Before the semester is out, we want to take a moment to remember Prof. Thompson Bradley, a passionate and gifted teacher and activist for peace and justice at Swarthmore College, the local region, and the world.

President Val Smith informed the Swarthmore community of Prof. Thompson’s passing on October 3, and the Communications Office provided a rich remembrance of his life, work, and activism. We reprint that below, along with a poem honoring Prof. Thompson by Swarthmore alum Bill Ehrhart that appears on the Veterans for Peace website.

Dear Friends,

With deep sadness, I write to share the news that Professor Emeritus of Russian Thompson Bradley died peacefully Sunday, Sept. 22, at his home in Rose Valley, Pa., after a long illness. Tom is remembered for his deep and abiding love of Russian language and literature, his commitment to generations of students, and his devotion to decency and justice in all of his pursuits. He was 85.

Tom is survived by Anne, his wife of more than 60 years, their three daughters, and two grandchildren. A celebration of his life will be held at 3 p.m. on Saturday, Dec. 21. in Upper Tarble in Clothier Memorial Hall.

I invite you to read more below about Tom, his remarkable life, and his innumerable contributions to our community.

Sincerely,

Valerie Smith

President

In Honor of Professor Emeritus of Russian Thompson Bradley

The Swarthmore community has lost one of its most influential and beloved faculty members, Professor Emeritus of Russian Thompson Bradley, whose teaching and passionate intellectual engagement with Russian language and literature were inseparable from his lifelong commitment to and advocacy for peace and social justice.

“No one in this life is indispensable, but Tom came awfully close,” says longtime friend and colleague John Hassett, the Susan W. Lippincott Professor Emeritus of Modern and Classical Languages. “He was a born teacher, completely dedicated to his students. His preferred space was always the classroom.”

“I recall Tom’s gift for making his interlocutor feel heard and appreciated,” says Professor of Russian Sibelan Forrester. “His face would light up in a very affirming way when he heard a good idea or an interesting story.”

Tom was born in New Haven, Conn., and raised not far from there on a farm in Cheshire. His love of languages first took hold at the Hotchkiss School, where he studied French and Latin. In his senior year, he was introduced to Russian, an encounter that ignited his love of the language and its literature. At Yale University, where Tom earned a B.A. in Russian, and later, at Columbia University, where he pursued graduate work in Slavic languages and literatures, this love deepened and took on literary and historical dimension.

Tom’s recognition of the complex dialectical nature of the relationships between Russia’s language and literature and its revolutionary history inspired his impassioned intellectual and social commitments and was the vital current that found expression in all that he did as a teacher, activist, colleague, and friend.

In 1956, Tom married Anne Cushman Noble. That same year, a few months after graduating from Yale, Tom was drafted into the U.S. Army. In keeping with his moral convictions, he made the principled decision to enlist rather than seek a deferment, then afforded to students continuing on to graduate school. He served for two years at an American base in Germany, where he had been recruited for military intelligence for his language skills.

After completing his service and returning to the U.S., Tom resumed his academic career at Columbia. He then spent a year in Moscow as one of 35 American scholars on a cultural exchange. While working in the Lenin Library and the Gorky Institute of World Literature, Tom witnessed the gradual shift from the Stalinist regime to that under Nikita Khrushchev. He also met with and befriended members of the Soviet dissident movement, whose courage he greatly admired. Years later he invited one of them, well-known human rights activist Elena Bonner, to speak on campus.

After teaching briefly at New York University, Tom joined Swarthmore’s faculty in 1962 as an instructor in Russian. Here, he connected with an earlier generation of scholars, especially those in the Modern Language and Literatures (MLL) Department, who had been displaced by World War II and other major conflicts and had immigrated to the U.S.

In Russian, he notably joined, among others, section head Olga Lang, the quintessential intelligentka and a fount of poetry who had worked with major figures in the Communist Party, and Helen Shatagina, who had been born to an aristocratic St. Petersburg family but politically, Tom said, was an anarchist.

“It was a rich culture and wonderful, cosmopolitan world they brought with them,” he once said. “At Swarthmore, we were the fortunate beneficiaries.”

At the College, Tom also found students whom he described as having a “real commitment” to living the intellectual life. His Russian novel class became legendary, invariably drawing the most students of any MLL course at the time.

In their reflections and testimonials, colleagues recognize Tom’s gifts and dedication as a teacher, as well as his capacity to communicate the beauty and power of literature to broaden and deepen the scope of our moral imagination.

Marion Faber, the Scheuer Family Professor Emerita of Humanities and Professor Emerita of German, says she was “astonished to learn that Tom regularly met individually with every one of his students both before and after each assigned paper—a uniquely generous investment of time and a sign of his devotion as a teacher.”

“More than anyone else I knew here at the College,” says Professor of German Hansjakob Werlen, “Tom’s love of literature always came through in his superb teaching, as did his ability to convey the essence of what literature’s particular aesthetic form can do: free up the imagination for the ways other people live and lived in various places and times and make us empathetic participants in those worlds with all their diverse inhabitants. That empathy extended to everyone living in this world.”

“Tom’s grasp of literature was profound, and profoundly moving,” writes Philip Weinstein, the Alexander Griswold Cummins Professor Emeritus of English Literature. “I never knew anyone so passionate about his beliefs who nevertheless refused steadfastly to demonize others whose views he rejected. He didn’t speak much about love—at least not in my hearing—but his whole embodied stance radiated love. Political passion is common enough, but its being humanized and enlarged by love is passing rare. I know of no one else who embodied both these realities so well.”

Tom received tenure in 1968 and chaired MLL for several years. Throughout his career, he never separated his teaching from his social and political activism. Tom spoke of this when he retired in 2001: “I think there are fewer and fewer people in academia today who think of their lives as having to do with a practice outside of academia. I can’t imagine only doing activism, or only teaching. To me they seem as indivisible as literature and history.”

Tom embodied this understanding in his teaching and his activism—both on campus and off—and was at the forefront of efforts to extend the reach of the College curriculum to the larger community.

“Tom was devoted, personally and politically, to decency and justice, and virtually everything he did reflected those commitments,” says Professor Emeritus of Philosophy Rich Schuldenfrei, a longtime colleague and friend. “He was politically active on the left for his whole adult life [and] a leader in mobilizing the College against the war in Vietnam. He mentored conscientious objectors and arranged for training for the faculty to do so. He was active for many years with Veterans for Peace.”

Before opportunities and support for connecting the curriculum to the community were common, Tom forged that path in his own teaching. As Professor Faber notes: “He not only brought contemporary poets like the Vietnam War veteran W.D. Ehrhart ’73 to the College but also taught literature classes in prisons.”

Adds Hugh Lacey, the Scheuer Family Professor Emeritus of Philosophy: “He was always there when it mattered—speaking, organizing, and teaching countless students outside of the formal classroom setting and inspiring them to think and act in new ways.”

Professor Lacey credits Tom with generously participating in, and often leading, many of the activities that made Swarthmore College “live up to its claim to be a community.” Those efforts included organizing a full day of talks and activities to celebrate the first Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day; engaging in the Faculty Seminar on Central America in the 1980s to educate the general public about the wars and U.S. foreign policy in the region; supporting the Sanctuary Movement for refugees from those wars; developing a faculty exchange program with a university in El Salvador; and, in the 1990s, helping to create and sustain the Chester-Swarthmore College Community Coalition, which planned educational and other collaborative programming and opportunities for students from Swarthmore and Delaware County Community Colleges and residents of Chester, Pa.

After he retired in 2001, Tom became what one alumnus describes as a “foundation stone” of the College’s Learning for Life program (LLS). Three years later, colleagues and former students published Towards a Classless Society: Studies in Literature, History, and Politics in his honor. Counting his additional years of teaching Russian literature to legions of devoted alumni in New York and Philadelphia through LLS, Tom’s Swarthmore teaching legacy extended nearly 50 years.

Tom was always generous with his time and knowledge. In a 2014 interview, he provided a powerful perspective, unheard until that time, on the division among faculty members during the 1969 Admissions Office takeover.

Tom once said of his European colleagues, several of whom he counted as teachers (and “luckily” as friends): “I always felt, when one of them died, as if more than a person or colleague had gone, but a whole world.” It is not a stretch to say that Tom’s death has left a similar void.

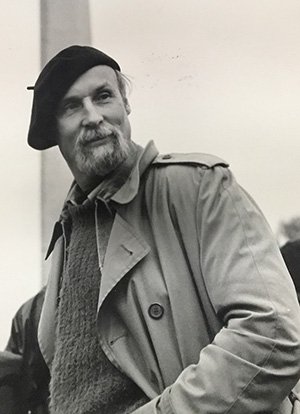

“I’ll always remember him as a loving man, a convivial host at his home, encircled by his beautiful family,” Professor Faber says. “And I’ll always remember him as a man of great élan, in his long black winter overcoat, beret and red scarf, striding to a classroom or a meeting.”

As Professor Schuldenfrei writes, Tom “leaves behind family, friends, political allies, and colleagues who will miss him and forever think of him as a model of political commitment and integrity, and personal loyalty and love.”

In memory of Thompson Bradley, a poem written by Bill Ehrhart after Tom’s death.

Thompson Bradley

He looked like Lenin. Really.

I’ve never forgotten the first time

I saw him, fifty years ago; I had

to do a double-take, knowing Lenin

had been dead for nearly fifty years.

He’d pace back and forth, gesticulating

to a classroom full of college kids

while rolling a cigarette, explaining

Russian Thought and Literature

in the Quest for Truth.

What Lenin took for truth, I’ve

no idea, but through the years

I came to know that truth meant

justice, peace, honesty and fairness,

decency and generosity to Tom.

You name the issue, Tom was always

on the side you wanted to be on:

wars in Asia, the Americas, the Middle East;

civil rights, prisoners’ rights, women’s rights,

gay rights, the right to live with dignity.

He looked like Lenin, but he lived

a life that Lenin would have envied,

or certainly should have. If Tom had led

the Revolution, I’d have followed him

to hell and back and into heaven.

– W. D. Ehrhart

As a radical Swarthmore professor, Tom developed a friendship with Ehrhart, then a returning Vietnam combat vet who felt like a fish-out-of-water on the Swarthmore campus.