By: Prof. James Padilioni, Jr.

“Africa is NOT the Global South! Africa is the center of the world!” So exclaimed an attendee at the Yasunize Movement demonstration I observed at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan. Yasuní is a national park located in the Ecuadorean Amazon which UNESCO has declared a world biosphere reserve in recognition that Yasuní features the highest biodiversity of any singular ecosystem on our planet. In August 2023, the Ecuadorian people voted to halt all future oil drilling within the borders of Yasuní National Park, representing a threshold moment for a true transition away from a fossil fuel economy that does not involve the abstract mathematical manipulation of instruments via a carbon market. As such, “to Yasunize” has emerged as a new rallying cry for an environmental geopolitics that questions economic growth and dependence on oil as the only markers of development. Thus, it was evocative for this demonstration at COP29 to signal not only a new paradigm for just transition, but to reorient our global compass and our directional imagination of civilization away from the North-South stratification that constantly places the Global South in a position of extraction and need relative the political economic imperialism of the Global North, specifically North Atlantic modernity in its Euro-American latitudinal influence. In this new cartography of climate action, neither Africa nor Ecuador are the “Global South” relative to an overdeveloped Global North; these locations, and the stalwart climate activists that call them home, are the center of the world, leading us into whatever semblance of a sustainable future we may yet bequeath posterity — if we are so lucky.

I open this year’s reflections on COP29 for the Swarthmore @ COP blog with this anecdote because it signals the indomitable energy of resolution that many negotiators and delegates from the so-called Global South have taken upon themselves, especially in light of the impending second administration of Donald Trump. Our week 1 delegation left Swarthmore just 4 days after Election Day, traveling to Baku, Azerbaijan in a swirl of affect that threatened to derail the intentions of COP29 before it even began. Here, it may be useful to refresh our memory of “the long national nightmare” that was Trump 1.0: less than 18 months after the historic adoption of the Paris Agreement of 2015, President Trump pulled the United States from complying with our Nationally Determined Contributions both in our attempts to scale-down our fossil fuel dependence as well as our pledges to provide financing and cash payments to those developing nations of the Global South who need variously to adapt, mitigate, and/or respond to the losses and damages of climate change and extreme weather events. During the first Trump administration, the common sense sentiment began to emerge that it was necessary for the US, as the world’s largest and most-developed economy, to “reclaim the global lead” on climate action, with the lack of such leadership representing a stumbling block to the climate governance regime enacted by the UNFCCC. (The folks who honestly spout such rhetoric are usually blind to the American exceptionalism of their argument, and the patronizing, Marshall Plan-style way it addresses the globe, but I digress). The United States remained out of compliance with the Paris Agreement until President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, the largest investment in climate resiliency in US history. President Biden, thus, made a triumphal return to COP27 in Sharm El-Sheik, Egypt, where he gave a speech from the plenary hall to thunderous applause. Now, just 2 years later, and with only 12-15% of the IRA’s funding appropriations actually paid out, the United States is, once again, on the brink of puling out of the Paris Agreement, and perhaps from leaving the UNFCCC regime entirely.

(I am old enough to have been a perspicacious 7th grader who observed President Clinton sign the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, the first binding multinational agreement on climate emerging from the UNFCCC. I am also old enough to have been a 10th grader who remembers the newly-elected President George W. Bush refuse to cooperate with Kyoto, and I recall the 95-0 senate vote against its ratification. The UNFCCC has watched the United States, like a geopolitical pendulum, swing both ways many times before, flaunting the climactic reality and thumbing its nose at the world.)

Thus, one might speculate the mood at COP29 would be grim, pessimistic, forlorn even. But instead, the energy here is one of urgent confidence, as the rest of the 198 Parties to the Conference are resolved to fill the void left by the withdrawal of Trump’s America from the global world. Indeed, one might even detect a whiff of “good riddance” on the part of the Parties who remain, steadfast in their conviction that we are the last generation of humans who can effectively hold planetary warming to an average increase of 1.5 degrees celsius (perhaps 2.0 would be a more realistic, yet less ideal benchmark).

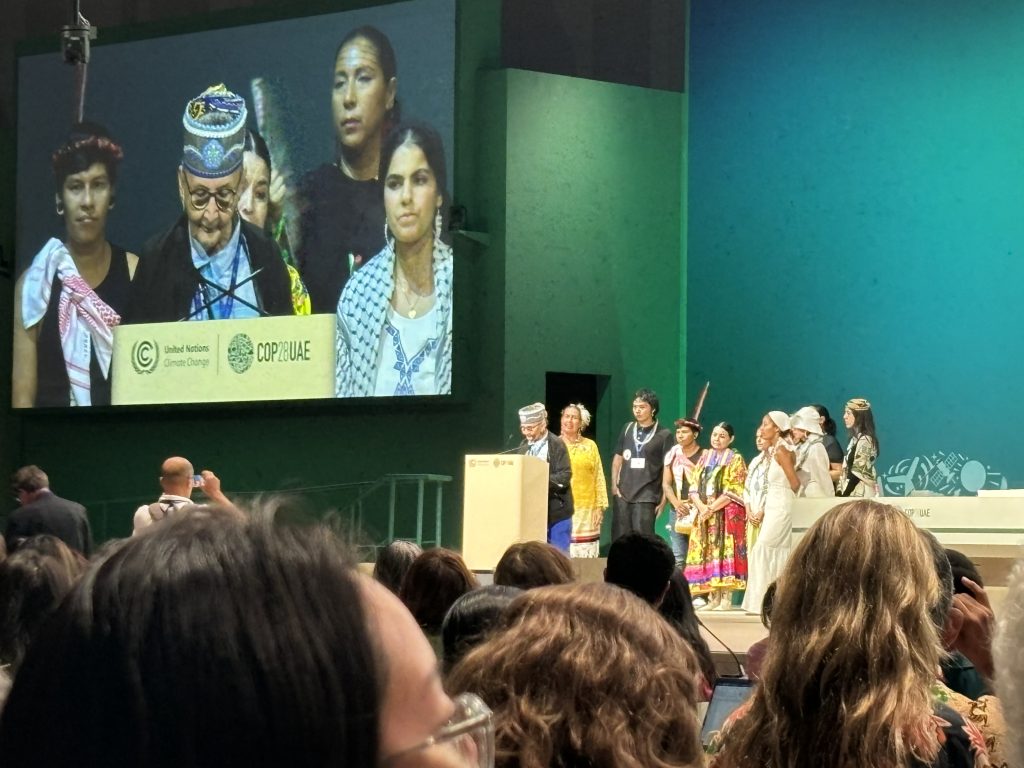

To this end, the delegates and observers — including Swarthmore’s week 1 students — have engaged the conference in eager pursuit of keeping the intended goals of COP29, namely, settling the business of the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG), a plan first agreed upon in 2015 to set a new goal building upon the floor of $100 B USD. Beginning in 2021, an ad hoc work program was established to facilitate technical discussions around the NCQG and to take stock of progress made in 2022 and 2023. The plan for this year is to tabulate these needs and set the NCQG — with or without the United States, this work must continue.

But what, exactly, is to become of the United States? I observed a press conference panel hosted by the Environmental and Energy Study Institute featuring Serena McIlwain, the Secretary of Environment for the state of Maryland, Wade Crowfoot from the California Natural Resources Agency, and Melissa Logan, mayor of Blytheville, AR, located along the banks of the mighty Mississippi River. These three American politicians and policymakers — two Black women and one indigenous man — instigated renewed hope as they confidently and boldly projected a plan of action at the state and local municipal levels to mobilize “boots on the ground” in support of maintaining America’s NDCs, despite the Trump Administration’s impending dereliction of duty. In particular, Mayor Logan passionately promoted the Mississippi River Cities and Town Initiative which includes a bipartisan collaboration between over 150 mayors whose towns and cities line the Mississippi River, one of the world’s most critical lifelines, a waterway whose transited goods supply 1/12 of the globe’s population with their necessary provisions. The work of sustainability will continue because it must!

Across the next two weeks, two groups of Swarthmore students will observe the proceedings of COP29, networking with likeminded advocates and documenting the progress of the NCQG. This blog will feature several of their reflections and form a digital guide for the broader Swarthmore community to follow. Additionally, our students will takeover the Swarthmore Instagram page, and we are planning a spring 2025 on-campus panel to help contextualize the stakes of COP29 for our local campus and borough community. Be sure to follow along!