by Chris Stone ’23 (he/they)

Let me start off by following up on a few of the things I was looking for in my last blog post:

- Yes, I did find a handful of other peers from Myanmar.

- Yes, I did find a better understanding of why it matters that I attended this conference.

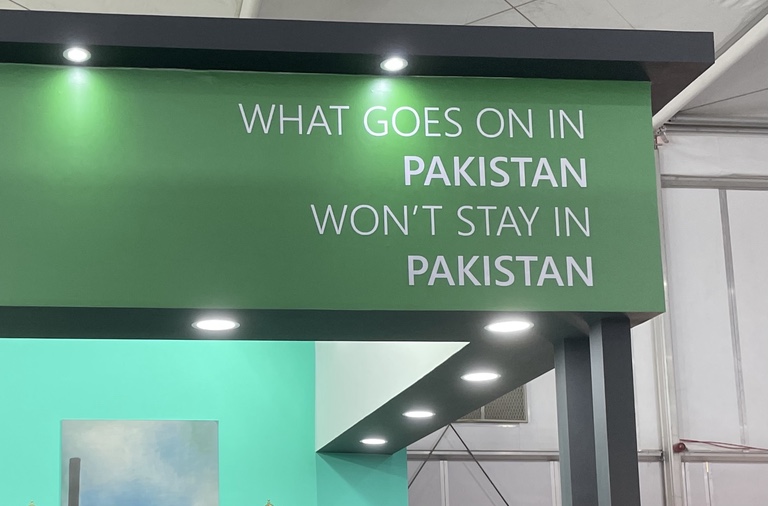

The two are closely tied. After panels, there’s often space made for the audience to pose questions to the panelists or contribute comments based on the topics raised. Through these opportunities, I spoke about issues concerning Myanmar and it’s people, both within the country and outside of it. It was a chance to bring to light that even if we aren’t being brought to the table, our voices should still be heard. I’m reminded of the slogan that across the Pakistan Pavilion.

The mentality by those in positions of power that the issues they’ve caused within the sacrifice zones, ones they benefit from, won’t have any negative repercussions disregards the ways we are inextricably linked. The climate catastrophes in the Global South and reconstructions of the Global South won’t stay there either. As to the campaign led by the Climate Action Network International (CAN-I) on Friday: The Flood Is Coming, and that means to everywhere.

Similar to the pavilions themselves, sharing my voice publicly at the conference drew others toward me. At first, those people included high schoolers to professionals interested in what I was sharing about heritage, (climate) refugees, and food systems. Until finally, after one event, I met several friends from Myanmar at once working on issues from indigenous advocacy to climate finance. I was overjoyed, even while we had to jump between English and Burmese to keep up the conversation, to meet others also conscious of how often topics around climate change are quick to brush over the needs of people in Myanmar. It gave me clarity that the direction I have been heading in hasn’t been for nothing after all.

It also became clear to me how my platform can be used to share information that those who remain in the country may not be able to speak up about without risking their livelihoods. This was a harder thing to face, both that as diaspora I had the power to address a particular leverage point at the seams of systems of oppression, and that it might mean all the longer that I am unable to go back.

I think back to how I felt when I first learned the term transgender. Joy: the past fourteen years of my life finally made sense. Fear: the rest of my life will be spent facing discrimination.

Joy: I have a whole community and history of trans folx to stand alongside.

It may be a long time till I return to Myanmar… but as I eat lunch alongside the Asian Pacific Islander Caucus, where uncles and aunties have brought back food they cooked back in the places they’re staying, I know that home is here too.

The networks that others had been connecting me to while I had been searching for others from Myanmar were not for nothing either. Through them, I found opportunities to participate in some of the demonstrations happening around the conference. In these messages, I learned that the venue had designated action zones and that these actions had received approval from the UNFCCC, though I’m not sure how many action zones there are, where they all are, or how many actions actually receive approval.

The majority of demonstrations I saw took place at “Action Zone 1”, right by the entrance, though I saw demonstrations at two other locations. Primarily led by BIPOC folx, they were for the purposes of demanding loss and damage finance or climate reparations or for demanding an end to fossil fuels. The two I participated in were organized around youth and Asian identities.

As soon as we showed up, signs were handed out to us, so we could jump right in. One person would take point on the mic, explaining the purpose of this demonstration, sharing chants with the rest of the rally, and passing off the mic to others to share their stories. Stories that showcased how the people experiencing the very worst of climate change are the least responsible for it. Sometimes people would jump in to share chants from their own related movements, and I don’t just mean in terms of campaigns, but also cultural songs and dance of political resistance.

The People!

United!

Will Never Be Defeated!

During the demonstrations, I had men touch and move my body without my consent. There were men who would repeatedly move me out of the way to get a closer shot of someone else, or raise a camera directly into my face, or grab the sign I held beyond my reach, only to hand it back to me once their colleague was done taking a photo of them. Even while feeling empowered to be in solidarity, I marveled in the ways our actions seemed to be interpreted as a photo op.

Despite being surrounded by cameras, I heard some organizers reflect that they themselves were unable to take any photos because reporters and passersby were blocking organizers from getting to each other. They would just have to hope that they’d get photos later. As someone without mainstream social media personally, I still found pictures of me online.

No more blahblahblah

Loss and Damage Finance Now!

At one panel, an executive from a Big Tech company expressed:

Maybe it’s a good thing that the conference is taking place in countries like Egypt, and should continue to do so. It forces global leaders to see what it’s like on the ground and it will motivate them to actually take action.

Unfortunately, I cannot help but disagree. The Global North already takes their chances to travel to the Global South as an opportunity to engage in the tourism economy (or even the more philanthropic “voluntourism”) that perpetuates the commodification of cultures and is not doing anyone favors. As we see this conference stress test the capacity of Egypt to respond to the high expectations of leaders and delegates from the luxuries of “developed” countries in the Global North, I would be pained to see this repeated again and again across the Global South. Frankly, people from the Global South and reconstructions of the Global South in the Global North have been stating clearly for decades what the circumstances are like as a consequence of climate change. Instead of coming into our homes and gawking, listen to us. These people do not exist to perform as trauma porn just so that the Global North will take us seriously.

Pay Up!

Pay Up!

Pay Up for Loss and Damage!

It’s true that developed countries are the most responsible for climate change, that’s why they’ve been given the responsibility to take leadership in reducing their impact. However, so long as they remain accountable to themselves, the conversations will keep centering their issues foremost conference after conference. I believe that if instead, the so-called “developing” countries, countries treated as “poor” when we are rich in our own ways, were centered in leadership, then there would be no COP27. We might have resolved this all a long time ago.

You giant carbon emitters, you owe us this money!… Let’s not go to COP28 with the same conversations! For how long are we going to talk about climate finance? Every COP, every COP we get and have conversations, same conversations! Can we get done with climate finance on COP27, please? Next year, COP28, let’s have other conversations! We can’t keep talking about the same. We are wasting time, resources, money, everything, we are wasting a lot of time. It’s overdue. This money will help a lot of countries that have a lot of loss and damage. Please pay up today! Thank you.

Transcription from the demonstration

Also, make sure to check out the Indigenous Environmental Network’s Key Takeaways on Climate Finance:

Climate change will not be solved by financial mechanisms – they are a cause of it. Real solutions foreground Indigenous Peoples and Mother Earth, not financial institutions.