As a student with an interest in the science of climate change, I was excited to have the opportunity to broaden my horizons and engage with the policy and activism aspects of climate change at COP22. My focus for the week was understanding the role that scientists play in creating and guiding climate change legislation, as well as their methods of effectively communicating their work and the seriousness of the situation.

I was luckily able to participate in Earth Information Day, which was designed to be a discussion of the up-to-date state of the climate and an opportunity to optimize engagements and connect information between the scientific community and party delegates. Held in one of the two giant plenaries on site, I looked forward to what the forthcoming discussion held.

Many of the talks given by the scientists focused on their new data sets and models of projected temperature increases. The main overarching theme was that more money and resources were needed for research and measurements to go from a global background level to a higher resolution regional scale, with the ability to pinpoint accurate levels of carbon emissions and temperature increases in specific areas.

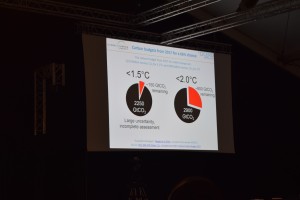

A delegate from Mali asked why the goal of keeping temperature increases below 1.5 °C was no longer possible. I was shocked to hear one of the scientists on the panel respond that the goal of 1.5 °C or below was still a possibility. Throughout the conference, the scientists pushed the message that we could limit temperature increases to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels. I was distraught to see this because the honest truth is that even if we completely stopped carbon emissions today, we would still surpass 1.5 °C and probably 2 °C. It was difficult for me to discern if the scientists legitimately believed this or if this was a message meant to maintain hope. While the numbers of 1.5 or 2 °C hold symbolic value, I think that they focus people on goals that are unrealistic and divert attention from pressing issues such as how vulnerable countries will adapt. Sure, these are numbers that can be advertised and sound really nice to everyone. But they assume that future technologies such as carbon sequestration will play a big role in limiting emissions to the atmosphere and that as part of the Paris Agreement opt-in system, countries will continue to enhance their emission limits.

Although more detailed data would certainly be helpful, I was frustrated that this was the main talking point. Doing more research is the easy part; as scientists, we can all continue to play our usual parts and produce more data. What is far more difficult, but more necessary, is to shift our focus towards advancing our science into social realms to ensure that our data are taken seriously and properly translated into public policy. If the data clearly show that climate change is occurring due to anthropogenic influences and that there are exponentially increasing temperatures, shouldn’t our priority be to make sure that climate change policy meets the requirements of what our data demand to avoid catastrophe? How do we clearly communicate important results such as the fact that the last time we were this warm 125,000 years ago, global sea levels rose 5 – 9 meters (Dutton and Lambeck, 2012)? We must transition away from remaining impartial and begin to engage with policy makers and the public, even if it will require time and for us to move out of our comfort zones.

Unfortunately, none of the speakers seemed to discuss techniques for communicating science and effectively making sure that policy reflected the increasingly dire outcomes for people and biodiversity around the world. As a result, at the end of the first discussion session I clicked a button to activate my microphone and asked the panel of scientists how well they thought policy makers incorporated their data. It wasn’t clear if they didn’t want to answer the question or didn’t take me seriously as a college kid, but they skirted around my question and responded that they believed governments took the issue of climate change very seriously.

At the end of the day, the bedrock of the UNFCCC process is fundamentally based on high-precision science. More research needs to be done to understand how climate change will affect diverse ecosystems around the world and how deleterious effects can be mitigated.

However, that is simply not enough.

As a scientist, I am used to being able to put in the time and effort to do experiments and accomplish my goals. However, I quickly realized at COP22 that the realm of climate change politics was a formidable foe and a completely different and uncomfortable game that involved compromises, a bit of propaganda, and extreme patience. But that does not mean that we can shrink away and wait for others to draft policy.

Rather, we must engage and fight to make sure that people understand the consequences of our data and that social policies of vast importance include responsible features that acknowledge and account for the current and future problems that science has shown we will all face.

As scientists, we must drop the fear of drawing attention to ourselves and speak up to the world even if our first attempts are incoherent or not well received. We must reject the alarmist label from those who do not believe our science or consciously choose to discredit it. In order to find solutions to a global problem, we must collaborate with each other, scientist to scientist, across other disciplines, with everyone; and reject the norm of individual achievement as the driver of scientific career progression. We must be politically active and support politicians that are in favor of increased funding for research. We must reach out and incorporate the public into our work to demystify science, increase transparency, and reduce the power dynamic between scientists and the public. These are all things that I believe that scientists must and can do.

Let’s hold off on “smiling for the planet” until we make sure that policy reflects what decades of data have been telling us.

– David

Dutton, A. and K. Lambeck. 2012. Ice volume and sea level during the last interglacial. Science 337(6093):216-219.

Footnote: If you are interested in learning more about how the science can become better incorporated into the humanities and social science, check out Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge by E.O. Wilson.