By: Olivia Fey ’23 (she/her) & Anna Considine ’23 (she/her)

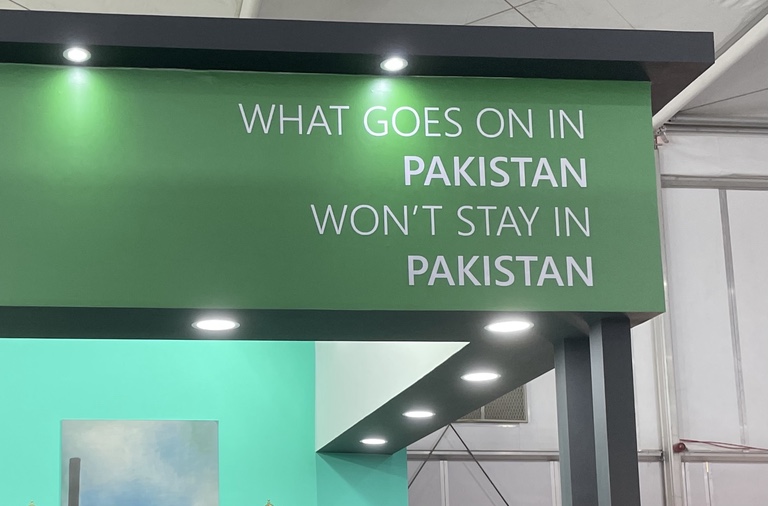

For the past couple of years, the UN has officially sanctioned an event called the People’s Plenary: a moment for civil society groups to take the main stage at COP and make their voices heard. Despite its importance, this crucial event was nowhere to be found on the official schedule for COP27. By complete accident, Professor Ayse Kaya walked into the Plenary on Thursday. On stage were representatives of Indigenous peoples, trade unions, environmental NGOs, the women and gender constituency, the disability rights movement, and youth. She sent our delegation a text, and we all immediately rushed off to witness this powerful moment.

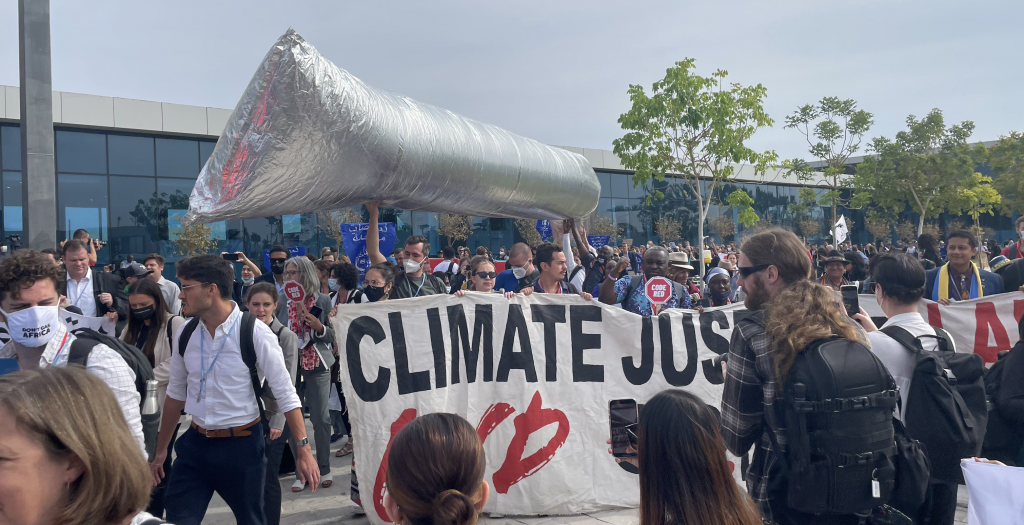

The People’s Plenary, and the ensuing protest, was by far the most impactful moment of our time at COP so far, moving all of us to the brink of tears. The speeches at the People’s Plenary highlighted the lack of hope and real solutions found in UN deliberation halls. The representatives instead called for real climate solutions that resist colonial, capitalist, patriarchal and ableist structures. Each representative ended their speech by saying the same powerful words of solidarity and strength: “we are not yet defeated and we will never be defeated.”

“Reconnecting to your culture is climate action and climate justice.” ~ Jacob Crane

During the speeches, fists rose in the air and people stood up and sang in the otherwise formal, sterile halls of the UN. These moments were made especially powerful in the context of the suppression of activism at COP27. A letter was read out during the People’s Plenary from the mother of the Egyptian activist Alaa Abd el-Fattah, whose imprisonment and hunger strike made headlines at the start of COP. The plenary called for his, and all political prisoners’ release.

While protests at COP27 are meant to be restrained to officially sanctioned events of about a dozen people confined to small platforms, at the end of the session, the crowd marched through the halls of the UN calling for climate justice now. Unified in song with people around the world, we could feel the power, the energy, and the hope that had been lacking throughout the rest of our experience at COP. The protest culminated in a powerful reading of the People’s Declaration for Climate Justice. We ask that you read through this document built out of solidarity between peoples around the world. More importantly, as the representative of the frontline for gender justice asks, “don’t just read our declaration… take action.”

Overwhelmingly, we are left with the feeling that the People’s Plenary is what a plenary at the largest global conference on climate change SHOULD FEEL LIKE. We are currently awaiting the release of the agreements reached at COP27, but we wish to make clear that the real fight, the real solutions, and the place where we must derive our hope comes from the work of the people, not the halls of COP.

We want to use this blog post to share some of the words of the incredible activists that assertively and bravely took the world stage. Their words speak of extreme disappointment with the progress of the UN negotiations, the violences of the climate crisis already affecting their communities, and their belief in the power of people. We would love to share the link so you all can watch it yourself; however, in-keeping with a running theme of lack of access or transparency at COP27, we cannot find a recording of the event so far.

These are the messages of the people:

From All:

We are not defeated, and we will never be defeated.

From the Representative of Indigenous Peoples:

“Without [Indigenous] leadership, even a nature-based solution becomes another false solution.”

“We demand direct access to resources that uplift our solutions, distinct life ways, worldviews, and Indigenous sciences. Our battles do not begin or end here at COP. When we return to our respective homes, we will continue the real work on the ground. We must pick up the work where states fall short. Supporting the self-determination of Indigenous peoples is the best for all peoples and [the] planet.”

“There is no climate justice without the rights of Indigenous peoples.”

From the Representative of the Frontline Struggle for Indigenous Peoples:

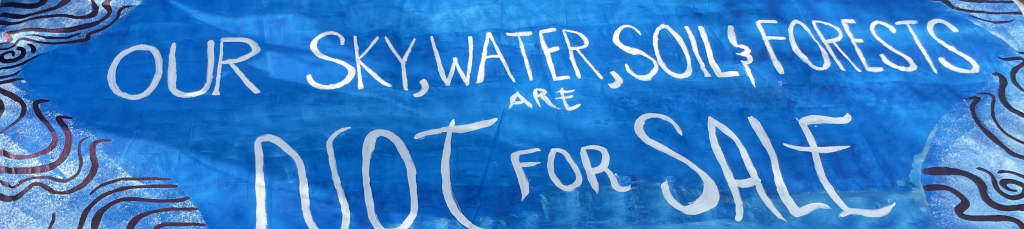

“Carbon offsets, net zero, and nature based solutions are a new form of colonization that further threaten our communities. These are false solutions.”

“It will be Indigenous and frontline communities that will bring forth the solutions that are needed.”

From the Representative of the Women & Gender Constituency:

“They may have drawn imaginary borders to divide us [and] color to segregate us, but they will not be able to break the collective power of our voices.”

“The chains of oppression must be broken.”

“We will not support your predatory economic system for greed and opulence.”

“We will rise like the water. We will stand strong as mountains. Our voices will be lifted by the wind. Our collective power will burn as brightly as fire.”

From the Representative of the Frontline for Gender Justice:

“We may sound loud in this room, yet we are not a part of any decision making.”

“Despite all these beautiful speeches on gender on gender day, gender is still not on the agenda. We are still not a priority.”

“When we ask for climate justice, do you think we are beggars asking for pity? Do you think that we want more loans and debt? Do you think that local communities do not have local solutions?”

From the Representative of Trade Union NGOs:

“[We] are paying a high price for lack of decisive leadership on climate action. […] We demand more.”

“We say no more. We urgently need a just transition. We ask for mitigation and adaptation, loss and damage mechanisms, all debts paid in the Global South. Just transition needs workers at the table. Others should not decide about our future. Labor rights are human rights.”

From the Representative of the Frontline Struggle for Workers’ Rights:

“We want to […] be independent, to be able to move forward as the working class of Africa, the Global South. We are not victims or beggars. We are demanding what is ours.”

“This is a class on whose back renewable technologies and the future for a green life are being based on. This is a class that may never have access to renewable energy, a class that will never have dignified work and will continue to be under the dark mines of Africa. […] As trade unions, we are here to warn and to caution that we must not repeat the history of the mining sector of our continent.”

“We demand to participate in a formal social engagement framework.”

From the Representative(s) of Environmental NGOs:

Speaker 1:

“We endorse this declaration. We do so because our people are suffering across the world. Their suffering and their vulnerability to climate change is caused by the structural injustices of economic and political systems.”

Speaker 2:

“We should not be surprised that for two weeks, those leaders of rich countries have been saying they believe in science, saying they believe in [the] 1.5[°C global warming limit], that they care. We are absolutely sick of their empty words – hypocritical words – and outright lies.”

“We have always known one truth: that this fight will never be won in the negotiating halls. It will only be won by the power of our movement […]. They treat the lives of our sisters and brothers as disposable. For us, they are non-negotiable.”

“We stand in defense of the 1.5 [limit], beyond which will be a death warrant for millions of people across the world. We believe as people we need to stand in solidarity to build a future of peace and justice. We believe it is only through the power of people that we can build a better world for all. We are unstoppable.”

“THE ONE THING THEY FEAR THE MOST IS SOLIDARITY.”

From the Representative of the Struggle for Youth Justice:

“How do we find hope when our current and future world is on fire? […] We practice hope every day because we don’t have an alternative.”

“Every thought and action has a collective impact. Collective drops create rivers, and rivers carve canyons. We can change the world.”

From the Representative of the Frontline Struggle for Climate Justice:

“We cannot continue going forth without looking at what brought us here today. We blame [climate change] on colonialism, on patriarchy. These systems must be changed […] before we can start talking about climate change.”

From the Representative of the Frontline Struggle for Environmental & Racial Justice:

“We have to repair our ecology and we have to repair our relationships with each other. We have to love each other.”

“We have nothing to lose but our chains.”

From the Representative of the Disabled Rights Movement:

“I will be brief in my statement, but not as brief as [the mention of] disabled people in the Paris Agreement.”

“Like climate change, disabled people have been left behind.”

“No human rights without disability rights. There is no climate justice without disability justice. Nothing about us, without us.”

From the Representative of the Frontline Struggle for Disability Rights:

“When I left the safety of home, I realized my colonization had affected my ability to recognize that I was not the problem, but the systems were.”

From the Family of Egyptian Activist Alaa Abd el-Fattah:

“Show us every day what courage and determination look like.”

“[There is a] shared pain of those who believe in a better world.”

“You told us we are your family; our pain is your pain. You made no empty promises. You simply told us that we stand with you.”

“Everyday, we survive. We matter, just like every tenth of a degree matters.”

“Together we can break the walls of fear. Our horizon is freedom for all.”

Chants Filling the Plenary:

“The people, united, will never be defeated!” / “El pueblo, unido, jamas sera vencido!”

“Free Alaa; free them all.”

“Solidarity forever.”

“Power to the people.”

“When the world that we know is under attack, what do we do? Stand up, fight back.”

“We are the people / The mighty, mighty people / Fighting for justice / And for liberation / Everywhere we go / The people ought to know / Who we are / Who we are / So, we tell them / …” (repeat)

Thank you enormously for taking the time to read the voice of the people.

Signing off,

Olivia & Anna <3

Please note: we transcribed these quotes during the Plenary to the best of our ability, but they may not be perfect as a result. In any case, we hope to have accurately captured the sentiments of these powerful activists.

Additional resources: