By Matthew Neils’ 22 and Ghazi Randhawa ‘22

Hi Everyone, COP26 ended today on a historic note. In spite of its shortcomings, COP26 should go down in history as a breakthrough COP as a lot of countries have shifted their stances and offered compromises for the sake of avoiding a dystopian future. In this flurry of shifting media cycles on every big and small announcement from COP26, we decided to write about an important net-zero pledge made by a very important developing country that has frequently expressed reluctance on climate commitments: India’s pledge for net-zero GEG emissions by 2070.

The recent report by Climate Action Tracker (CAT) shows that the world will likely miss its target to restrict the global average temperature to well below 2℃, let alone the 1.5 degree Celsius by 2050. With the new pledges in the previous week of the COP26, CAT found that the world would rise to be about 2.4 degree Celsius by the middle of this century. Moreover, the current plans against climate change have been criticized for setting very short term goals which would not prevent increases in temperatures above 1.5 degree Celsius.

While developed countries have been rightfully criticized for pushing our shared world to this brink of collapse and low-income, developing, and island countries have been highlighted as the primary victims of the crisis, the rapidly emerging economic giants of BRICs have had an evolving and contentious role in international negotiations surrounding climate action. Their sheer economic growth and rising greenhouse gas emissions are generated by the need to lift their population out of poverty. This need for growth is coupled with their vulnerability to climate change. China and India present an exacerbated version of issues that arise in climate action by emerging economies: a huge growing population, rapid economic growth at the expense of environmental concerns, and extreme vulnerability to climate change induced alterations in the functioning of their earth systems. Their share of the total greenhouse gas emissions has been steadily increasing since the start of 1990s. Yet, their per-capita emissions of GEGs are still quite low in comparison to developed countries that have markedly higher GEG emissions per capita.

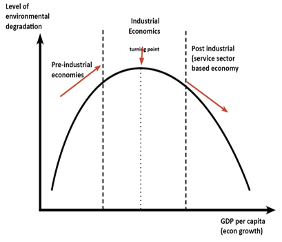

Developed countries have long stressed the trade-off between climate action and development opportunities. This stance is contentious and has led to failure of previous climate action agreements like the Kyoto protocol’s ratification in the US. In view of the evolving science and economics behind climate change, there is a growing consensus that economic development in these countries should not follow the Kuznets curve perspective. The Kuznets curve implies that countries’ tolerance for levels of environmental degradation has a trade-off with development that eventually reaches a peak. After that point, the country’s preference for environmental degradation goes down even as further economic growth occurs and this leads to environmental cleanup. Many countries have shown development and environmental patterns on lines of the Kuznets curve with the most recent example being China. However, with the burgeoning scientific literature on climate change, experience with development strategies, and breakthrough scientific developments, there has been a growing recognition for the dispelling these cycles of development economics and a call for sustainable low-carbon development pathways.

Historically, India has been part of the G77 group in global climate negotiations. Since the first UNFCCC conference in 1992, India’s economy has grown rapidly along with its aggregate carbon emissions and per capita emissions. If corrective action is not taken, India is expected to join the club of countries who single-handedly contribute the most to fueling the climate crisis. Of the four largest emitters (China, the United States, the European Union, and India), India was previously the only emerging economy not to have made a net-zero commitment. As recently as a month before the COP26, India shirked its responsibility for climate action. India’s (coupled with China’s) earlier reluctance for climate action has led to breakdown in negotiations at earlier climate conferences. While India has agreed to the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibility, it has been reluctant to make a net-zero pledge for many reasons.

Firstly, India has been a vocal advocate for the right of developing countries to pursue their development plans. India has instead laid the onus of climate action on developed countries who caused the problem. It has repeatedly pointed to the fact that its per-capita emissions are lower than many developed countries who have caused the problem of climate change. India is a rapidly developing huge country which is not expected to reach its peak population and economy for a long time. India has relied on fast and massive economic growth rates to pull swathes of its population out of poverty. To summarize, India has long believed that it has a lot to lose from climate action which it believes would hinder its economic development strategy. However, new breakthroughs in science about climate change have led to serious concerns about the short term and long term sustainability of any carbon based development in any country. India is no exception to this insight and its vulnerability to climate change has impacted its view on climate change.

Secondly, India has frequently objected to the ‘net-zero’ framing of climate action. Net-zero commitments are often criticized for being hollow pledges in that they do not commit to decreasing carbon emissions. India has instead been more active in pledging better carbon intensity targets for its economy. Carbon-intensity targets aim to increase the efficiency of carbon emissions for running the economy. Carbon-intensity targets are touted by India as a more pragmatic measure of climate action than net-zero pledges. Net-zero emissions have also been recently criticized for being too long-term and not doing enough to prevent extreme climate change in the short term(more than 1.5 degree Celsius by middle of the century). Moreover, the number of countries making net-zero pledges has grown vastly over the past few years and India has been facing pressure to join the club. Moreover, we think that the goals of net-zero and carbon intensity should go hand in hand in development policies. Just committing to increased carbon intensity or net-zero pledges alone would not ameliorate the problem of aggregate emissions of India.

Thirdly, India has been reluctant to cooperate in view of unfulfilled pledges for climate finance. It is a known fact that developed countries largely failed to fulfill their pledges for immediate and long term climate finance they agreed to in the Paris agreement of 2016. This pattern of repeated failure by developed countries in provision of climate finance has caused a trust vacuum. Why should developing countries keep giving leeway and ratchet up their commitments to climate action when developed countries keep on failing to deliver on their promised action? COP26 saw increased activity and relatively more solid commitments and pledges over climate finance. Moreover, we think that climate finance is a thorny issue and its best possible resolution would still be far from the perfect version that many developing countries would want. It should not hold back India in driving up its ambition in climate action and emissions pledges because there is no other option around climate change.

Last Monday, India joined the other major emitters in a neutrality commitment with Prime Minister Modi’s announcement of new climate goals. This announcement represents a major break from the country’s reluctance to make a net-zero goal. Less than a week before the beginning of COP26, India’s minister of the environment expressed skepticism over the value of neutrality commitments. In light of this reluctance, The new ambitions have three main pillars:

The headline goal is for net-zero emissions by 2070. This date is 10 years behind China’s goal of 2060, and 20 years behind the American and European goals of 2050. It also falls behind global calls for net-zero emissions by 2050 in order to keep warming under 1.5 ℃. Although 2070 falls behind this goal, policymakers have indicated that later deadlines among low and middle income countries can be consistent with remaining below 1.5 ℃ of warming if wealthy countries achieve neutrality before 2050. Indeed, increased pressure on wealthy countries is part of India’s climate strategy. Their minister of the environment has highlighted the importance not only of when a country reaches neutrality, but how much they emit before they reach that point, calling attention to the major contributions of wealthy nations and China to global emissions before they reach net zero.

Additionally, Modi made a number of promises concerning the energy sector: an increase in non-fossil fuel generated energy, achieving half renewable energy generation by 2030. There is doubt about whether India can successfully fulfill these commitments given its history with similar goals. For example, the country had a previously-stated goal of 175 GW of renewable energy generation by 2022, but its capacity currently stands at roughly 100 GW and the country is not on track to reach its goal. The new commitment is for 500 GW of capacity by 2030, an even more ambitious increase. Additionally, coal is an important part of both India’s power generation and its economy more generally, with coal mining and coal energy generation accounting for roughly 10% of the country’s Index of Industrial Production. This reliance makes a shift to renewable energy especially politically and economically challenging. India’s attempts to remove language supporting a phase-out of coal from today’s COP26 deal further reinforce this concern.

Finally, the country aims to cut its carbon dioxide emissions by 1 billion tons (compared to business as usual emissions) by 2030 and has raised its carbon intensity reduction goal from 35% to 45%. While these new goals are among the most ambitious announcements to come out of COP26, and the new climate aspirations are an encouraging sign, they may not be enough. In light of the Climate Action Tracker report, India, like other large economies, needs even more ambitious climate goals in order to keep warming below desired thresholds. Climate Action Tracker rates the new plan “Insufficient” (up from a previous rating of “Highly Insufficient”) due to the lack of concrete policy details and the fact that the enhanced pledge still does not place India on track to keep warming under 2 ℃.

Even with these doubts and limitations, India’s commitment is certainly ambitious, and is a noted improvement on previous climate goals and projections. At the very least, the plan represents a major ratcheting up of climate ambition when compared to India’s previous reluctance, and may provide an impetus for similar aspirations in other countries and sectors. If successful, India would achieve a major energy transition in a country currently reliant on coal and oil that could provide both motivation and practical guidance for other low and middle income countries seeking to make similar transitions. The announcement from a previously reluctant party also places political pressure on other large countries such as the United States, Brazil, and China to enhance their mitigation efforts and may have spurred some of the later commitments from these parties at COP26.

As highlighted by Modi and the Indian delegation, much of the success of the plan is incumbent on the delivery of appropriate levels of climate finance. Even with opportunities for technology transfer and leapfrogging that could allow for low-income pathways to neutrality, such a transition is expensive, and requires major up-front investments that can be difficult to finance. Additionally, climate finance is an important area to support environmental equity. While India is a major net emitter, its per-capita emissions remain far below those of wealthier countries. Therefore, expectations of major emissions reductions without proper support from these countries are both financially unfeasible and do not properly align with climate liability and responsibility.

India’s net-zero goals thematically align well with much of the other news coming out of COP26. They are a definite improvement over previous business-as-usual attitudes, but there are serious concerns about implementation and they remain insufficient to meet more ambitious climate goals. The way that they will be most effective is if pressure is put on other countries such as the United States not only to support low and middle income climate transitions, but to similarly ratchet up ambitions for domestic energy transitions. As climate-conscious citizens it is important to promote the messaging that commitments such as India’s are not an end-solution to the climate crisis, but rather a positive acceleration of climate ambitions that must continue in order to avoid the most harmful outcomes.