel for them to do so.

The second event focused on market mechanisms to achieve climate progress. Speakers from business and industry talked about offsets, carbon pricing, and investing in renewables. California Assemblymember Cristina Garcia spoke about using cap and trade revenues and real-time local environmental monitoring as a tool to achieve environmental justice in disadvantaged communities.

The main priority of the non-federal US group at this point is to make visible US sub-national support for the Paris Agreement. The US Climate Action Center events today focused on broad strokes of different approaches to achieving the Paris Agreement goals, and events later in the week are supposed to go into more specifics. Perhaps future COPs will have a larger role for the US sub-nationals.

Day 3: Fossil of the Day, and other stories of Non-Party Stakeholders

The third day of COP23 was packed to the brim with dozens of informal negotiations, party roundtables, and side events hosted by some of the many non-party stakeholders attending the conference. This COP has about 19,000 attendees, including more than 11,300 party delegates and about 6,000 non-party stakeholders, and there are complicated rules about which events are open to which participants.

According to someone I talked to who had been to many previous COPs, almost all negotiations (except for the most informal discussions) used to be open to anyone with access to the conference. As the size of the conference has grown, the negotiations have become more intense, and information is more quickly distributed, the parties have become more hesitant to allow non-party stakeholder observers into negotiations. At the same time, many of these stakeholders have cultivated personal relationships with career diplomats who attend many consecutive COPs, and so while more meetings are now technically closed, exceptions are often made on the request of party delegates.

Countering the trend of increasingly limited access and ability to influence negotiations directly, the Fiji Presidency has made it a point to engage non-party stakeholders in productive dialogue. The highlight of this approach was the Open Dialogue, a discussion that took place this morning with several dozen party delegates and representatives from the nine non-party constituencies. Two of the most relevant of these constituencies are YOUNGOs (YOUth NGOs) and RINGOs (Research and Independent NGOs); Aaron, Jennifer and I have been attending their daily meetings. During the Open Dialogue, delegates from both parties and non-parties agreed that connections between civil society and government, both domestically and during climate negotiations, were critical to enhancing the ambitions of the Parish Agreement. That being said, despite being labeled a dialogue, the meeting could have been more aptly described as Stakeholders Reading From Written Statements, and little to no substantive outcomes were reached. Clearly, more dialogues are needed.

In addition to the Open Dialogue, NGO constituencies get a brief amount of time to speak in what is called an intervention at specific negotiating meetings called open plenaries. One of the highlights of my week so far was frantically editing an intervention about climate finance for YOUNGO in the back of an open plenary meeting, minutes before our representative read it to the parties and observers at the meeting.

Beyond formal interactions between parties and non-party stakeholders, many climate action organizations are engaged in a massive effort to lobby delegates, shame uncooperative parties, and shape the topics of discussion. With the help of the Swarthmore hub of the Sunrise movement (shout-out to Aru), I have recently become a member of the Climate Action Network, a network of climate action organizations that work together to influence the negotiations and push a progressive climate agenda. As a result, I have seen some of the incredible behind-the-scenes work that goes into maintaining a coherent and consistent climate action campaign. For example, the Climate Action Network organizes a daily event at 6pm titled “Fossil of the Day,” in which a theatrical man dressed in a skeleton sarcastically presents an award to the party that has acted poorly or stalled negotiations. While very silly, shaming countries into behaving more constructively is important, especially when one party can hold up progress on any agenda item.

In the end, the Paris Agreement can be signed only by parties, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are determined by national governments, and the COP by definition designates the Conference to be “of Parties.” But even in the short time we have been here, it is clear that non-party stakeholders have a serious role to play in framing the conversation and applying pressure with the goal of concrete and ambitious climate action.