by Eder Ruiz Sanchez ’25, Sociology & Anthropology and Spanish

Upon our arrival to Baku for COP 29, it was clear the city was prepared to welcome over 50,000 attendees. The airport displayed banners, posters, and staff in COP-themed uniforms. Electric powered shuttles and newly introduced electric taxis also bore COP 29 labels, cementing Azerbaijan’s role as the global focus for climate discussions. However, soon after leaving the airport glamor, I saw an oil drill hidden behind some trees. Then, I saw another one in the center of a neighborhood. And several others in neighborhoods and on the side of the roads. This situation undeniably highlighted Azerbaijan’s status as a petrostate hosting a climate conference.

This year’s COP follows COP 28, held in the UAE, where a spectacle of flashy tech was coupled with a major commitment to the “beginning of the end” of fossil fuels. At the same time, the UAE stands as a major oil producer and human rights abuser, undermining not only its credibility as a host but the credibility of COP as a whole. Notably, 2023 was the hottest year on record and 2024 is on track to top that record. A year later and nearly a decade after the Paris Agreement, fossil fuel emissions are projected to reach new record highs. Climate skeptics, like Javier Milei in Argentina and Donald Trump in the U.S., have risen to power, threatening the global climate commitments made thus far. Additionally, reports came out revealing that the COP 29 CEO, Elnur Soltanov, also a board member of SOCAR (Azerbaijan’s state oil company), reportedly used the event to secure fossil fuel deals. In the lead up to COP 29, many Azeri climate activists, economists, and political opponents were arrested.

After studying the UNFCCC frameworks earlier this semester, I felt prepared to engage with the COP processes. However, an increasing amount of information revealed the façade and greenwashing that COP enables for countries like Azerbaijan to do. My skepticism, however, wasn’t directed at the will of the people participating in COP but at the frameworks that allow petrostates and human rights violators to host such events, as well as allow an increasing number of fossil fuel lobbyists into the venue.

Despite its flaws, COP remains a vital space where hundreds of environmental defenders and climate justice activists—particularly those from the Global South and most effected by climate disasters—come together. They recognize the imperfections of host countries, COP frameworks, and innate slowness, but also view COP as an opportunity to organize, build capacity and solidarities, and use the global spotlight to draw attention to their realities. Entering COP, I experienced a mix of emotions, balancing these contradictions with a strange sense of anticipation.

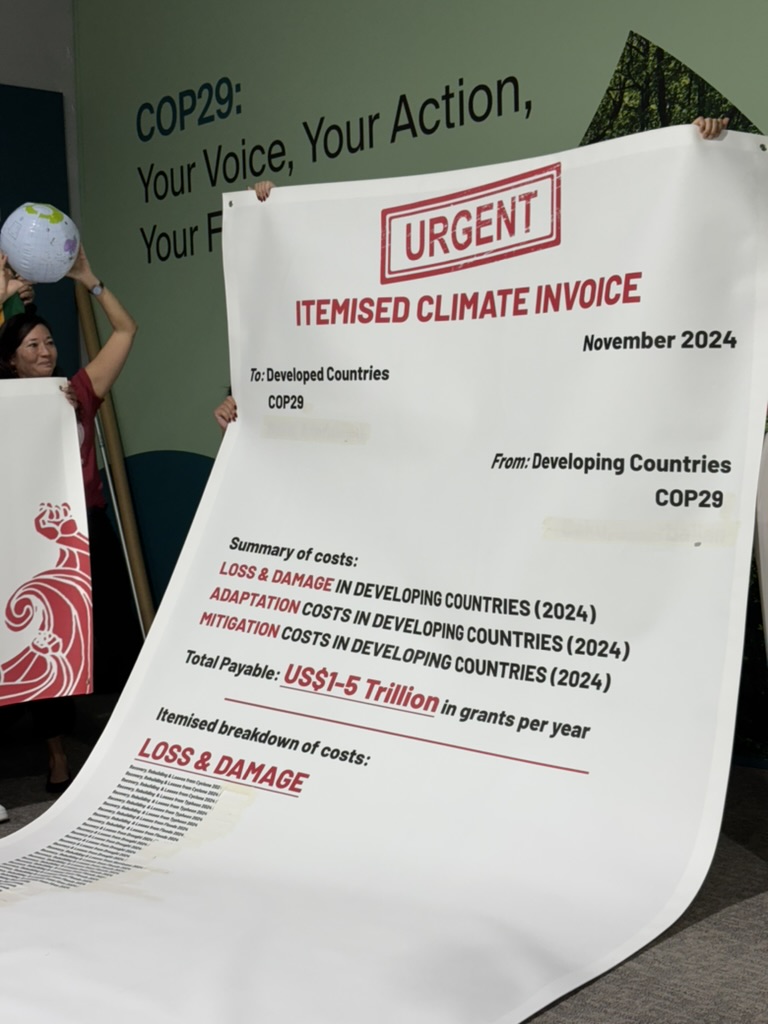

At the opening ceremony, COP 29 President Mukhtar Babayev urged for enhanced ambition and action for climate finance, the mobilization of financial sources for developing countries all ranging from public to private sector contributions towards a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). While the previous NCQG was $100 billion (set in 2009), the acceleration of climate change disasters on developing countries has experts and activists’ expectations of the NCQG being in the trillions. Babayev also acknowledged that current policies are leading us to 3ºC warming, if not more. Despite this, the adoption of the agenda was significantly delayed to later in the evening, stalling negotiations and wasting valuable time.

Day 2 and 3 featured the World Leaders Summit. Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s opening speech further underscored major contradictions. Criticizing “Western political hypocrisy” over Europe’s increased reliance on Azerbaijani oil and gas since the start of the Russian-Ukraine war, Aliyev doubled down on framing natural resources as god’s divine gifts (“gifts from God”), defending fossil fuel extraction, saying “we must also be realistic.” His tone also began to resemble that of authoritarian global leaders calling out “fake media” and took on a dissenting stance against those boycotting this year’s COP. I was even more disturbed when suddenly the plenary and overflow rooms broke out with applause following this statement.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres followed and captured the urgency, warning, “The clock is ticking. We are in the final countdown to limit global temperature rise to 1.5ºC.” Acknowledging the increasing global wealth inequality and it’s connections to climate change, Guterres said:

“This is a story of avoidable injustice. The rich cause the problem, the poor pay the highest price. Oxfam finds the richest billionaires emit more carbon in an hour and a half than the average person does in a lifetime.”

Climate change is inherently tied to the wealth inequality of capitalism. Those in the Global South, as well as individuals of lower socioeconomic status in the Global North, disproportionately bear the consequences and lack the finances to rebuild and invest in adaptation efforts. In other words, climate change doesn’t affect everyone equally—we are not all on the same boat. Throughout the evolution of the UNFCCC, the discourse has focused on the potential threats posed by climate change. However, for many marginalized communities, these threats are not abstract and have been manifesting itself as daily realities of violence and the loss of life and alternative worlds.

Given that COP29 is the the “Finance COP,” it is crucial to connect the concentration of wealth among billionaires to climate change. Wealth is heavily concentrated in the hands of a few. The link between climate justice and economic justice is clearer than ever. Addressing climate change requires confronting the systemic mechanisms that allow the wealthy few to amass emissions-intensive wealth at the expense of the many who endure the consequences. This injustice is a form of violence on the behalf of the wealthy few (and the systems that enable this situation to occur) that views the rest, particularly the Global South, as disposable.

My goal throughout week 1 was to attend 2-3 negotiations on adaptation per day. I often felt confused, unsure on whether I was misunderstanding the process or if there was a lack of progress. Daily reports, along with the frustrated expressions on faces of negotiators and observers, confirmed my observations: there was a clear lack of action. At one point, I heard crickets, literally.

Regardless, it was valuable to witness firsthand the dynamics of negotiations. In the hallways, you could see negotiators huddled together like a sports team, strategizing their approaches. During one session, the African-Group called for a five-minute break to regroup, and suddenly, around 50 people gathered in the corner intensely discussing how to proceed.

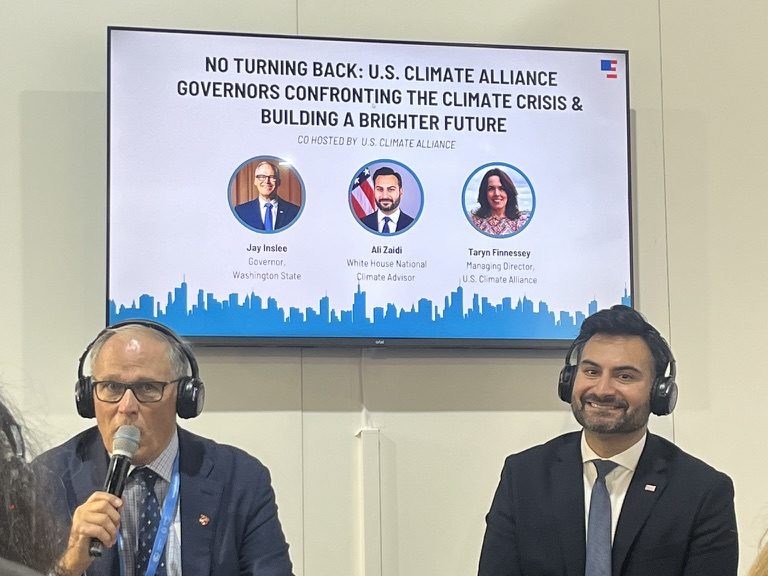

At the same time, it was clear not all negotiators were equally active. In an event at the Ocean Pavilion titled “Ethical Horizons: Navigating Climate Intervention and Solutions” with Axel Michaelowa, Margaret Leinen, and Alia Hassan, they highlighted the capacity gaps in the Global South. Although the conversation was focused on technology, Hassan explained how the gaps in technology are also mirrored at COP in how some delegations are stretched thin, running between sessions due to their small size and others simply lack the capacity to defend their countries’ positions effectively. Despite being agreed upon, many agreements at COP result in developing countries compromising to countries with more power who do not have the same urgency as those already being affected by climate change. The adaptation negotiations I attended were largely dominated by the US, Australia, and African Group, while many remained silent.

Seeking further meaningful engagement, I turned to other pavilions, where I found the Indigenous Peoples Pavilion. With four booths offering live interpretation ranging from Indigenous languages to Portuguese, the small pavilion space consisted of a vibrant energy of love and solidarity, despite being at the forefront of climate change disasters.

Here, panelists highlighted inequities in COP, where the Global North enjoys larger, better-equipped rooms, while marginalized groups fight for inclusion. However, they made it clear that being present is not enough but what matters is the capacity to advocate effectively. Namely, language barriers further exacerbate inequities, as English dominates and UNFCCC jargon often excludes those most impacted by climate change.

An event titled “Decoding UNFCCC Language” that I attended, provided a collaborative space to address these issues while fostering connections across linguistic and cultural differences. Through case studies and group discussions, participants—including activists, scientists, and lawyers—demystified technical terms. Facilitators encouraged participants to pay close attention to the verbs and diction being used in the writing of texts at negotiations, particularly texts that assert some sort of obligation, as the use of certain words can weaken agreements. The event ended with a chanting of “intergenerational climate justice” in every person’s native language.

One of the most memorable events I attended was on Indigenous perspectives on carbon markets titled, “Carbon trading for whose benefit.” At the event, Ghazali Ohorella, the lead Indigenous Peoples Caucus negotiator for Article 6, reiterated the concerns and objection of carbon markets. Article 6 of the Paris Agreement establishes a market solution to address climate change through the buying and selling of mitigation outcomes. Indigenous Peoples and other climate activists and lawyers argue that this market mechanism allows polluters to buy offsets rather than truly mitigate their emissions. Ohorella stands for the Caucus’s positions but also recognized the clear dismissal of Indigenous voices, saying that another one of their core efforts is ensuring the “free, prior, and informed consent” from the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is upheld. Due to the finance nature of this year’s COP, Article 6 is a major focus and its quick adoption has brought up several concerns on its integrity.

Ohorella continued to mention how although there is a rightful hesitancy among Indigenous Peoples on engagement with carbon markets, learning about it is essential as it can be leveraged as a tool for sovereignty. He referenced the ways in which the Yurok Tribe used California’s carbon offsets program to buy their land back.

At the pavilion, I had a conversation with Tom Goldtooth, the executive director of the Indigenous Environmental Network. He’s attended all COPs, except for the ones he’s been banned at due to his organizing efforts and criticism of the UNFCCC and carbon trading. He pointed out at how activists like him are censored while the number of fossil fuel lobbyists grow every year. In the UNFCCC, every comma, letter, and space carries significant weight. Goldtooth highlighted how Indigenous Peoples organized to ensure the inclusion of the plural “s” in “Indigenous Peoples” as a deliberate effort to remind negotiators, who too often overlook their voices, that they stand as a collective.

At a press conference with Earthworks, Indigenous Peoples from different social cultural regions from the Amazon to the Artic gathered to present principles and protocols for a true just transition. Many recounted the ways in which “Just Transition” projects essentially became landgrabs by corporations backed by the state and military. “All these big geopolitical power wars between China and the US and Mexico, are felt back home by Indigenous Peoples,” said Nicole Yanes in reference to the Plan de Sonora. She also noted that at the summit to prepare the principles and protocols, many Indigenous Peoples found similarities and in fact are facing the same companies, tactics, and strategies that violate their rights. Again, they reiterated the importance of the “free, prior, and informed consent” of Indigenous Peoples as being core to having a Just Transition. In other words, their rights are not optional and lives are not disposable. Janene Yazzie, ended the press conference, calling not for a just transition, but a just transformation.

I also attended a discussion on the criminalization of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. The speakers presented a map highlighting where earth defenders are killed, with Latin America being the deadliest. Colombia and Brazil were the highest, but the Congo and Philippines were also amongst the top.

Juan Carlos Jintiach, a shuar leader from the Ecuadorian Amazon and Nobel Peace Prize nominee, stated, “We are threats, threats to the global system, and that’s why we’re being killed.” Other speakers also drew connections between state and corporate violence, especially in the context of mineral extraction for the “just transition.” Another speaker emphasized: “We are not against the just transition, as some portray us. What we demand is self-determination; free, prior, and informed consent; and the dignity of Indigenous Peoples to be respected.

As I was heading out for the day, I noticed a large crowd gathered at the Global Center on Adaptation pavilion. I decided to stop and see what was happening not realizing that the people were there for the catered reception. While four women were being honored for their locally led adaptation efforts, the vast majority of people in the crowd were on their phones waiting for the reception to follow. Among one of the speakers was Lastiana Yuliandari, the founder of Aliet Green, a women-owned enterprise based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia focused on empowering local farmers through regenerative organic agriculture and the promotion of fair trade practices. I was captivated by her work and spoke to her following the event.

She shared her story, explaining how following her undergraduate studies — “just like you right-now,” she said — she initially worked for NGOs, a path she was encouraged to follow. However, she grew frustrated with the way these organizations would move from one project to another without any meaningful sustainable work being implemented, often being led by outsiders to the communities. Instead of continuing, she found her own path, returned to her community, and empowered women, who do the brunt of the farming labor in her hometown.

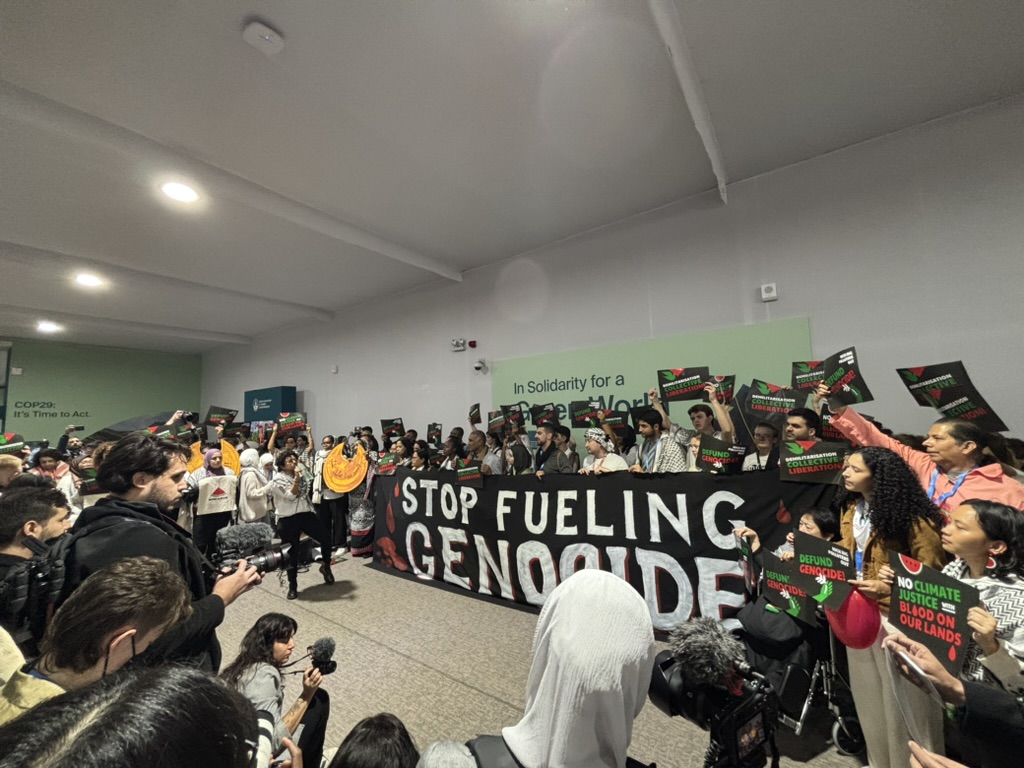

Activists, from lawyers to youth, continued to protest at this year’s COP, representing voices from across the globe. While it was inspiring to witness, I noticed how thousands of people simply walked by the protests without a glance and even scolded demonstrators with an unwillingness to listen. At finance and investment-focused events I attended, speakers often emphasized the need of including voices of the Global South, farmers, and Indigenous Peoples so they’re “not just the ones protesting.” I found this contradictory, as many of the protestors were the same people leading critical discussions in panels and engaging directly with stakeholders.

Ojibwe Elder Great Grandmother Mary Lyons, for example, actively participated in protests and also moderated a session with high-level officials like Senior Advisor to the President John Podesta and Acting Deputy Administrator of the EPA Jane Nishida. Similarly, members of the Palestinian youth delegation, who I saw speak at multiple panels and negotiations, also met with Antonio Guterres and the Green Climate Fund. Other activists also made a heavy presence in negotiation rooms as observers, diligently taking notes. The voices of the Global South, farmers, and Indigenous Peoples are here and have been here making themselves heard through negotiations, high-profile panels, and protests.

It seemed like these protests were dismissed for their disruptions rather than being understood for their intent—to challenge the norms that have driven record fossil fuel emissions, granted lobbyists disproportionate influence, caused record-breaking temperatures, and perpetuated human rights abuses. Disruption of the status quo that the UNFCCC and COP has upheld is the intention.

This brought me back to something else that Tom Goldtooth shared at a panel: “They will divide us [(Indigenous Peoples and the Global South)]—by bringing the ‘good Indian’ to the table, rather than those who will demand the systemic changes and serious conversations we truly need.”

The protestor’s demands were clear: guaranteeing public finance, reducing the private sector’s dominance; stopping genocide and ecocide; ensuring free, prior, and informed consent; and securing $5 trillion for the NCQG.

As Guterres said, “Time is not one our side,” and the lack of action I witnessed during week one was deeply concerning. However, there is so much happening on the ground, led by frontline communities. COP29, just like all past and future COPs, cannot afford to be a failure. The growing number of officials, such as Swat alumnae, fellow Soc/Anth major, and former UNFCCC Executive Secretary Christiana Figueres—chief negotiator of the Paris Agreement—critiquing COP for enabling human rights abusers and petrostates is a hopeful sign. It shows that people are noticing the contradictions and flaws of the systems they themselves are part of.

While Indigenous Peoples, the Global South, and other vulnerable communities have long understood these issues, more people are finally waking up. The urgency for ambition and meaningful action has never been greater.