Emily Kerimian ’25, Swarthmore College; Honors Environmental Studies major and Honors German Studies minor

Before arriving at the Conference of the Parties-29 (COP-29), I had a fairly clear idea of what I would see in this international and multilateral climate change conference hosted by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): busy, tense negotiations, where every word, comma, and bracket is scrutinized, side events and press conferences, where adaptation, mitigation, and loss and damage are discussed at length, and pavilions, where delegate Parties (i.e countries) host events to show off their progress in achieving their goals and discuss future ambitions and other non-Party groups can educate visitors about their role in combating the climate crisis. I even expected to see protests, even if in a diminished form. All these events take place in the Blue Zone, where you need a badge, indicating your name, affiliation, days of access, and classification. I attended this conference as an observer, a role meant to inspire negotiators to action, serving as the general public’s eyes. My badge only became active on Tuesday, November 19th. Thus, on Monday, November 18th, I entered the Green Zone.

The Green Zone is an area of COPs that does not host negotiations. Instead, it features rows upon rows of booths set up for varying purposes. Typically, at these booths, you can find activist groups, or non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and spaces to interact with highly-informed people from all walks of life. This year, at COP-29, I saw many booths dedicated to businesses. One particular business that stood out to me happened to be SOCAR, the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan. The prevalence of business in the Green Zone disheartened me. However, I continued to explore the Green Zone, seeking for something to re-inspire me.

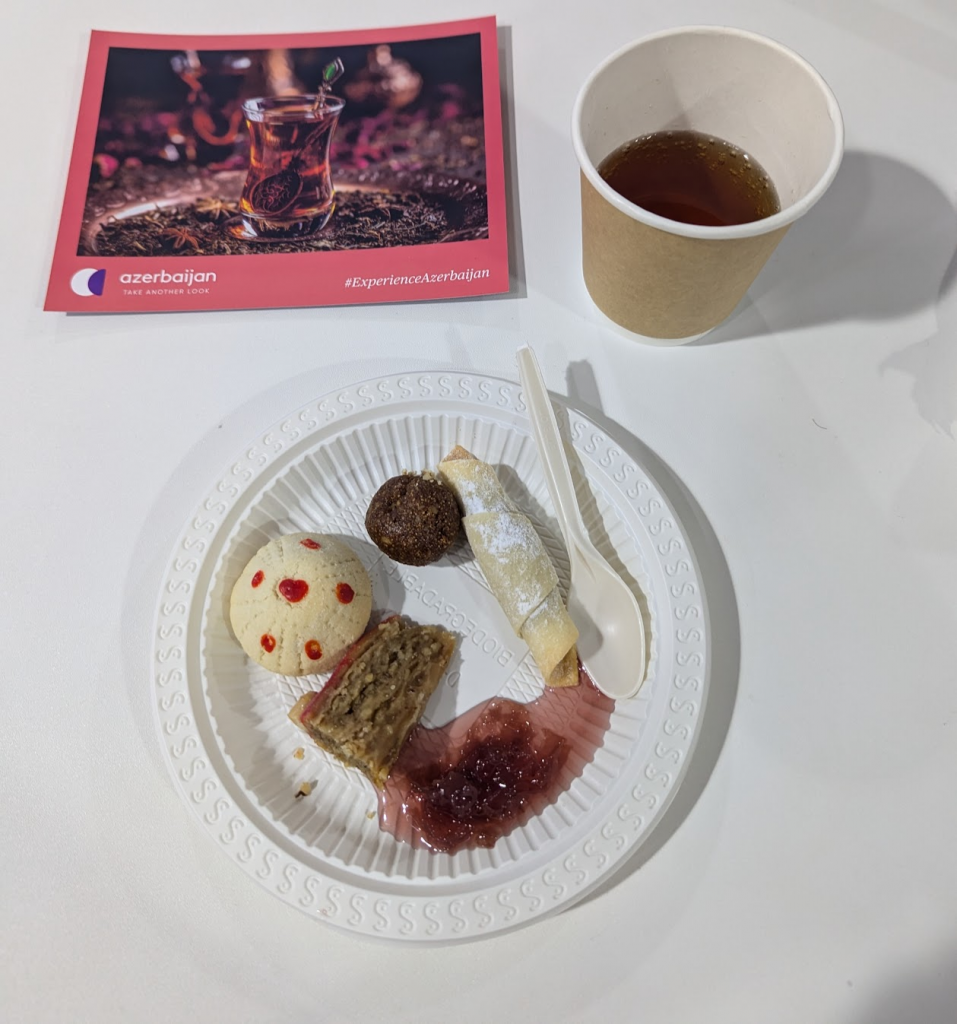

While searching for the Art Pavilion in the afternoon, I stumbled across the “Azerbaijan” area at the center of the Green Zone. When I inquired about the Art Pavilion at the information desk, I was informed that there was indeed art and demonstrations occurring in the Azerbaijan Pavilion of the Green Zone. The kind volunteer steered me to the other side of the space, where I was handed a complementary cup of tea and a plate of traditional Azerbaijani sweets. Having not eaten since breakfast, I was grateful for the respite. After I finished my unexpected treat, I floated from demonstration to demonstration, absorbing more culture and kindness. Artisans from across the country, including remote villages, had been brought to the conference to share their talents and traditions with the visitors of COP. First, I learned how to make a shabaka, or shebeke in Azerbaijani, a stained-glass window. These intricate, lattice wood and glass structures captured my eye, but proved to be difficult to assemble. However, the artist was patient, guiding my hand, allowing me to mirror his work.

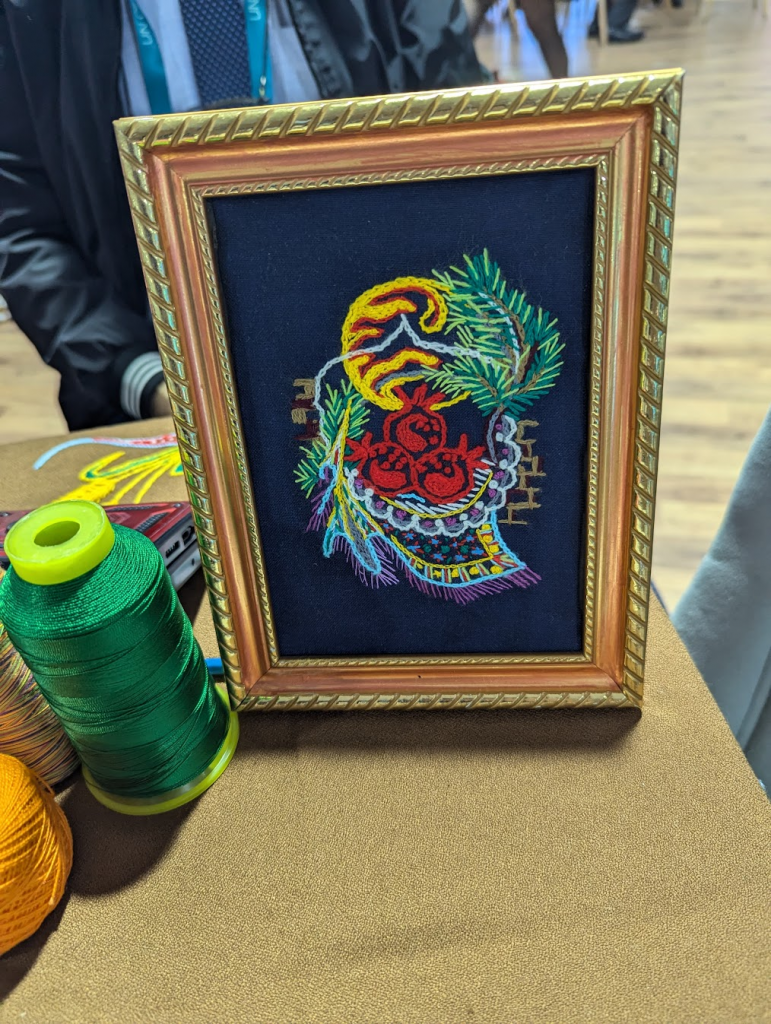

After thanking the man, and taking a quick picture of my handiwork, I approached a table covered in several detailed embroidered canvasses. Takelduz, or the art of embroidery, is a long-standing folk art tradition in Azerbaijan. Back in the United States, on Swarthmore’s campus, my best friend, who is incredibly gifted at embroidery, would have been delighted. I, meanwhile, timidly approached the table, to admire the craft. The woman making quick stitches beckoned me, and began to show me how the pattern takes shape. I copied her, falling into the easy rhythm, making the outline of her newest design take shape. This is a skill that I can see myself adapting into my own life, as it offers a great chance to be deliberate and contemplative, especially when topics, like the threat of climate catastrophe threaten to become overwhelming.

Next, I observed a woman weaving a rug by hand. She sat at a low bench, hands fluttering over a loom with a third-of-the-way finished rug. The volunteer returned, to let me know that the finished rug would take months, if not a year to complete. To me, the process of making a complex silk rug requires a similar brand of patience and faith that is necessary when waiting to see the outcomes of climate negotiations. Inspired by watching a silk rug being woven in real time, I made sure to bring home a small traditional rug for my parents, who to this day lament about passing up an opportunity to buy a large, shimmery silk carpet on a trip to Turkey.

In the same vicinity, I saw village women, darning with spools of wool. Again, I relied on the translation skills of the volunteer. She explained to me that in more remote areas, outside Baku, the capital, families make their own clothes out of wool. They work in phases, gathering the fibers and threads, spinning them into wool, dying that wool, and finally making items of clothing. In a world where the allure and ease of purchasing fast fashion abounds, seeing this strong example of reliance on personal skills and local resources made a strong impression on me at COP.

I then noticed that the table where a copper-smith was sitting was vacant. I took a seat and felt the grooves where he had etched a design into the copper. I summoned my courage and attempted to initiate a conversation in Russian. As a third-semester student, I feel my abilities are far from polished, but Russian is the second-most spoken language in Azerbaijan, and I enjoy making an effort to engage with people in a local language, if I am able. The man understood my Russian, and asked me how I learned, which gave me the chance to say that I was a student. While we chatted, I noticed he was working on a small piece. The volunteer looped back to the table to tell me he was making a ring for me. When he finished the piece, I noticed it had “COP-29” etched on it. It is a keepsake that will remind me of the beautiful and impactful time I spent in the Green Zone on my very first day of COP, and the connection I made in my third language.

For my last station, I visited a woman drawing henna. I had never had henna drawn, and the volunteer seemed thrilled on my behalf for my first henna experience being in Azerbaijan. As I watched the woman ink out a delicate flower, complete with leaves, and “Baku” with a heart, I reflected on this portion of my day. I had expected to be inundated with climate and UNFCCC lexicon, and negotiation updates. I did not expect an intimate look at the fascinating culture of COP’s host country. While I do not agree with the government of Azerbaijan, and still harbor mixed feelings about the decision to host COP-29 in an authoritative petrostate that has a recent history of ethnic cleansing, I feel nothing but love and respect for the people who took time and care to show visitors to COP the crafts of their homeland.