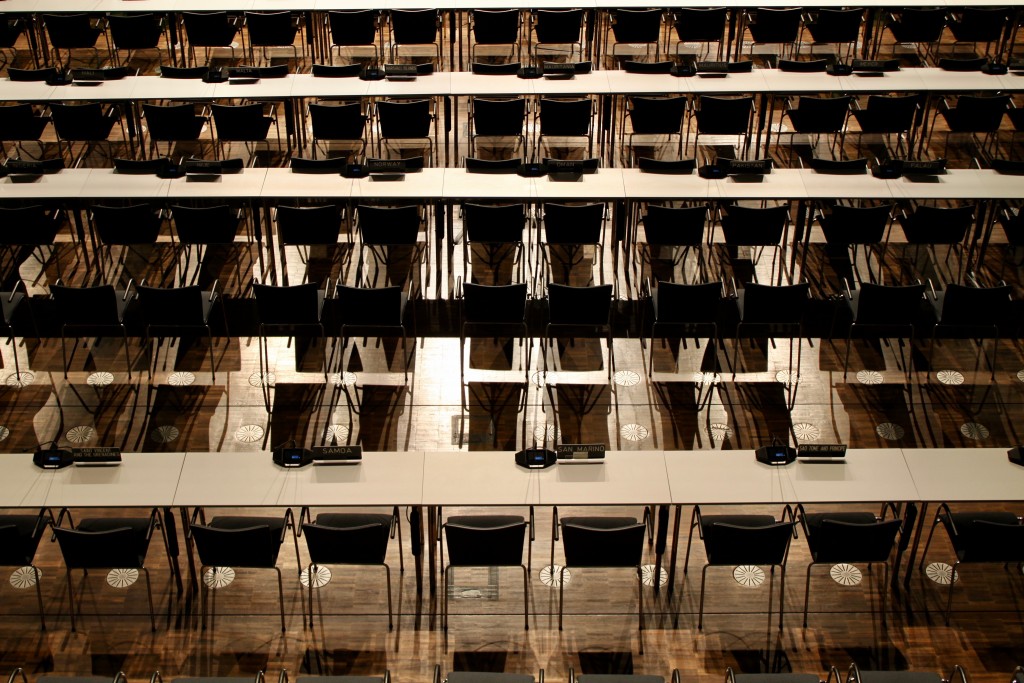

The third day of COP23 was packed to the brim with dozens of informal negotiations, party roundtables, and side events hosted by some of the many non-party stakeholders attending the conference. This COP has about 19,000 attendees, including more than 11,300 party delegates and about 6,000 non-party stakeholders, and there are complicated rules about which events are open to which participants.

According to someone I talked to who had been to many previous COPs, almost all negotiations (except for the most informal discussions) used to be open to anyone with access to the conference. As the size of the conference has grown, the negotiations have become more intense, and information is more quickly distributed, the parties have become more hesitant to allow non-party stakeholder observers into negotiations. At the same time, many of these stakeholders have cultivated personal relationships with career diplomats who attend many consecutive COPs, and so while more meetings are now technically closed, exceptions are often made on the request of party delegates.

Countering the trend of increasingly limited access and ability to influence negotiations directly, the Fiji Presidency has made it a point to engage non-party stakeholders in productive dialogue. The highlight of this approach was the Open Dialogue, a discussion that took place this morning with several dozen party delegates and representatives from the nine non-party constituencies. Two of the most relevant of these constituencies are YOUNGOs (YOUth NGOs) and RINGOs (Research and Independent NGOs); Aaron, Jennifer and I have been attending their daily meetings. During the Open Dialogue, delegates from both parties and non-parties agreed that connections between civil society and government, both domestically and during climate negotiations, were critical to enhancing the ambitions of the Parish Agreement. That being said, despite being labeled a dialogue, the meeting could have been more aptly described as Stakeholders Reading From Written Statements, and little to no substantive outcomes were reached. Clearly, more dialogues are needed.

In addition to the Open Dialogue, NGO constituencies get a brief amount of time to speak in what is called an intervention at specific negotiating meetings called open plenaries. One of the highlights of my week so far was frantically editing an intervention about climate finance for YOUNGO in the back of an open plenary meeting, minutes before our representative read it to the parties and observers at the meeting.

Beyond formal interactions between parties and non-party stakeholders, many climate action organizations are engaged in a massive effort to lobby delegates, shame uncooperative parties, and shape the topics of discussion. With the help of the Swarthmore hub of the Sunrise movement (shout-out to Aru), I have recently become a member of the Climate Action Network, a network of climate action organizations that work together to influence the negotiations and push a progressive climate agenda. As a result, I have seen some of the incredible behind-the-scenes work that goes into maintaining a coherent and consistent climate action campaign. For example, the Climate Action Network organizes a daily event at 6pm titled “Fossil of the Day,” in which a theatrical man dressed in a skeleton sarcastically presents an award to the party that has acted poorly or stalled negotiations. While very silly, shaming countries into behaving more constructively is important, especially when one party can hold up progress on any agenda item.

In the end, the Paris Agreement can be signed only by parties, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are determined by national governments, and the COP by definition designates the Conference to be “of Parties.” But even in the short time we have been here, it is clear that non-party stakeholders have a serious role to play in framing the conversation and applying pressure with the goal of concrete and ambitious climate action.