Greetings everyone from Glasgow, Scotland!

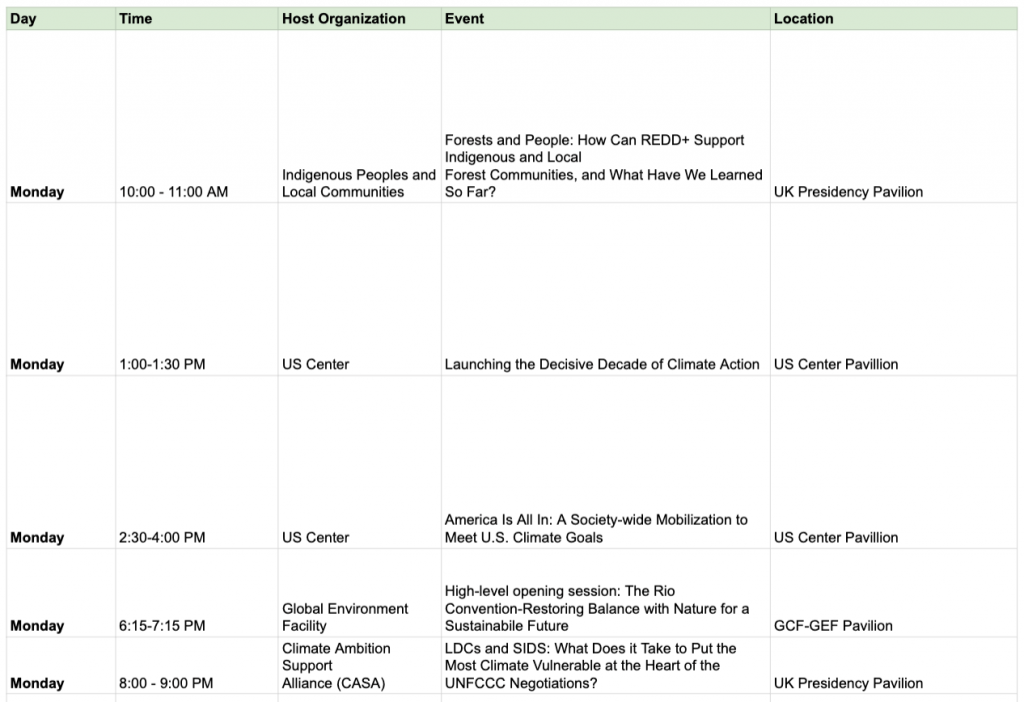

While the Swarthmore COP Week 1 Delegation (Daniel Torres Balauro, Alicia Contrera, Clare Hyre, and Melissa Tier) got to an early yet slow start on our first official day, our days’ pace immediately changed as soon as we entered. Although it is still quite difficult to develop a daily itinerary given the quick changes that occur, insider info you get on the ground, and informal meetings, here is a list of the events that I had planned to do today.

Surrounded by fellow observers, national delegates, and heads of state, we ventured into the “Blue Zone,” where country and organizational representatives host events ranging from topics showcasing their current advocacy, research, and efforts. (Side note: The difference in country’s funding was quite apparent just by comparing country pavilions like that of the United Arab Emirates’ versus Tuvalu’s).

United Arab Emirates (UAE) Pavilion

Tuvalu Pavillion

Given my personal interest in exploring the power imbalance between “developed” vs “underdeveloped” nations, I was intentional in attending events that expanded on this exact topic.

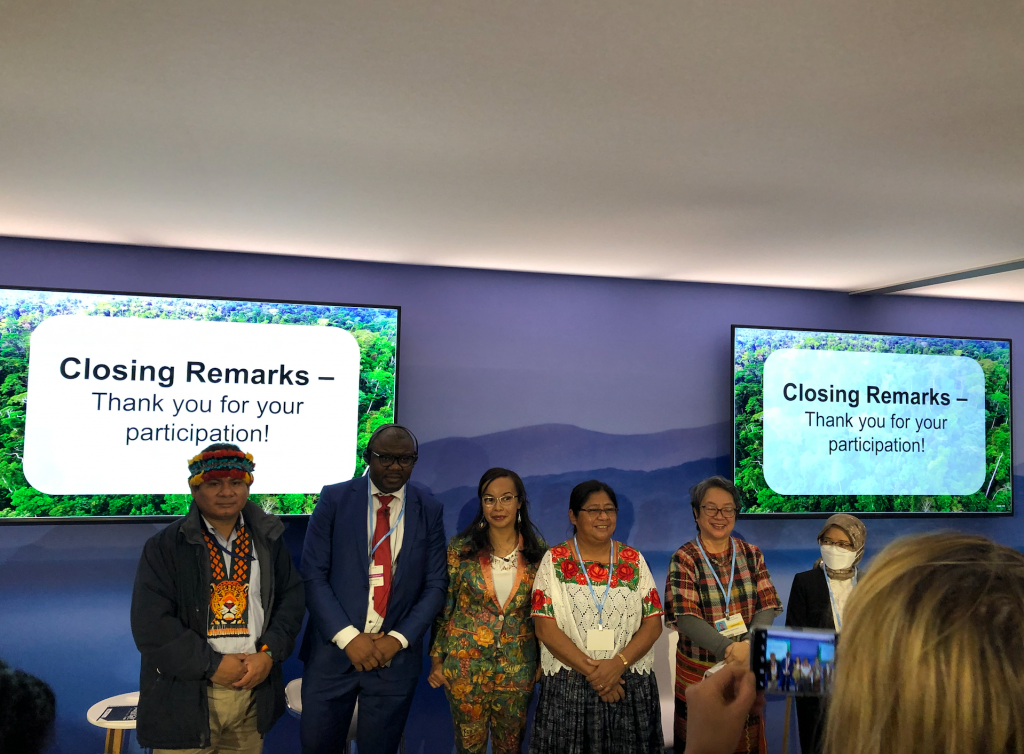

For example, my very first COP event, entitled, “Forests and People: How Can REDD+ Support Indigenous and Local Forest Communities, and What Have We Learned So Far?,” was paneled by Indigenous leaders and activists from around the world. Present were Tuntiak Katan, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, Dolores de Jesus Cabnal Coc, and Raymond Samndong who discussed their efforts in ensuring that REDD+ (Reducing emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) Framework to center Indigenous strategies in its implementation. They highlighted the fact that despite financing Indigenous peoples (which has its own complications), policy-reform (in other words, collaboration with governments) must be the utmost priority. In Swarthmore fashion, I pushed this answer even more and asked: How do we continue this sort of collaboration with governments like that of Brazil’s and the Philippines’s who have been explicit in undermining the rights of Indigenous peoples? While they were not able to fully answer my question due to time, they explained to me that the enhancement of internal “capacity-building” in Indigenous communities is one way to address this challenge — and thus, we must find ways to strengthen our collective action.

After the panel, I was approached by former UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Victoria (Vicky) Tauli-Corpuz, who chatted with me about environmental activism in the Philippines, and the dangerous conditions present as many activists are declared by the government as “terrorists.” Our conversation ended with us exchanging contacts, and an (over-excited) Daniel taking a selfie with Vicky.

Later on the day, I joined the rest of the COP delegation for two sessions at the United States (US) pavilion respectively titled, “Launching the Decisive Decade of Climate Action” and “America is All in: A society-wide Mobilization to Meet US Climate Goals,” where representatives talked about the important role of the US in addressing the climate crisis, especially after its previous withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. In these sessions, we were joined by many notable folks including, Secretary of State Tony Blinken, US Climate Envoy John Kerry, National Climate Advisor Gina Mccarthy, and Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

While it was great to hear all of these officials speak, the rockstar of the night was Indigenous youth activist: Sam Schimmel (Kenaitze Indian/Siberian Yup’ik). Schimmel talked about his Indigenous community in Alaska, and recalls a story where his father explained that the ocean is not merely a body of water, but their “grocery store.” Schimmel is getting at his community’s heavy reliance on the oceans, underscoring the importance of the preservation of their natural resources as a way to sustain their livelihoods and culture.

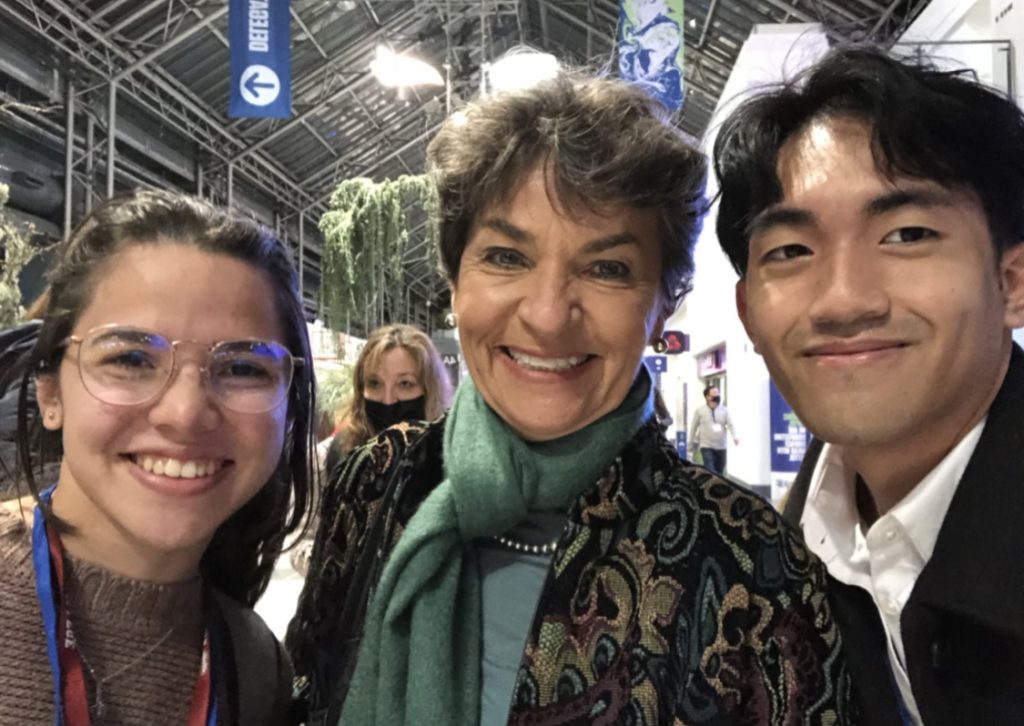

To top my very first day at COP26, Alicia and I had the chance to informally meet former Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and Swarthmore alumna Christiana Figueres ’79. It was nerve-wracking to approach her, but I’m so glad we did since she met us with so much excitement and imparted to us some words of wisdom and advice (whatever that advice was will be kept to me and Alicia for now).

(I promise we wore our masks the entire time.. except for this moment, haha)

It was so powerful and valuable to me to be able to be in a space to discuss and learn about these issues. While efforts have been made for the inclusion of traditionally underrepresented voices within the international climate regime, I remain cognizant of the flawed power structures that puts the future of these nations in the hands of those that continue to threaten it. Throughout my next couple of days here at COP26, I hope that I am able to continue learning from folks around the world aiming to resolve these important issues.

Thank you for sharing such important reflections, Daniel, and wonderful that you connected with Vicki Tauli-Corpuz. How exciting that you and Alicia met Christiana on your first day at COP-26. As we learn in Ecofeminism(s), women are the bada** movers and shakers in the global climate justice movement!

Daniel! I am thrilled that you are attending COP-26 and that you are immediately finding people and ideas of such relevance to your long-term interests and commitments. Thank you for sharing your experience and photographs (Christiana Figueres ’79!).

Potential questions for the nations at COP26:

Due to environmental degradation (caused by climate change and other active human activities), the natural habitats of several animals have been reduced, resulting in animals and humans now living in closer proximity to each other. This is potentially the reason why SARS-CoV-2 was able to originate in bats and then mutate to then be able to infect humans, who are then able to infect other animals. Considering that the COVID-19 pandemic will not be the last pandemic we will face with animal origins, how are nations going to take responsibility for animals on their land and take a preventative approach to such pandemics in the future with both the safety and benefit of the animal and the human in mind?

Based on this advocacy for interconnectedness between non-human species and humans, how will nations also work to establish coalitions between distinct groups (e.g. countries with greater resources with countries with less resources, able-bodied people with the disabled, particularly the immunocompromised, the elderly, and children, etc.) on their land so that, if pandemics were to occur in the future, the act of leaving certain groups behind (such as leaving poorer nations with fewer vaccines or forcing immunocompromised people to stay home) does not occur again?

When looking at environmental issues through a disability framework, we are forced to grapple with the reality that human health and environmental health are deeply connected – environmental pollution causes a great deal of physical harm to human communities, especially marginalized communities and communities of color. Sunara Taylor writes that “we need to rethink the separation of human health from the health of our environments and social welfare systems.” We are curious if there are conversations at this conference about the “othering” of the environment and the ways to address these problems?

Thanks Zoe, Gian, Hannah, and Emily for this question.

I fully agree about the deep interconnectedness of human health and the environment. To further add to your point, I would even argue that the emotional trauma of losing your culture (especially when its so connected to your land) is also even more important to consider.

While I will be missing the day focused on “Nature,” (side note: each day has a theme) where I would suspect that would be most closely related to, I have been able to attend a session that briefly touched on that. It was at the World Health Organization pavilion where they really talked about this necessity to end animal and meat consumption. I’m often very skeptical of this “everyone must be vegan in order to save the planet” approach for a couple of reasons. 1) it fails to understand the way that these types of food can be connected to a certain culture 2) it shifts the blame to the individual.

I was able to communicate these concerns, and they replied to me that they were “targeting the global north” while also focusing it really on factories excessive production. I am inclined to agree and be okay with this statement, but wished I had a deeper discussion about this issue.

All this to say that yes, there are spaces where these are being discussed. In higher-level negotiations, I am not too sure.

Hi Daniel, thank you so much for this post. Here’s a few questions we have been thinking about: How are you utilizing your knowledge, resources, and agency at COP26 to address the possibility that COP26 may not accomplish much, if anything?

What conversations are you not seeing that you wish were taking place?

What are you bringing back to Swarthmore College? What do you want to bring back?

What can students at Swarthmore do with the knowledge that you’re learning?

Do you see moments where leaders are revealing vulnerability?

Do you feel that you are affected by the culture(s) present at COP26?

Hi Katie, Simone, and Chris,

How are you utilizing your knowledge, resources, and agency at COP26 to address the possibility that COP26 may not accomplish much, if anything?

– I am cognizant (and have written alot!) about the very limited roles that observers (this is our delegation’s status) have in these spaces. For me, my goal has always been one and the same: support activists and community leaders that are often underheard and underserved in whatever capacity (whether this is just connecting with them, seeking out ways I can help share their message, etc.) Just using both my personal experiences and the critical knowledge I’ve gained at Swat, I’ve made it a mission to always ask questions of concern when I have the chance to. The very interesting thing about COP26 is that while it’s such an important space because deals happen every single hour — we won’t fully know whether or not they’ll actually follow it. It’s this uncertainty that bothers me… and am still trying to grapple with.

What conversations are you not seeing that you wish were taking place?

Hm, I am really interested in this concept of climate reparations as an approach to address the historical and present injustices occurring against frontline communities. There have been spaces to talk about topics like this, and at the more high level sessions, this directly relates to “loss and damage” (which I believe will be more discussed in Week 2) and “climate financing.” I think it’s definitely being talked about, but the magnitude of the actions that I would like it to reach is not being talked about.

Along this, I’m really interested in climate-induced migration. And I wished there were more spaces to think more about that as it is such a key issue affecting all nations. (happy to expand more on this if anyone is interested!)

What are you bringing back to Swarthmore College? What do you want to bring back? What can students at Swarthmore do with the knowledge that you’re learning?

I’m really that through this blog, teach-ins, the post-cop discussions that we’ll have, and other efforts that we’re thinking about.. it will help spark the discussions of understanding our role within these discussions. Not even just as a Swarthmore student, but just as an individual. I have my own personal stakes in here as being from a South Pacific island, and I’m hoping to start an initiative back in my community to address the vast inequalities within these important environmental conversations. And if I could help inspire and/or work with a Swat student who is deeply interested in doing this work, I will use my knowledge to do just that.

Do you feel that you are affected by the culture(s) present at COP26?

Absolutely. I was able to be briefly connect with the small delegates from various Pacific nations… and just actually hearing a couple of them say that they don’t feel that they have equal influence in these discussions and that their main goal is just to raise awareness is deeply moving. As I noted, I am even more impassioned to do a lot more work back in my Pacific community to address these issues.

Dear Daniel and Alicia,

We appreciate your analytical framework and commentary on the proceedings thus far. We had a few questions surrounding the nature of critical engagement with communities. If you might have some insight on that that would be helpful:

How representative are the delegates of the citizens they are representing? In your opinion, do they express sentiments of the civilians affected by climate change, or do they speak more for businesses/the government they speak on behalf of?

Is there any information on if these countries are keeping to the commitments they made in previous meetings? When the meeting begins, is there a discussion about any updates or changes/progress made within the year?

How much of the ‘swag’ or official conference materials are used? How might it be possible to conduct a Zero Waste conference?

Thank you all!

Alyssa, Kayla, Tyler, and Veronica

Great questions. I don’t know every nation’s delegates, nor am I familiar with their specific goals and community needs, but I can cite one example that I hope can be helpful. My example is this year’s Philippine delegation, who unlike previous years, have decided not to include two notable global climate justice activists (Tony La Viña and Yeb Saño) that has represented the nation for years. On top of that, they also do not have negotiators with extensive scientific backgrounds, but rather it is filled with many finance officials (which is absolutely important, of course, but really shows their priorities.) This is not surprising given the background of Philippine President Dut*rte, who is a big advocate on ensuring that wealthy nations *pay.* Lastly, to my knowledge, there is no Indigenous stakeholder as part of the party. Honestly, the Philippines isn’t unique in this strategy and exclusion of these important stakeholders .. and just really shows what the nation’s priorities are as they attend these conferences. While I believe that my point still stands, I do think it is important to consider that some countries cannot afford to send delegates (unlike the United States who I believe has 300+ party members) and again, just shows their strategies in these discussions.

In terms of information on commitments, this is definitely an important topic as the point is to assess their progress. But just thinking about the lack of accountability mechanisms in place and uniform progress measurements, it would already just be hard to tell. However, I’m sure that more information will come out in the next couple of days. This also relates to your next question about what happens when the meeting begins. Most of these negotiations have been strictly for high level government officials only so we cannot fully report on what actually occurs in there. But I am told that we’ll have access to ~some of the plenaries (where they hold negotiations) tomorrow. And I’ll stay tuned to write about it if given access!

To answer your last question, we were actually not given a lot of “swag” besides like a “hygiene kit” which included a mask, sanitizer, wipes, and reusable bottle. The venue is so large that I can’t fully explain all of their efforts in making the venue zero waste, but a couple of examples include basic efforts such as, providing reusable cups/mugs, lots of bins to sort waste, etc. On top of that, I am familiar that they have some partnerships with organizations that do a lot of zero waste work which sort of help them in different aspects. I’m not fully sure about any statements from the UNFCCC regarding this, but will keep a look out and return to reply if I get any more information. (UPDATE: https://ukcop26.org/the-conference/sustainability/ they’ve updated the site to include this!)

Update: Climate finance commitments are published and can be found here: https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Table-of-climate-finance-commitments-November-2021.pdf

In the context that COVID-19 has impacted different nations disproportionately, what is being done to recognize the inequalities that exist at this conference, such as who in attendance has been able to have access to the vaccine, why were they able to access it, how did they access it? Furthermore, while we are all in or in relation to communities with those who are immunocompromised and certain groups that have always been put disproportionately at risk, be it COVID-19 or other global pollutants: what aspects of the conference ensure that we are able to achieve what would not have been possible had the conference not taken place?

Are there spaces to engage with spiritualities at this conference? How are the cultural relations with nature incorporated into the dialogues of decision-making?

Even before COP26, there already existed so many inequalities in terms of representation. And as your question gets at, it’s even more complex this year given vaccine inequity. I know that just a couple of months before COP26, the UNFCCC in partnership UK announced that it was offering vaccines (not mandatory) to all registered COP26 participants. For those who come from “red-list nations,” require managed quarantine requirements, and/or faced some sort of hardship due to the pandemic, the UK worked to fund their stay in the country. On top of that, everyone is required to take a lateral flow test before entering the conference — which they also funded.

While these efforts are great, there still remains so many issues in representation. For example, Pacific nations are deeply underrepresented (more than before). And with those Pacific nations who were able to send a couple of delegates like Samoa, being away from their island home will be a lot longer than anticipated given that they are leaving to represent the island and sacrificing over a month away due to border restrictions created by the pandemic. This is all this to say that, at its core, COPs has always had a problem in representation… it’s just a lot worse now with the pandemic in the mix.

As for your second question on assessing what aspects of the conference ensure that we are able to achieve what had not been done before, I would say that COP26 is especially unique given that its a revisitation on all of the national commitments (from the Paris Agreement) after five years. It is also the first year that the United States (a major player in these negotiations) have joined back officially. On top of all of this, we have the discussions of the $100 billion climate finance fund. Besides this being a test for international cooperation, I believe that the conference is necessary given all of the crises we’re facing and this being a way to see which if “developed nations” will address their huge responsibilities.

Lastly, I would say that there has definitely been a couple of sessions in the pavilions where they’ve centered the interconnections of culture and nature. I think that over the years, there has been a general recognition that many communities (especially Indigenous peoples) are deeply affected by the climate crisis given these interdependency with the environment. Yet, I believe that one of the biggest challenges is just … what would nations do with that information? You can recognize an issue but not do anything meaningful about it — which is what many countries have historically done. It’s an issue that I’ve heard being raised a lot over the last two days, and I’m hoping that we can actually see this issue being heavily considered in the high-level negotiations.

In our Environmental Justice class at Swarthmore, we’ve been discussing mitigation versus prevention approaches to reform and how they can influence the goals and outcomes of environmental policy-making.

COP 26 was inaugurated around the idea that we are nearing the threshold of a climate catastrophe and an environmental crisis is impending, but not yet here. This projection dissociates policy-makers from our current reality: communities across the world are facing consequences now due to a reliance on mitigation strategies and policies which outline a ‘tolerable’ level of contamination.

Environmental justice researcher and activist Max Liboiron explained the threshold theory of pollution in their book, Pollution is Colonialism. “State-based environmental regulations in most of the world since the 1930s are premised on the logic of assimilative capacity, in which a body—water, human, or otherwise—can handle a certain amount of contaminant before scientifically detectable harm occurs” (5).

It seems that past COP conferences have operated under the goal of staying within this flawed ‘acceptable’ range of harm. But who decides how much harm is acceptable? And who is at the receiving end of this harm? Privileged people decide who has the right to pollute, while the harm is delegated to marginalized/underprivileged groups, deemed “sacrifice zones.” This is inequitable and unethical. Instead, how can we challenge the current definition of what is acceptable and craft a new narrative centered around the notion that no level of environmental harm should be tolerated by or forced upon any communities?

We’ve studied these concepts on a theoretical basis and on a local scale in Chester, PA. We’d be interested to hear more about your conversations with activists and leaders on a global scale representing communities that are being affected by international policies (e.g. cap and trade, carbon offsetting) which perpetuate power imbalances and legitimize the threshold theory of pollution.

Hi Daniel,

Reading your post about hearing from and working with Indigenous communities and hearing from Professor Di Chiro about the ways Indigenous nations are often unrecognized by the UN framework has me thinking about the concept of glitch feminism. Glitch feminism posits that because of the way cyber spaces are built to understand gender along a strict binary, queer and non-white bodies are unrecognized and thus glitches within the system. This is a harm because queer and non-white people cannot access or are critically underserved by certain systems, but also an opportunity. Because they are a glitch, there is an opportunity to subvert and operate outside the oppressive systems.

I wonder if you see this at all applying to the way Indigenous nations go largely unrecognized as legitimate players on the international stage. While the COP is intended to be a common space shared by various international actors, it seems that are still divisions within the COP. Are Indigenous voices being heard and heeded by international leaders from wealthy, powerful nations (i.e. the countries largely responsible for environmental destruction/genocide)? What tactics are Indigenous peoples using to make sure their voices are taken serious and “breaking-into” spaces where they have the chance to be heard by people with institutional power? Is the non-recognition of nationhood in any way an opportunity?

Thank you for asking the questions you’re asking and making your presence felt.

Be well,

Chris